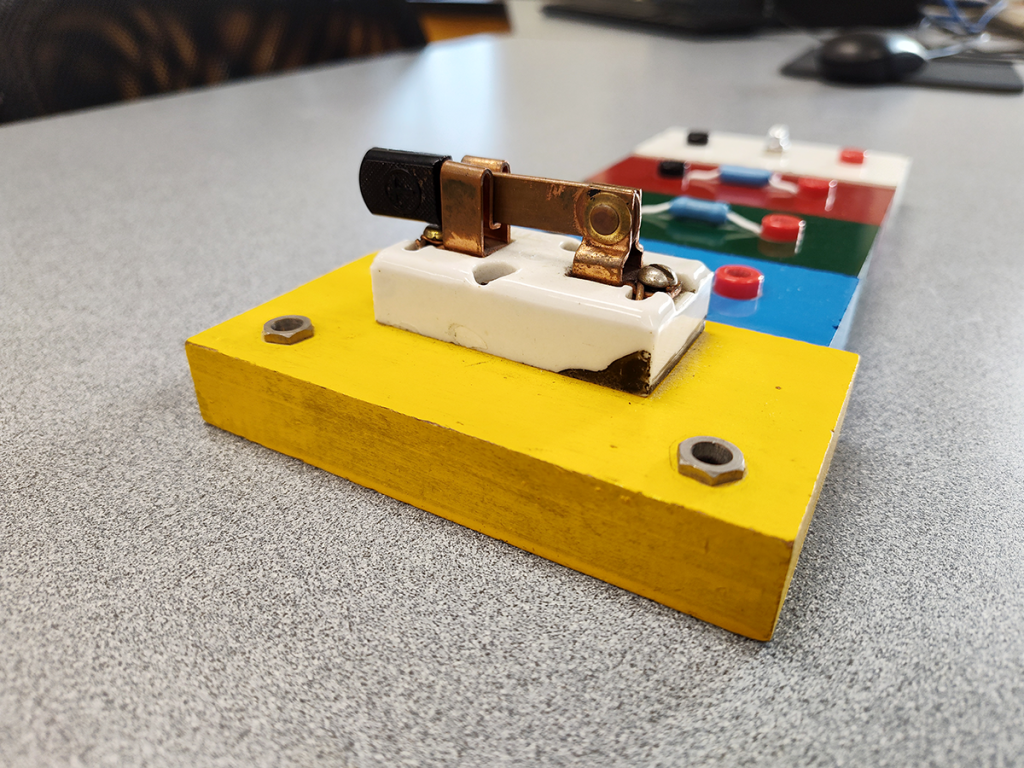

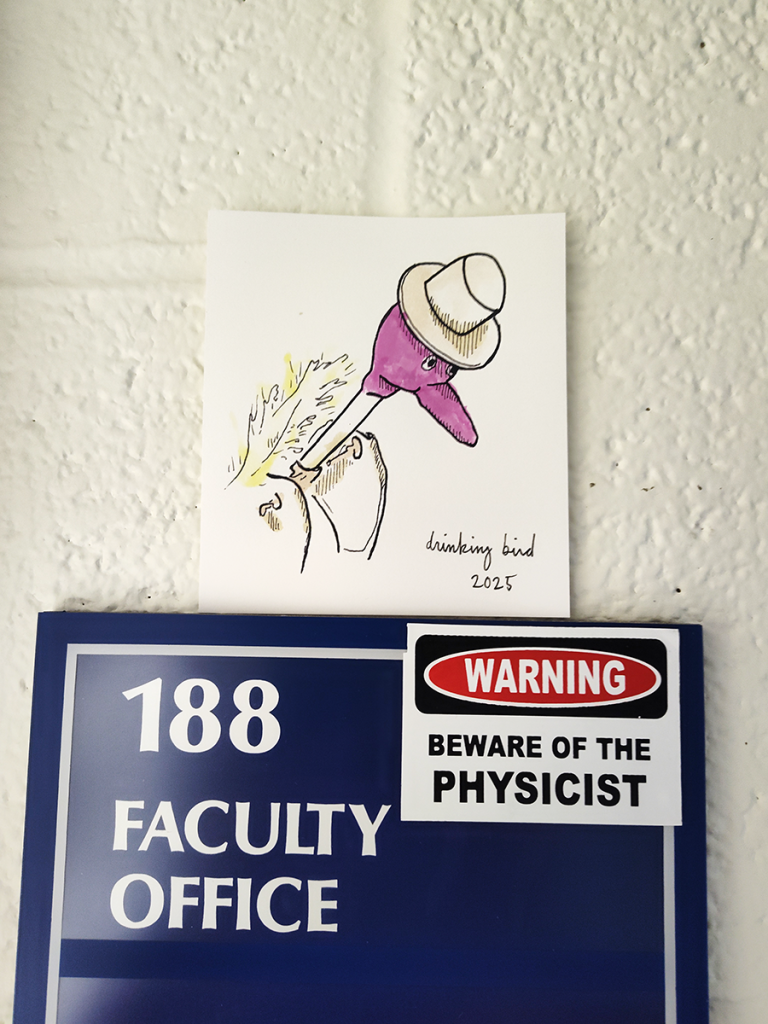

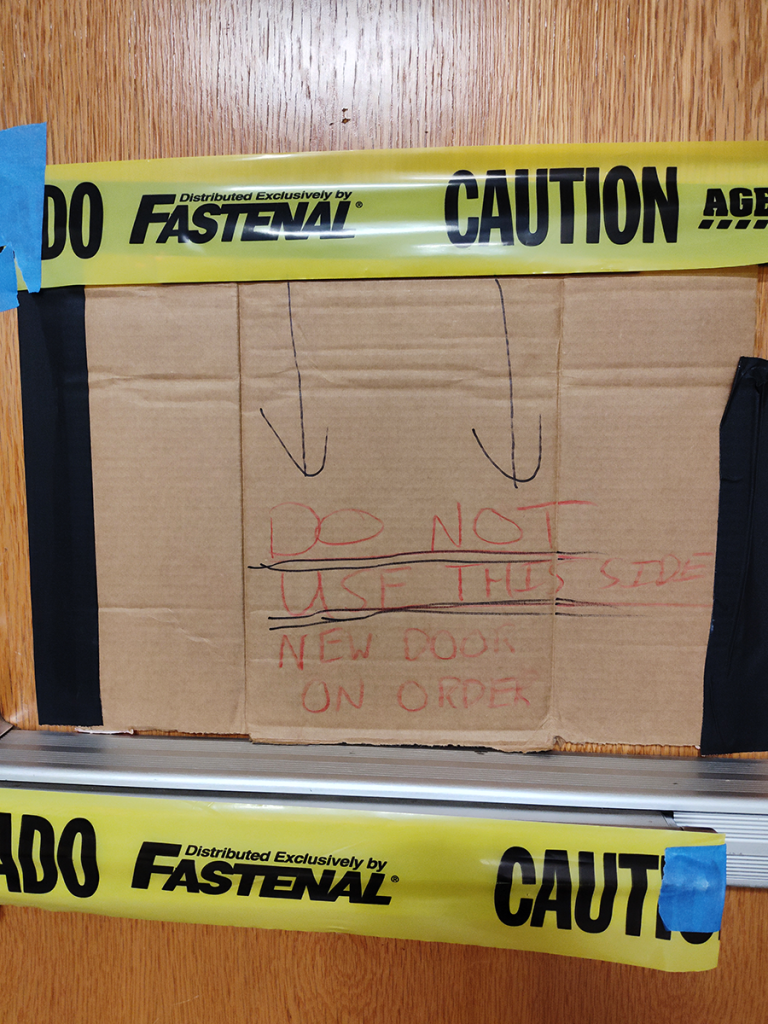

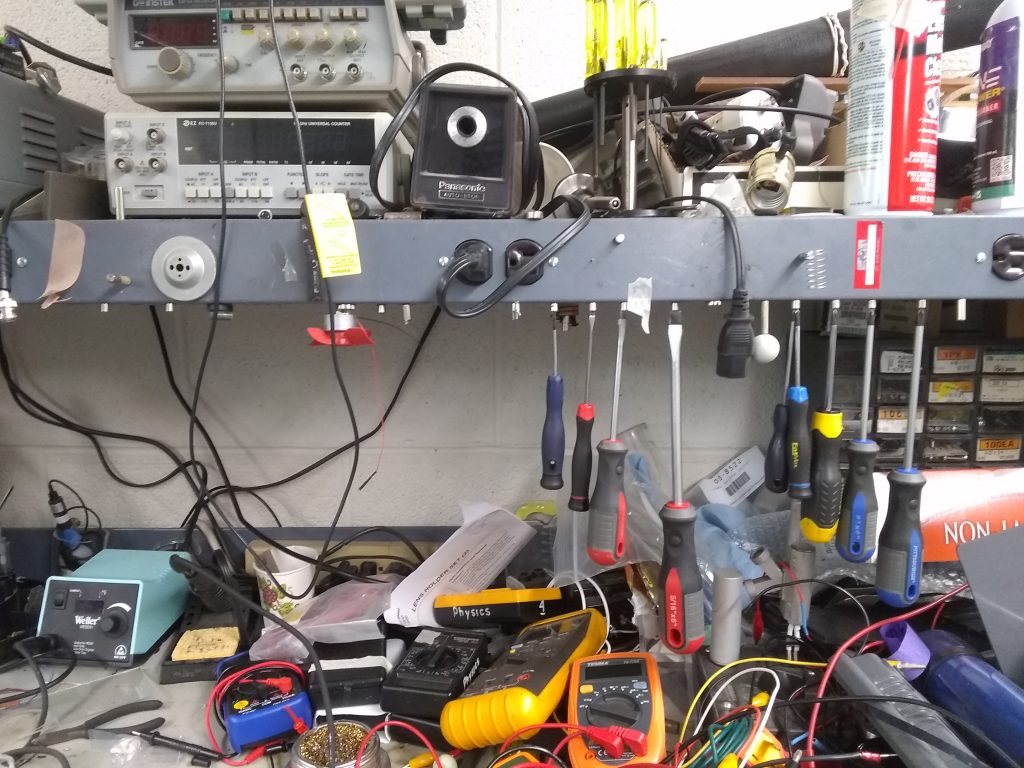

Welcome to Olin Science 181, the Physics & Astronomy department’s machine shop. As the department’s support team, we regularly discover, design, and build all sorts of curiosities. This blog is just a small sample of the fascinating things we come across every day.

They’re interesting. Sometimes strange. Sometimes oddly charming.

Always worth sharing.