We field a lot of requests for small objects in the shop these days. It’s not that there aren’t plenty of big/huge/enormous things worthy of serious research and scholarship (see: stars), but physics sometimes gets wild when you go small. And not even quantum mechanics small… that’s where calling physics not intuitive doesn’t even begin to cover it.

We’re talking channels and structures where 100 microns makes a difference. A micron, or micrometer, is one-thousandth of a millimeter; 100 of them is a tenth of a millimeter. In the general ballpark of the width of a human hair. It’s the scale where you learn the finer points of a tool’s tolerances, where you set a machine to do the work and wait until it’s all finished to figure out if it worked.

Mistakes happen.

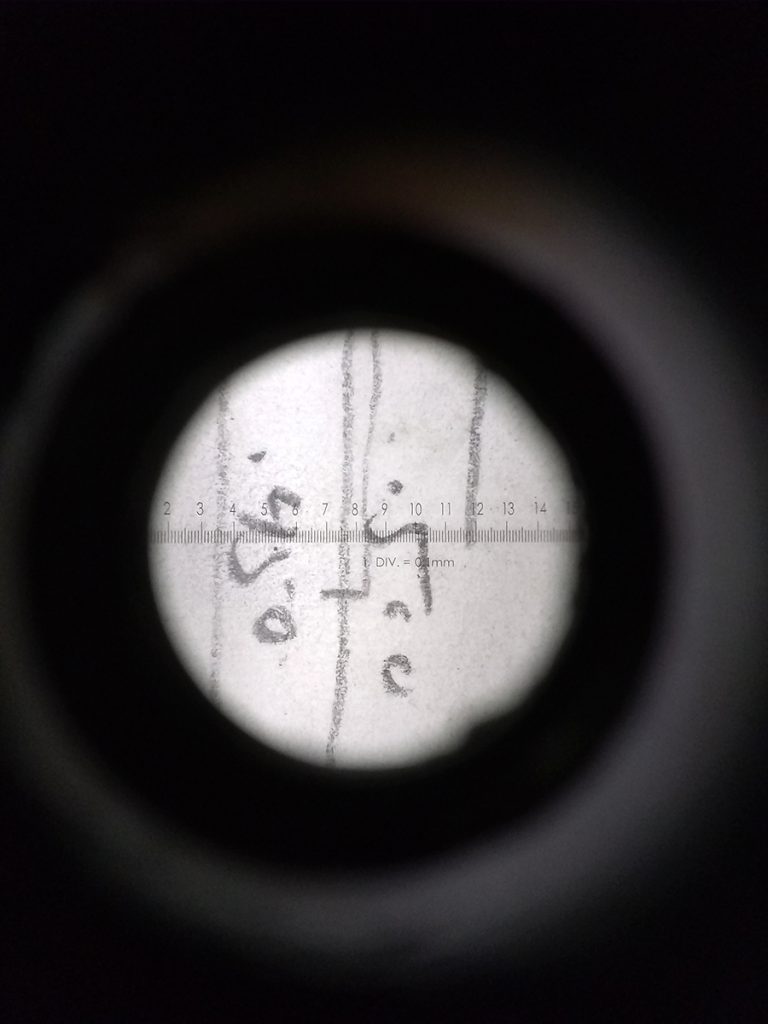

Very tiny things also defy your eyes’ ability to inspect them, so we rely on microscopes and other optical magnifiers to check on the quality of work. One of the handiest is the magnifier shown above, a Bausch + Lomb Hastings Measuring Magnifier. It uses a Hastings triplet lens system, composed of three separate glass lenses bonded into a single, composite lens. Doing so produces crisp, distinct images without distortion. At the end it has a scale, so that we can press it against an object to inspect and actually measure features less than a millimeter across!

One of the best features of this magnifier is its portability. At 7X magnification, it’s less powerful than a microscope, but its case fits in a pocket, so it can go anywhere. Clear plastic sides admit plenty of ambient light, removing the need for additional illumination that a microscope requires. You simply pick it up, inspect your object, and carry on. Confirm that microfluidics channels are the proper width. Ensure that you’ve cleaned all the swarf away from tiny features. Examine tools up close for minor damage to their edges.

Or check out the tiny world all around you, just because you can. Some of the best science starts with noticing something neat, and just digging deeper.