Presented without comment, with the acknowledgment that presenting this at all is a sort of comment.

Discoveries in the Physics & Astronomy shop | Science, curiosities, and surprises

Presented without comment, with the acknowledgment that presenting this at all is a sort of comment.

Behold: a box which counts! That’s it, for the most part. It counts pulses of positive voltage. Very quickly, and you can set some thresholds to tell it to count certain values but not others.

It also gates over an interval you set, so you can tell how many pulses it receives over, say, one second. It counts, displays the total, then counts again. Displays the new number.

We use these for our wave/particle duality lab experiment, which relies on counting individual photons. Yes, those. The teeny, massless quantum packets of energy, the messenger particles of electromagnetism. Light. It acts in non-intuitive ways, and the students who think “that’s amazing and I want more!” sometimes become Physics majors.

Part of using this box – just one aspect – is helping convince those students that only one photon at a time can be reaching the photomultiplier tube sensor. At the speed they move, a mind-boggling number of photons can zip through that meter-long box without bunching up. c in air isn’t all that far from c in a vacuum, so if your one-second counts aren’t remotely near 299,792,458 (adjusted for PMT sensitivity and other losses), you know some of those photons are pretty lonesome. Sometimes you need a little math to make sense of things you can’t directly sense.

One other fun aspect is a little switch hidden on the back: cricket. It’s the volume switch, letting the box emit a little beep for every pulse it counts.

If you’re counting pulses from a radioactive source, which arrive randomly, it can be informative to hear these irregular signals, gated and grouped into numbers which show a decaying curve.

If you’re counting 100,000 photons every second, in a room of other lab benches also counting thousands of photons? Less informative, more irritating.

Sometimes, we have old equipment which is rarely, if ever used. Case in point: the mid-20th-century spectroscopes which have been supplanted by digital spectrometers. They’re both effective tools for examining a spectrum of light, one by eye and the other fed by a USB cable. Using a diffraction grating, they split light into its constituent spectrum – its rainbow, more or less – and can identify the presence of individual wavelengths. Not something our eyes can do, as they blend everything together, though that’s very helpful in most situations, such as reading this on your screen.

Summing bands of reddish, greenish, and bluish into a broad rainbow of colors is one neat-o trick.

With a diffraction grating, reflection grating, or prism, you can refract light out along a range of angles which correspond to its constituent wavelengths. Put a sensor at a known angle – your eye or a semiconductor exhibiting the photoelectric effect – and you know the wavelength if you sense a photon. It’s a simple piece of information which can be used to unlock a staggering amount of interesting, related information about what you’re observing.

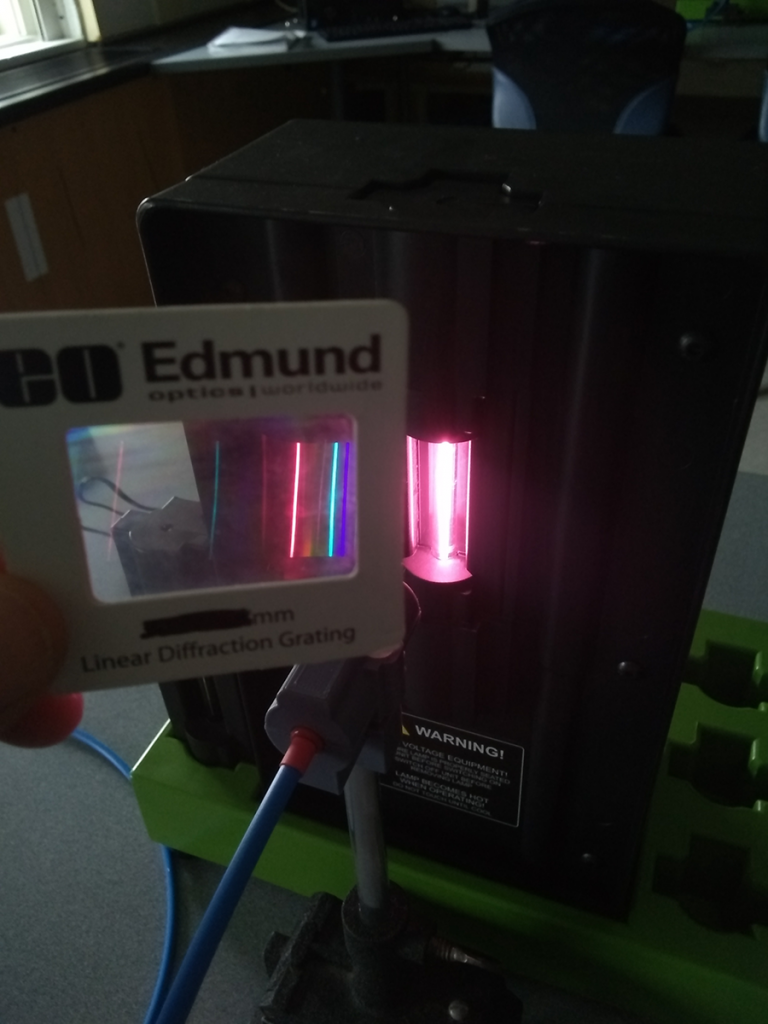

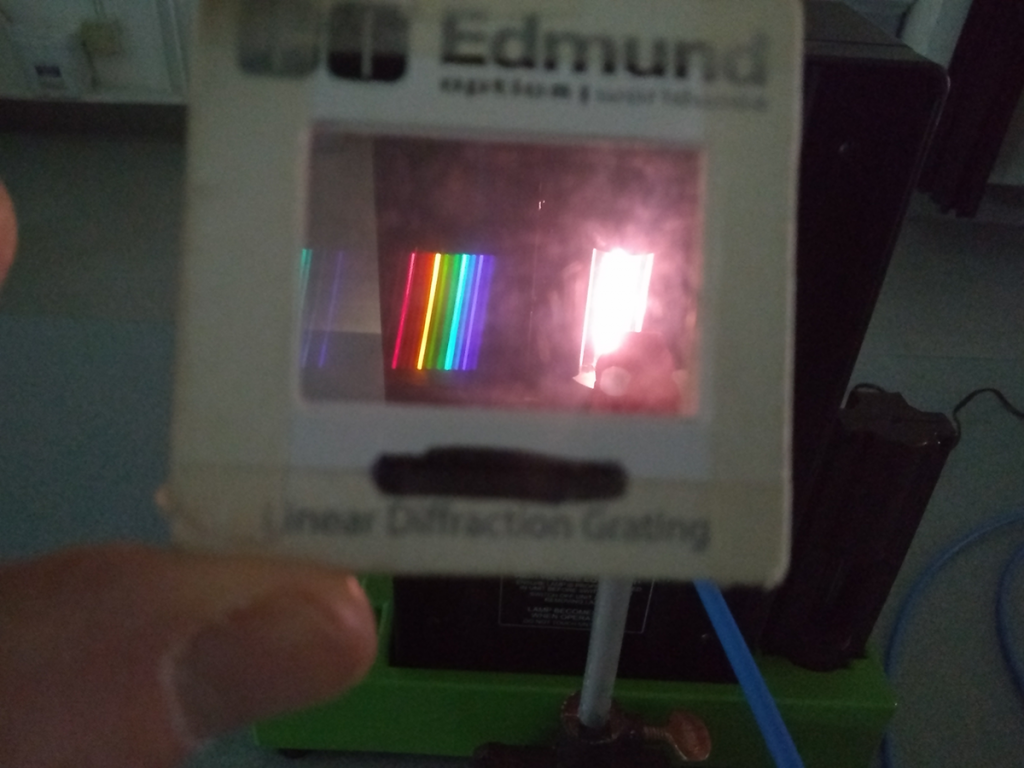

You can also use a diffraction grating to get a quick sense of the entire visible spectrum of a source by holding it off to the side. Remember: the angle of the light’s path change as it refracts, so you’re trying to angle it back to your eye. Hydrogen has a distinctly pinkish-purplish hue when excited at high voltage, and you can see the dominant red and blue lines in its spectrum. With just that one electron to absorb energy and emit photons, the spectrum can only be so complicated.

That’s in contrast to helium, with its two electrons. The spectrum doesn’t look white, per se, but is much more filled out than hydrogen. Look at those spectral lines, and there are so many more! They’re distinct, measurable, and provide a “fingerprint” that can be immensely useful for scientific study. Or for just looking cool.

In our cabinet of meteorites – because everyone has one of those in an odd corner, right? – we have a number of surprisingly-dense space rocks. You can’t really hurt them, considering they’ve already been dropped far harder than any puny human can manage, so occasionally we get to pass them around.

Here we have the Plainview meteorite, from Hale County, Texas. Discovered in 1917, the original find weighed over 400 kg (a lot!), and our little chunk is a mere 184 g. Isn’t it adorable?

Our old iron optics rails get very little use anymore, as we phase them and their accessories out. Most of them, that is.

We may not use the old glass lenses much – sometimes, not often – but the spring-loaded holders still come out from time to time. They grip certain oddly-shaped objects well, and their heavy iron bases do an excellent job of keeping things like fiber optic cables upright and in place.

Rapidly approaching 60 years old, lens holder. April 1963, $6.25. That’s $61.31 in today’s dollars.