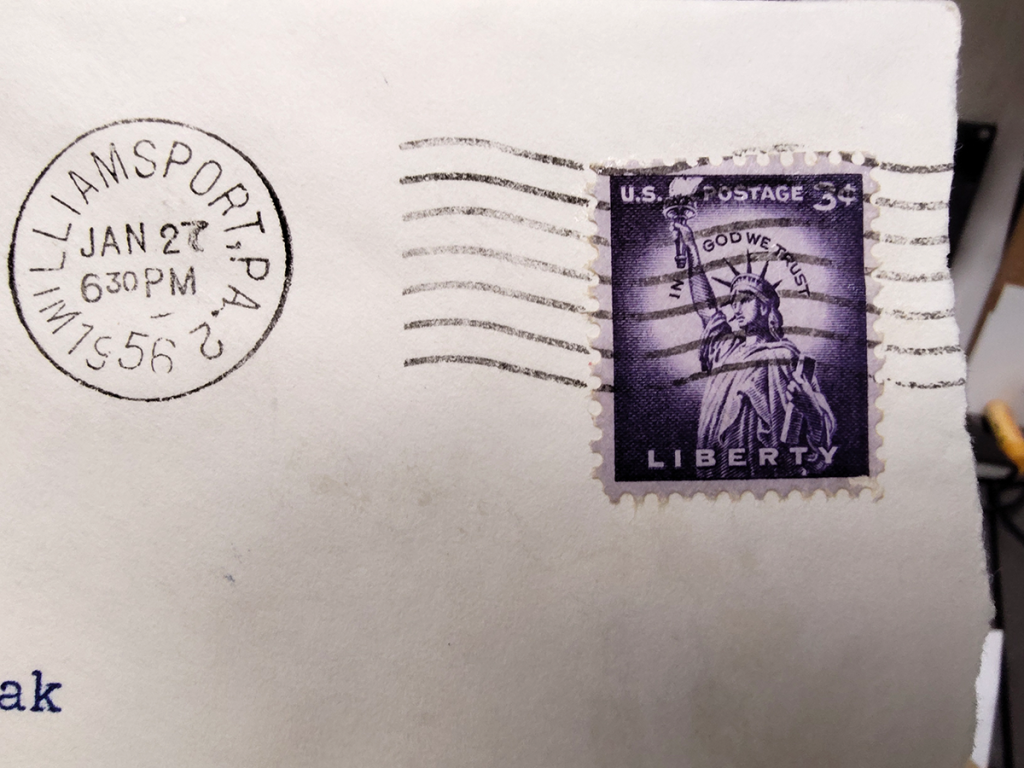

First class postage as of January 27th, 1956 cost three cents.

Discoveries in the Physics & Astronomy shop | Science, curiosities, and surprises

First class postage as of January 27th, 1956 cost three cents.

At one point in time, the slide rule was an essential tool in a physics/math/engineering education. Built and etched with high precision, they enable a skilled user to perform all sorts of mathematical operations with speed and ease. It’s the power of logarithms in a hand-held device.

Which, if you’re the sort of person who can master a slide rule, means you can also fully grasp the particulars of how one works.

It’s a smidge harder to get there with an everyday calculator. The gulf between the solid-state electronics inside one and the button-pressing interface is enormous.

At one point in time, this beast was a handy demonstration device at the front of the lecture hall. Visible from way in the back, it lets an instructor illustrate proper slide rule use to an entire class at once.

Not that that happens much anymore, but this thing is awesome. If you found one back in the closet, you’d keep it handy, too.

Why, yes, astute observer: that is a can, formerly home to Maxwell House BOLD French Roast coffee, now filled to the brim with #2-64 fine thread, slotted-head screws. No, it was not labeled.

A substantial quantity of an infrequently-used fastener around here. One can infer that we have spares enough to last quite some time.

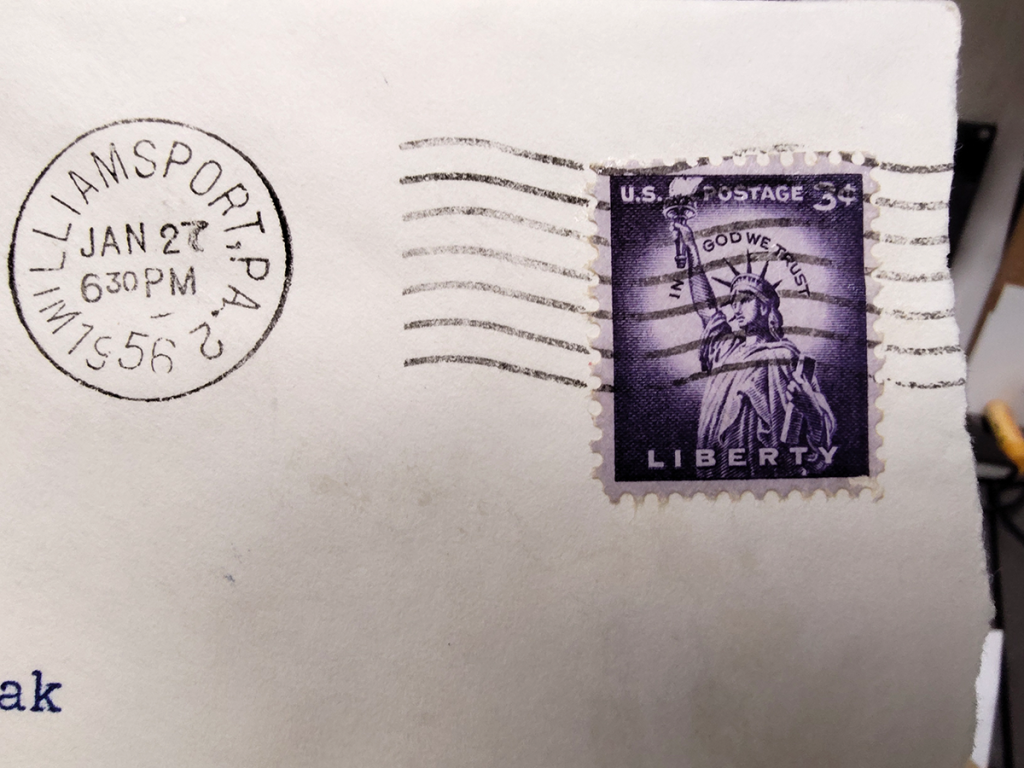

“Connerctor!”

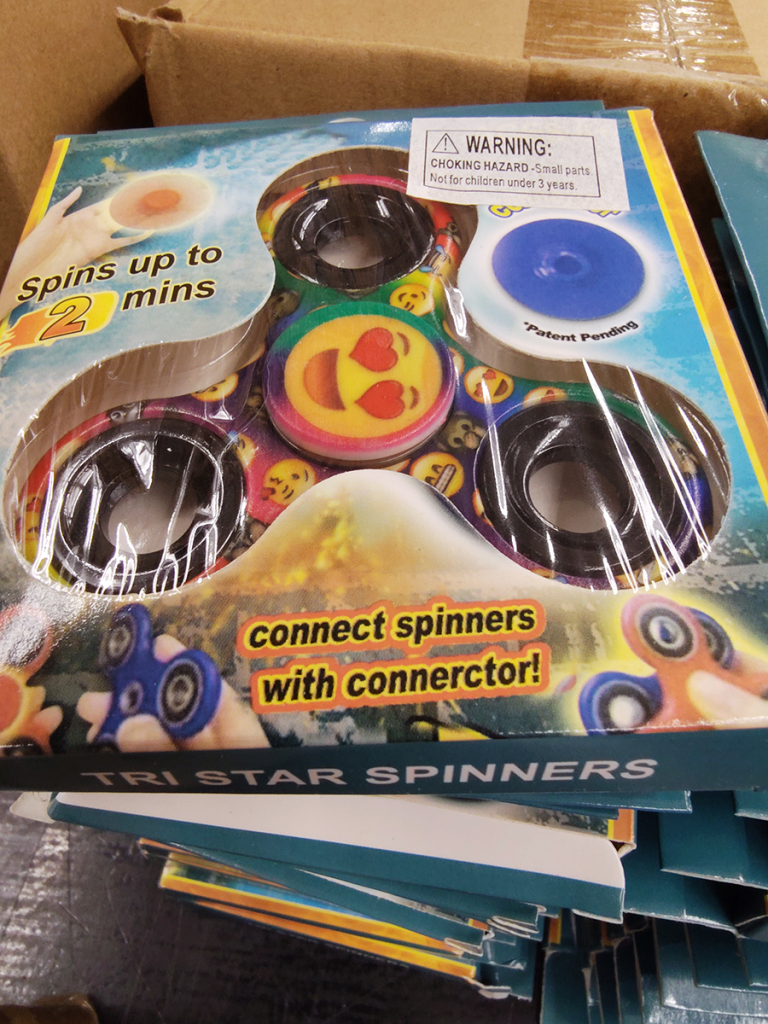

For one lab, run once each academic year, we need about a half teaspoon’s worth of tiny polystyrene pellets, the kind that get pressed together to make the cheapest, crappiest, least environmentally friendly coffee cups around. Altogether, in a busy lab year, that’s still maybe a third of a cup. And we can recover some of them, because we filter everything before pouring the liquid down the drain.

And we’ve got enough of them sitting in storage to last a couple of lifetimes at this rate. Or to fill up a bean bag chair.

But do open with caution. Those little pellets want desperately to stick to everything, to get everywhere.

Now we’re on to slightly more recent history, featuring an Aladdin lunch box thermos from 1976. The whereabouts of the lunch box – we’re assuming there was one, that’s how we recall our childhood – remain unknown.

It’s a full-on Avengers gathering, long before the juggernaut film universe took over the screens. The Amazing Spider-Man! Captain America!

The Incredible Hulk! Scarlet Witch! (Right? We’re not 100% caught up on pop culture down here in the basement.)

Thor, God of Thunder! Iron Man!

At last, Vision!

Okay, we had to look him up. We really are behind on the whole cinematic universe thing.

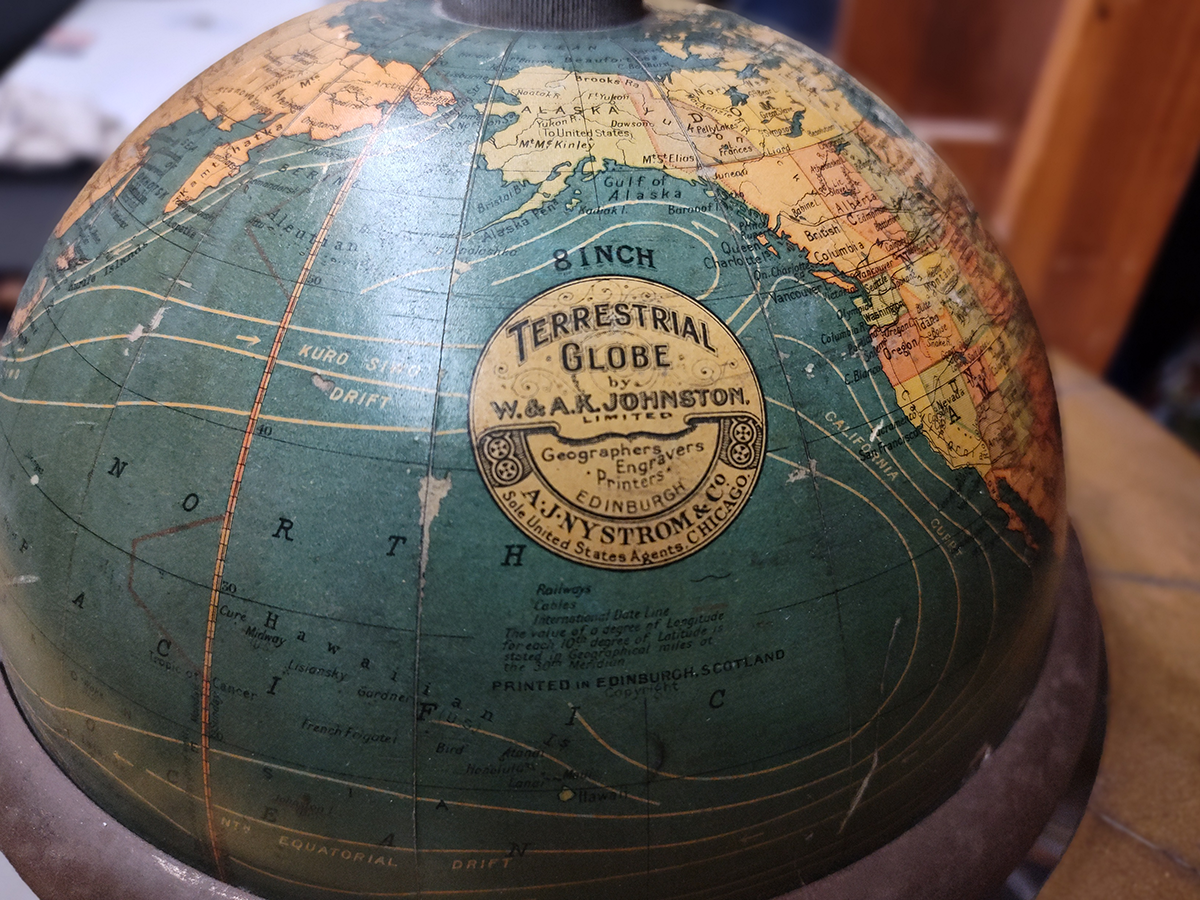

This odd-looking 8-inch globe occasionally comes out to illustrate the wobbly rotation of Earth’s precession, though it’s a pain to use and too small to see at a distance. Anymore, a gyroscope illustrates the concept more easily, so this old globe lives back in storage.

And when we say old, we mean it.

Okay, we jest about the “terrestrial globe” part. We have one moon globe around here, plenty of celestial sphere globes, including a big, fancy one also by W. & A.K. Johnston at the Observatory. If you want one of your own, an antiques dealer in Portland, OR is offering one just like ours for $6,500.

It does note copyright, but with no date. So how old could this be?

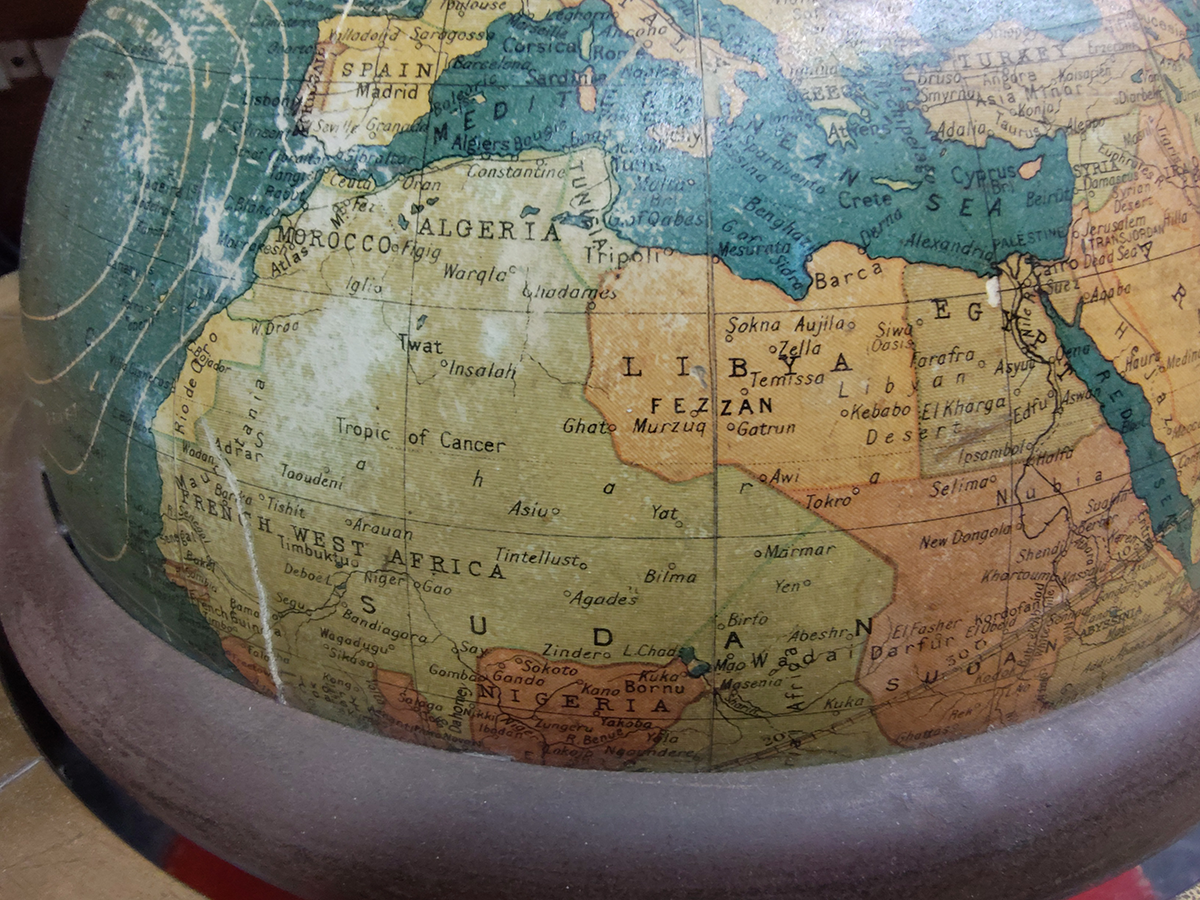

French West Africa existed from 1895 to 1958. Let’s begin with that range and see how much we can trim it down.

1895 | 1958

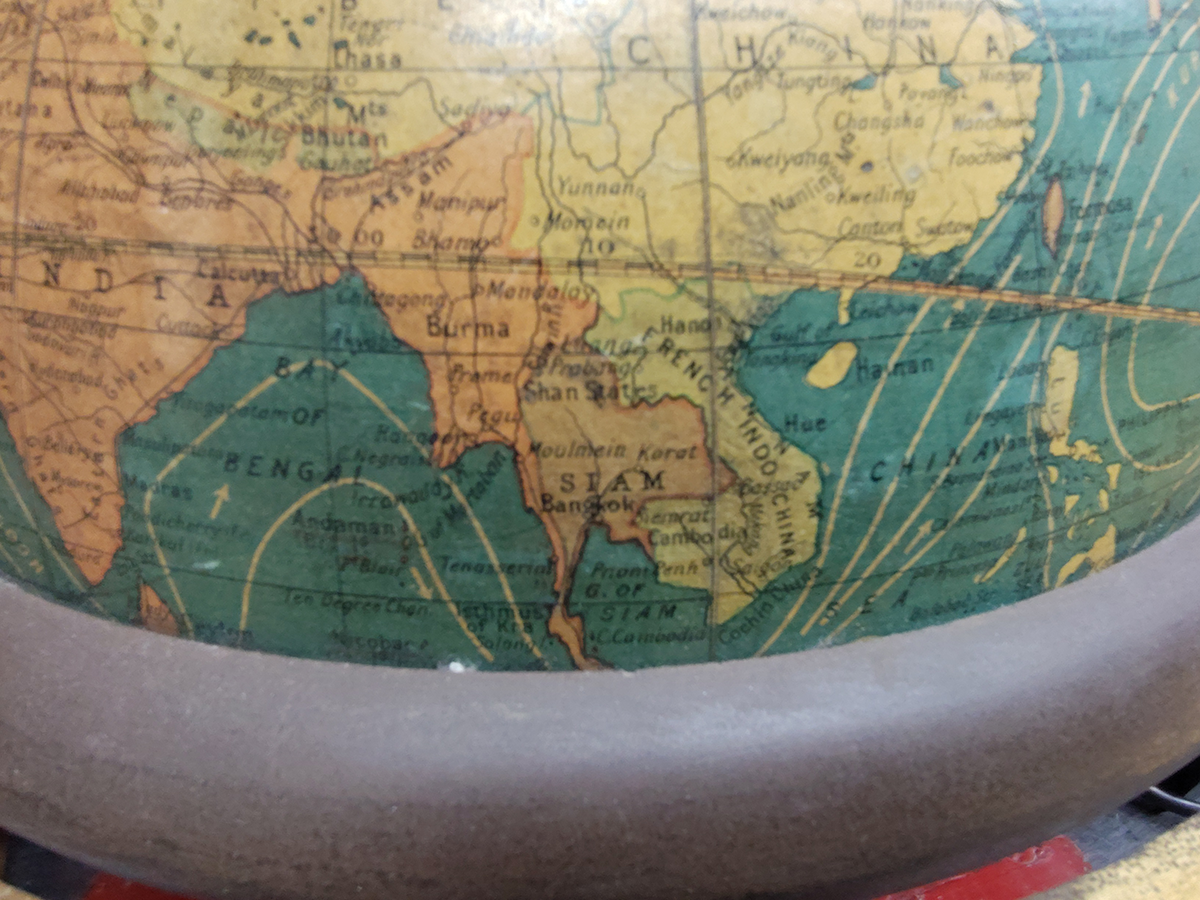

French Indochina existed from 1887 to 1954, so now we’re at:

1895 | 1954

We’re guessing that the big pinkish smear of India is the British Raj, 1858 to 1947.

1895 | 1947

Siam existed well earlier than that – argue for whatever – but changed to Thailand in 1939, so that gets us to:

1895 | 1939

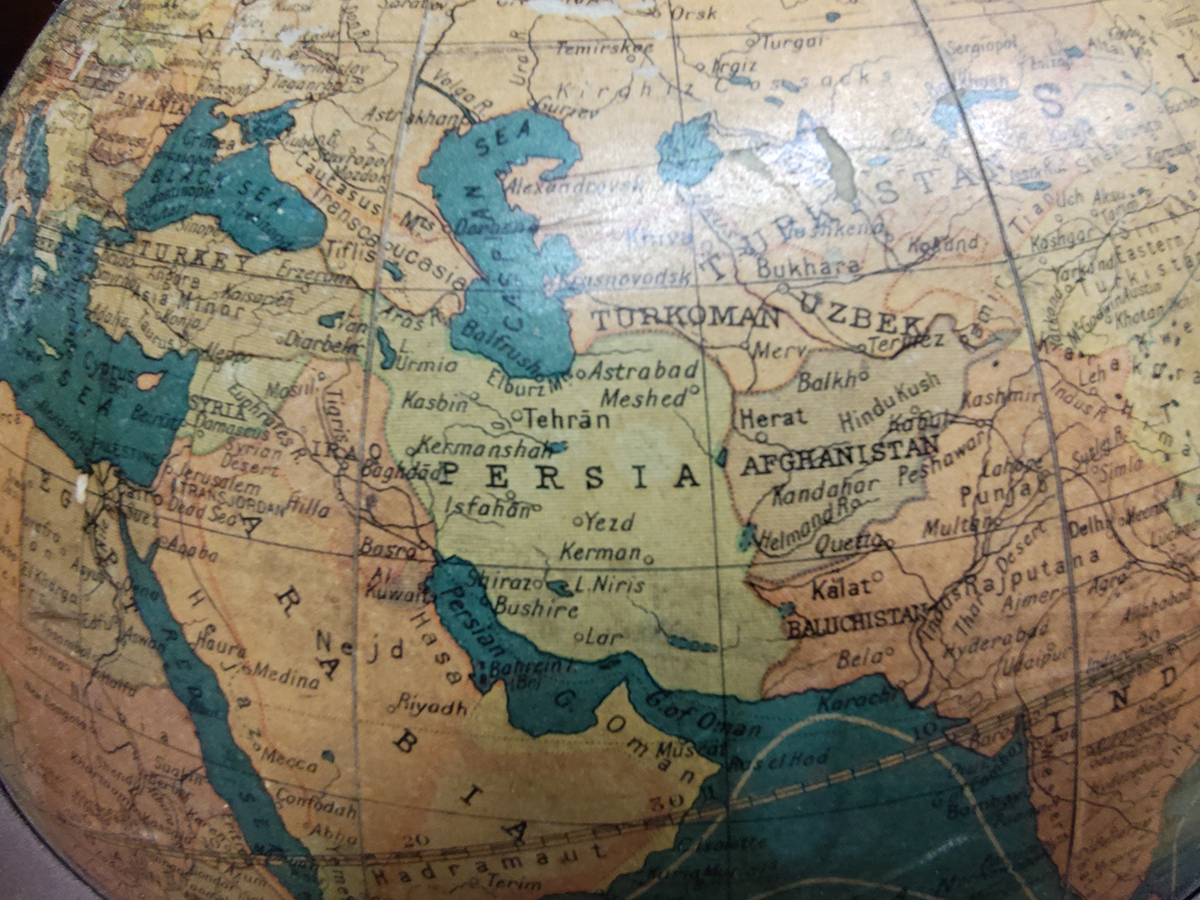

Persia brings some uncertainty, at least when used by a Scottish cartographer in the window we’re assuming, but let’s put the name change from Persia to Iran in about 1935. It’s a guess, but so is the rest of this.

1895 | 1935

Arabia is also a little vague, so we’re going to assign a range of 1902 (the return of Abdul-Aziz Al Saud and the capture of Riyadh from the Ottoman Empire) until 1930, the founding of the state of Saudi Arabia. We’re more confident about the latter date, but that’s the one that matters more.

1902 | 1930

Because we can also see Transjordan, the British-drawn territory which existed from 1921 until 1946. That further narrows our window to:

1921 | 1930

At last, we have one very big clue: the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. Sure, we remember the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 and the dissolution of the U.S.S.R. in 1991, but we know the globe’s older than that. We also know, from high school history class, that the U.S.S.R. came about following the Russian Revolution, which trims our earliest date to 1922.

1922 | 1930

So, an eight-year window, making this little globe about a century old. Probably. A lot can happen in a hundred years.

Physics doesn’t rely on field work as much as some other disciplines – biology, geology – but sometimes it’s necessary and the fresh air does us good. So do the occasional wild treats found along the trail.

Just be sure to share them with the local bears and birds!

Sure, the other side says soft white, but let’s be honest: blanco suave sounds way, way better.

In great big boxes full of boxes, the toys begin to arrive. We stash them in corners, in front of other shelves, any place mostly out of the way before separating, sorting, packing, and distributing.

Three hundred yo-yos, Imperials and Butterflies, in an assortment of colors. Every box is full of surprises!