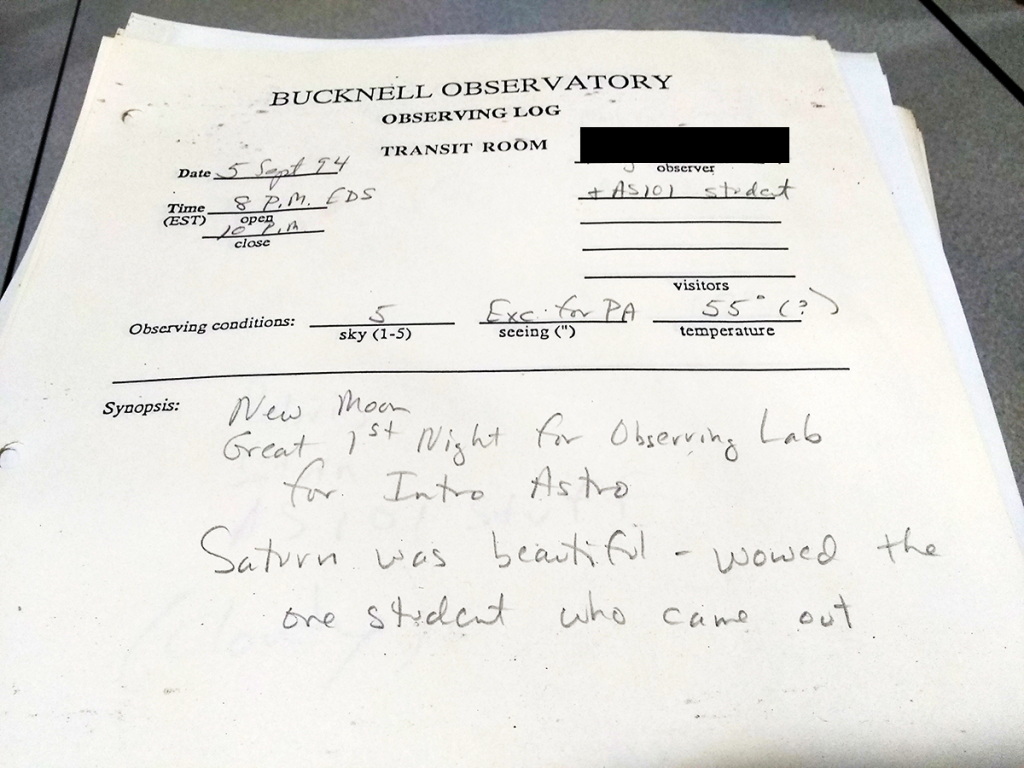

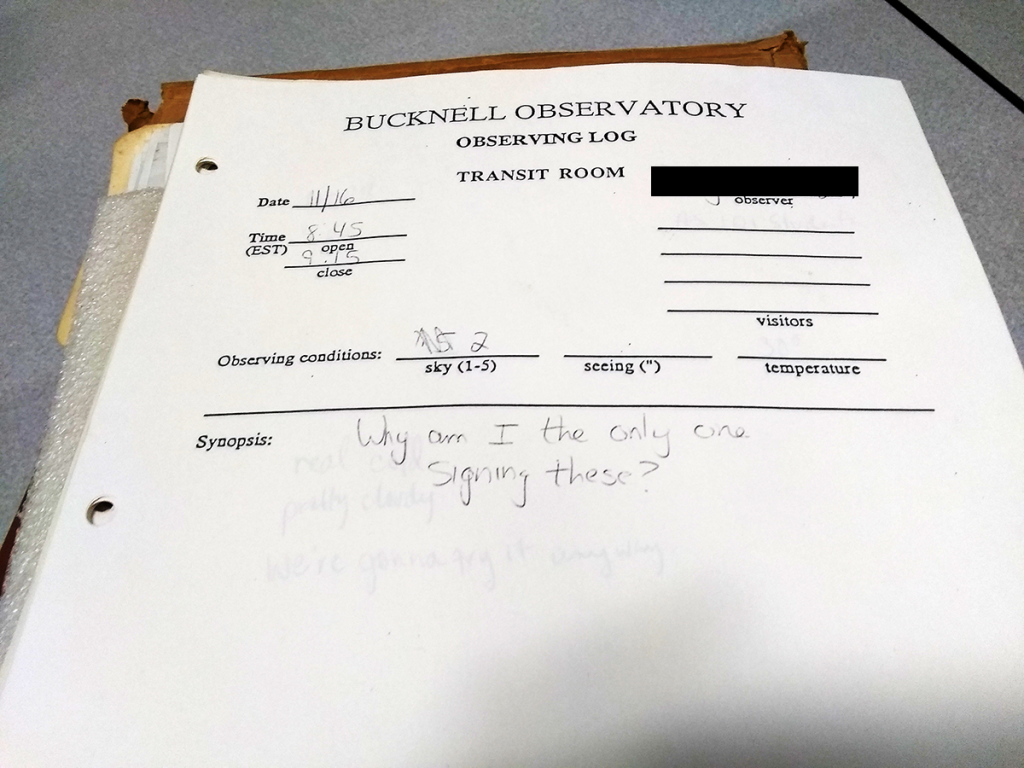

Your average TA for an Astronomy night lab is excited about their job. They not only took an Astronomy course, but liked it enough to come back. At night. Irregularly, as the weather permits, sometimes in the cold of a Pennsylvania winter. They’re enthusiastic about their job. We’re enthusiastic about them.

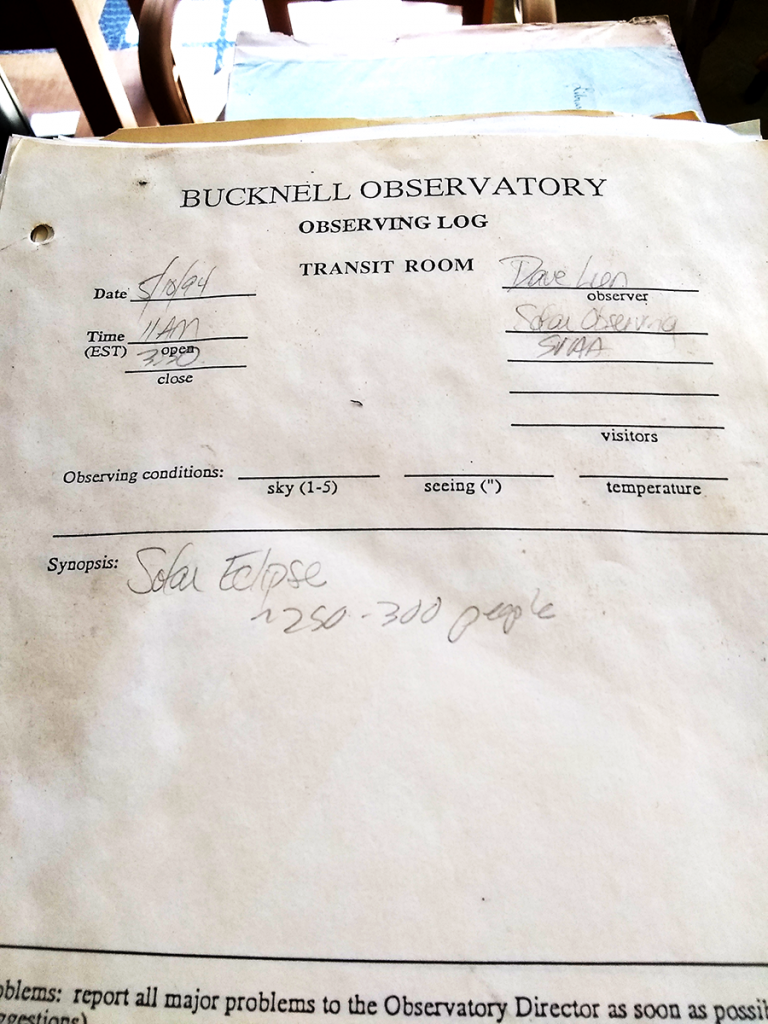

So when you find notes from almost three decades ago with student gripes? Totally understand. We wish every student could bring the same excitement to a night with telescopes and stars.

And, for the record: Saturn absolutely is beautiful through a telescope on a night with no moon. Just phenomenal.