There’s a funny thing about important scientific discoveries. The effort and time and careful data collection and building atop previous understandings and innovations and everything else is daunting, difficult, and a massive undertaking. Critical details and a fine understanding may take months, years, or entire careers. A general grasp, though?

Sometimes, you can explain the gist of things with stuff that’s just lying around.

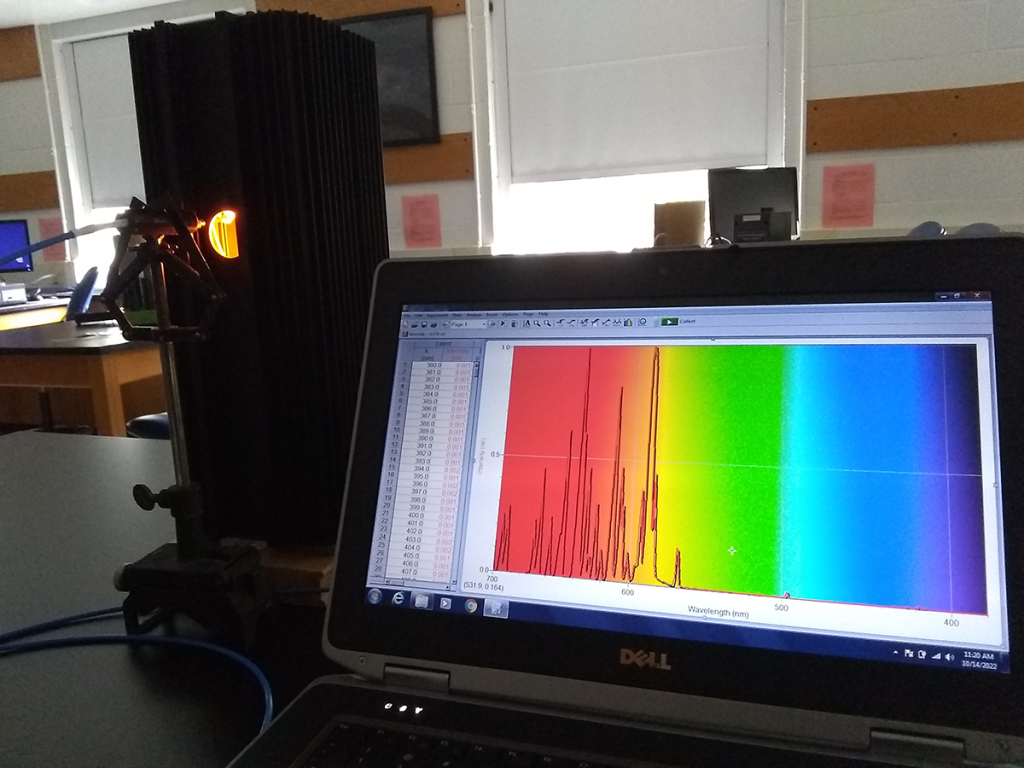

Hubble’s Law, also known as the Hubble-Lemaître Law, describes the expansion of the universe. Galaxies are moving away from ours, and the further away they are, the faster they’re moving. Getting there relied on the Friedmann equations – themselves built upon Einstein’s general relativity – plus Slipher’s redshift measurements of distant galaxies, plus the debates between Shapley and Curtis, plus an understanding of the relationship between luminosity and period in the pulsations of Cepheid variable stars. (They’re like the drinking bird toys of stars.) Plus more, and more, but you get it. A lot goes into explaining the expansion of the universe when all you’ve got is a telescope and spectrometer.

Hubble ran into a real hiccup here. If everything in the universe is moving away from us, and we can correlate the distance and speed in any direction, doesn’t that imply that we’re at the center of the universe? Turns out, no. We’re not.

And you can illustrate the principle with a Slinky, a ruler, and some paper clips.

We get a lot of mileage out of the Slinky.