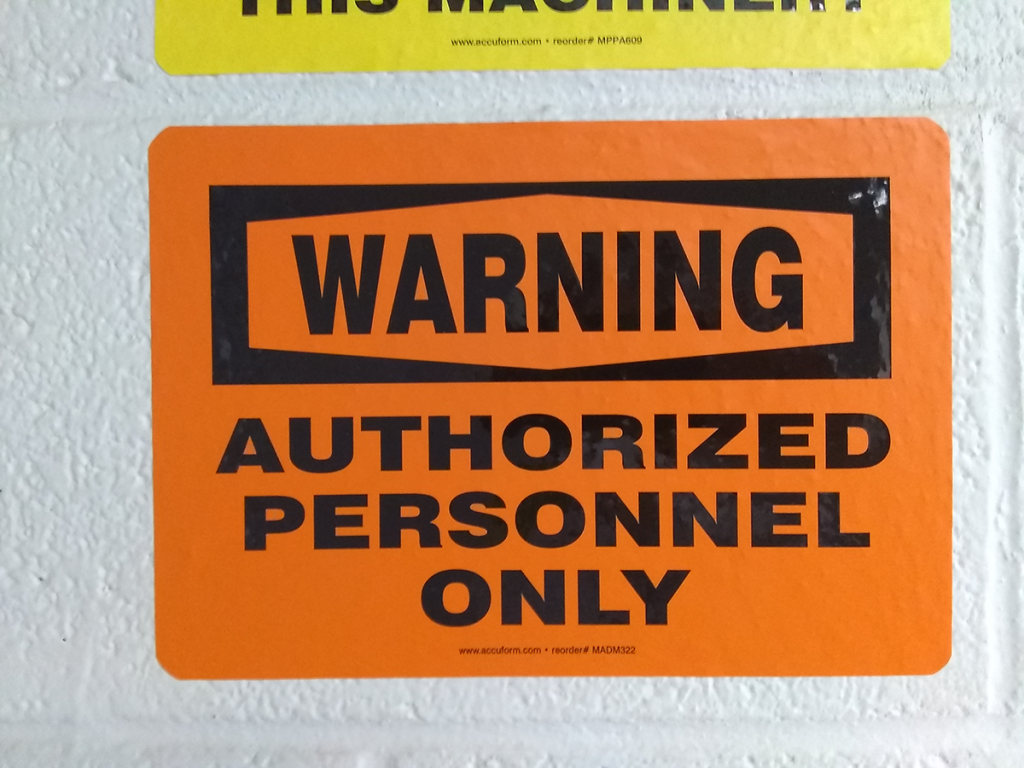

Signs! They’re all around, some not-so-subtle hints to remind you that you’re in a working machine shop full of dangerous things. There’s an informal ranking of which tools qualify as the most dangerous, but improper use can make anything a hazard. So it’s safety goggles required, watch your fingers, and don’t touch anything you haven’t been trained to operate safely.

Can we assume you understand that open-toed shoes are a no-go?

Hazard signs have a hierarchy, beginning with CAUTION, often in yellow. Caution tells you that you’re in a potentially hazardous place, and failure to take appropriate precautions could result in injury. Safety goggles around the machines, please. Don’t press any switches unless you know what they do.

Next step up: WARNING. The situation here is moderately hazardous. Failure to take appropriate precautions could result in death or serious injury. Maybe not likely, but please don’t lose a finger to the bandsaw. Keep those knuckles well away from the business end of the belt grinder.

And at the top, DANGER. Oh, danger. You get the quality of imagery that belongs on packs of cigarettes. Danger tells you that certain situations will result in death or serious injury. Not might, but will. Do not mess around with the table saw. Do not allow loose clothing or hair anywhere near the lathe. We like gallows humor for some very good reasons.

Nothing quite like the worst-case outcome for Charlie Chaplin in Modern Times laid out for you in stark silhouette.