Oh, right. Some days, you might forget that we share one of our storage spaces with the Theater & Dance department.

Discoveries in the Physics & Astronomy shop | Science, curiosities, and surprises

Oh, right. Some days, you might forget that we share one of our storage spaces with the Theater & Dance department.

Sometimes you stumble across a delightful artifact. One with an unknown, perhaps unknowable history. Clearly, at one point, it was necessary to hold an object in a particular place, and none of the available clips, clamps, or clasps were up to the task.

A steel rod, an alligator clip, and some electrical tape to the rescue!

What’s fascinating about this isn’t the specifics of the object, but the way that these temporary, stopgap solutions can linger. After enough time and use, they become ordinary and unremarkable. Familiar.

Until, some indefinite period of years later, a fresh set of eyes spots them in an old drawer. Look at what’s in here!

It really wasn’t that long ago that computers came equipped with optical disc drives, and they were effective means of data storage, and the density you could store on a DVD instead of a CD was pretty exciting. Now? They’re not only borderline-useless, but the features that we used to reference as a cultural touchstone are no longer obvious to our students.

It’s not that they don’t know what these are. It’s that they haven’t handled a million of them to know their dimensions, to understand the diffraction rainbow they make. The physicists around here remember using the inescapable AOL discs as cheap, readily available diffraction gratings back in grad school. The astronomers use their proportions to illustrate the shape of the Milky Way Galaxy. Students now need to physically hold one of these to get the idea, because they don’t have a mental image ready to go.

Our Galaxy, if you were wondering, is roughly proportioned as a CD, only instead of being a millimeter and a half thick, is more like 1,000 light years. Very roughly, anyway.

Strange things come through the shop doors some days. This one perfumed the shop for a time, a bamboo cutting board which had been resting on a hot electric coil. Everything smelled like burnt corn husk.

Everything. It was a pervasive scent, intriguing at first and overwhelming after a time.

Scraped, chiseled, sanded, and… well, not exactly like brand new, but in usable shape once again!

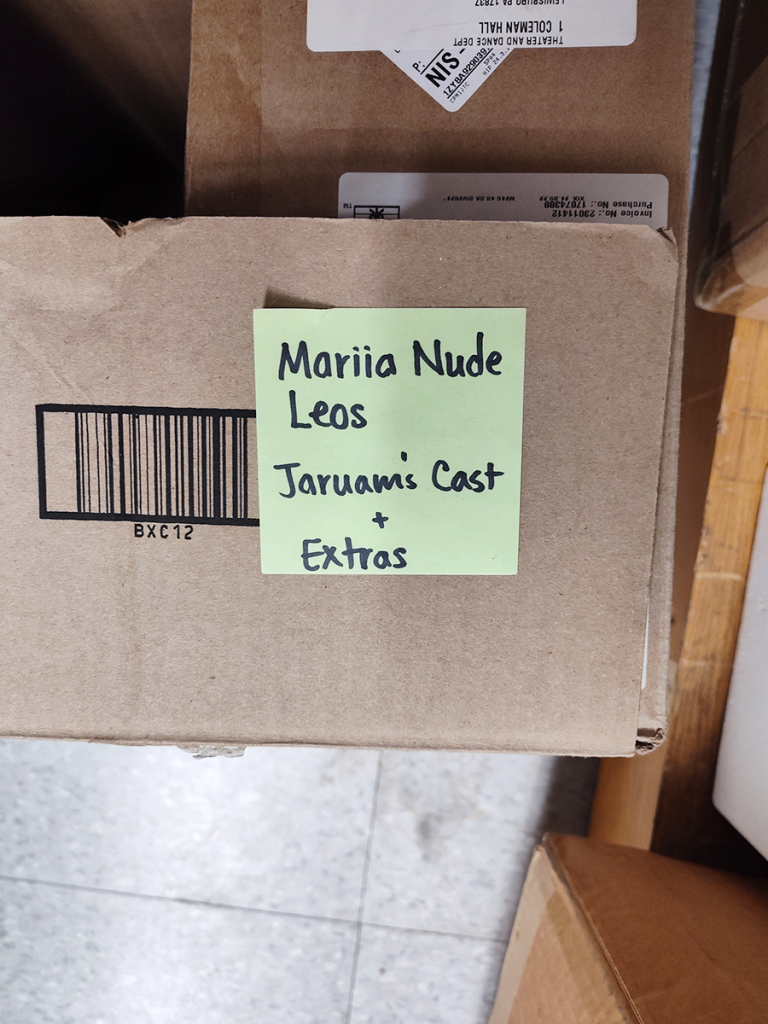

Astronomy, here and elsewhere often under the Physics umbrella, was once part of the Mathematics department at Bucknell. Occasionally, we’ll stumble across some old files in the Observatory that have been yellowing gracefully for decades. Like this two-part final exam from Math 101. Algebra!

Of note for context: this old exam – November 15th, 1948 – waited patiently in a filing cabinet at the current Observatory, built in 1963. In all likelihood, it sat in a folder in the old Observatory for thirteen years, transferred to Tustin Gym for a time, and then quietly continued to be forgotten in a new building until some tech decided to clean the place up a bit.

Who doesn’t love finding curiosities in purple ditto ink?

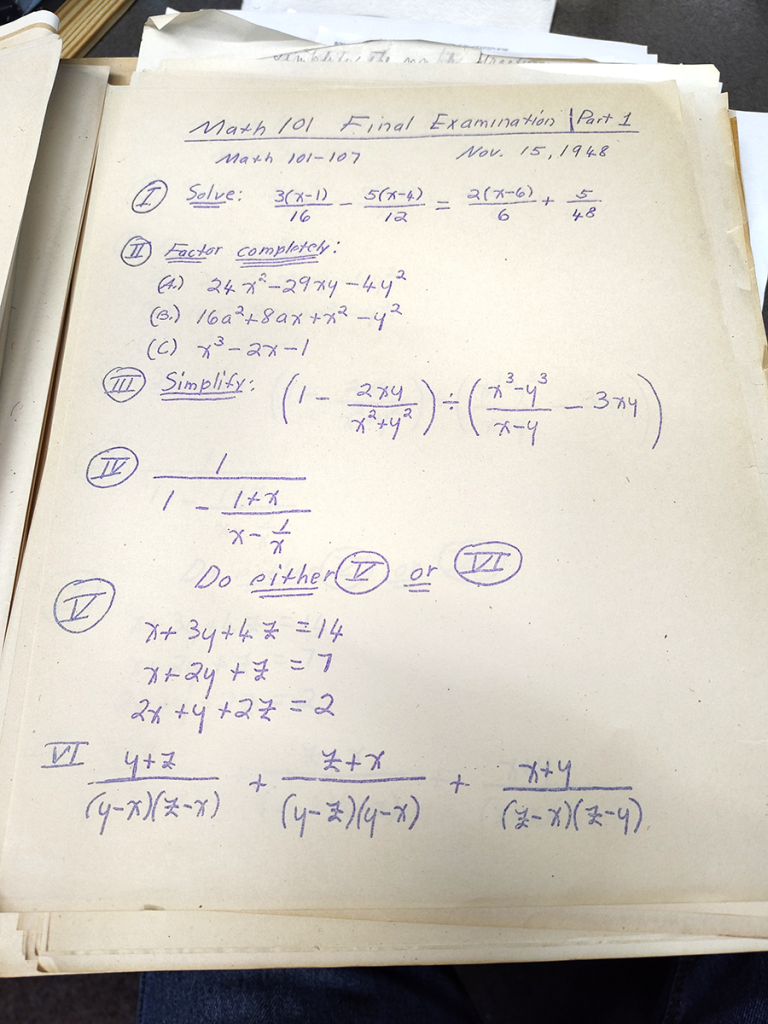

Lead bricks are useful things. This one – still bearing the stamp of Nuclear Associates, of Carle Place, NY – has had its fair share of scuffs and dents. (Lead’s soft stuff, you know.) These days it functions as a handy doorstop and a hands-on tool for explaining the density of matter.

Denser than water, than aluminum, than a nickel-iron meteorite. (All easy samples to acquire for demonstration.) Less dense than osmium; about half as much. (Not on hand, unfortunately.) Definitely less dense than the core of our Sun, by an order of magnitude-plus.

Also no handy samples of stellar core plasma on hand.

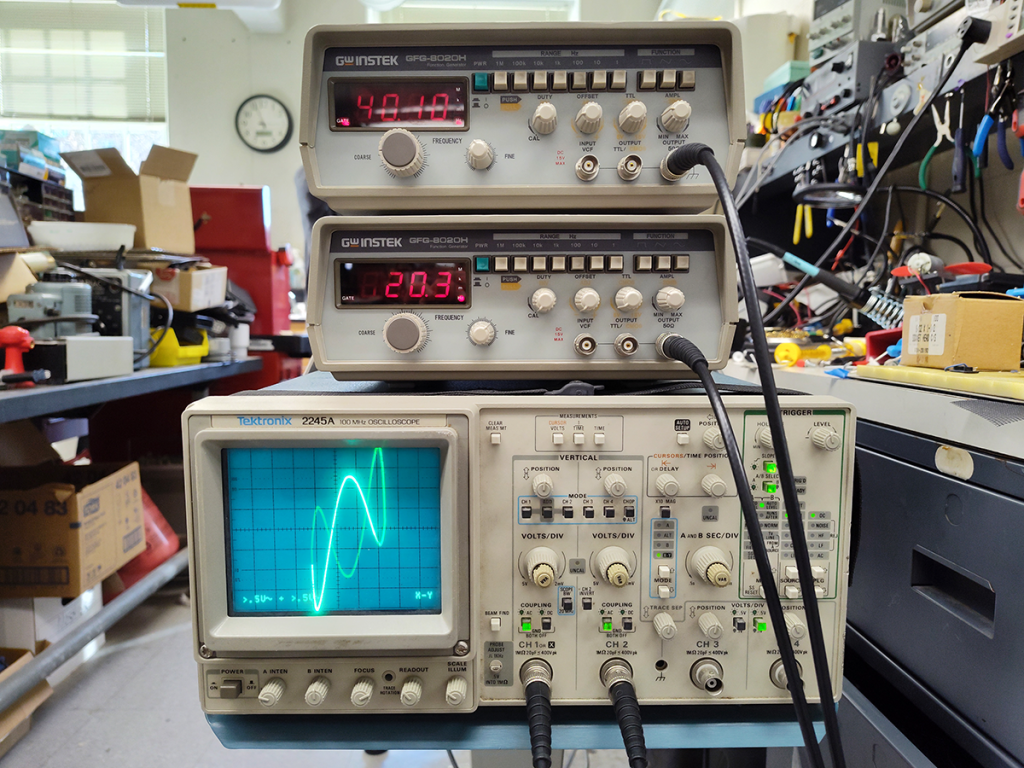

Take two function generators, an old CRT oscilloscope, a couple of power and BNC cables, and look! Whirling, dancing lissajous figures!

Chunky knobs! Clicky buttons! Drifty outputs! Squiggly curves!

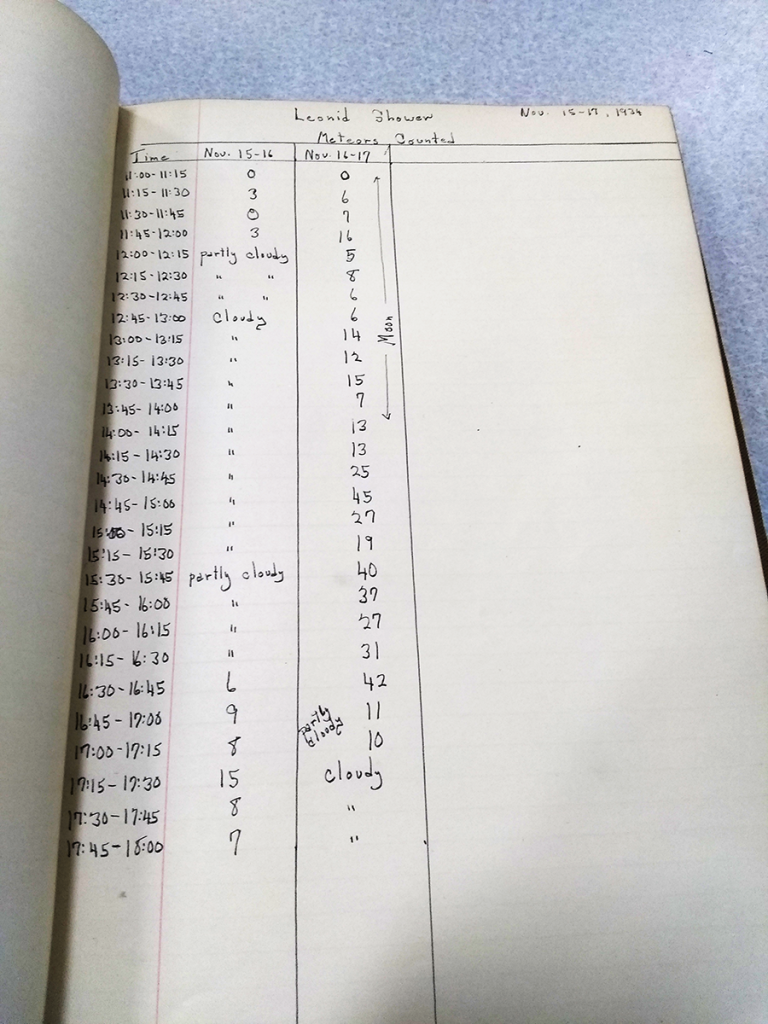

Ninety years ago, during the Leonids meteor shower, someone was counting a lot of burning bits of debris from comet 55P/Tempel-Tuttle. With one fifteen-minute window boasting forty-five meteors (!), that’s a powerfully active shower. Not quite a storm, but those happen with the Leonids sometimes.

According to NASA, the Leonids peak about every 33 years, with 1966 being a spectacular meteor storm. In one fifteen-minute window, thousands of meteors fell like glowing rain. How amazing is that?

Also: check out the times indicated. We’re assuming the counting started at 11:00pm and ran until early morning, with a 24-hour clock opposite how we’d expect it. (Maybe sleep deprivation?) Either that or it was a truly spectacular meteor shower!

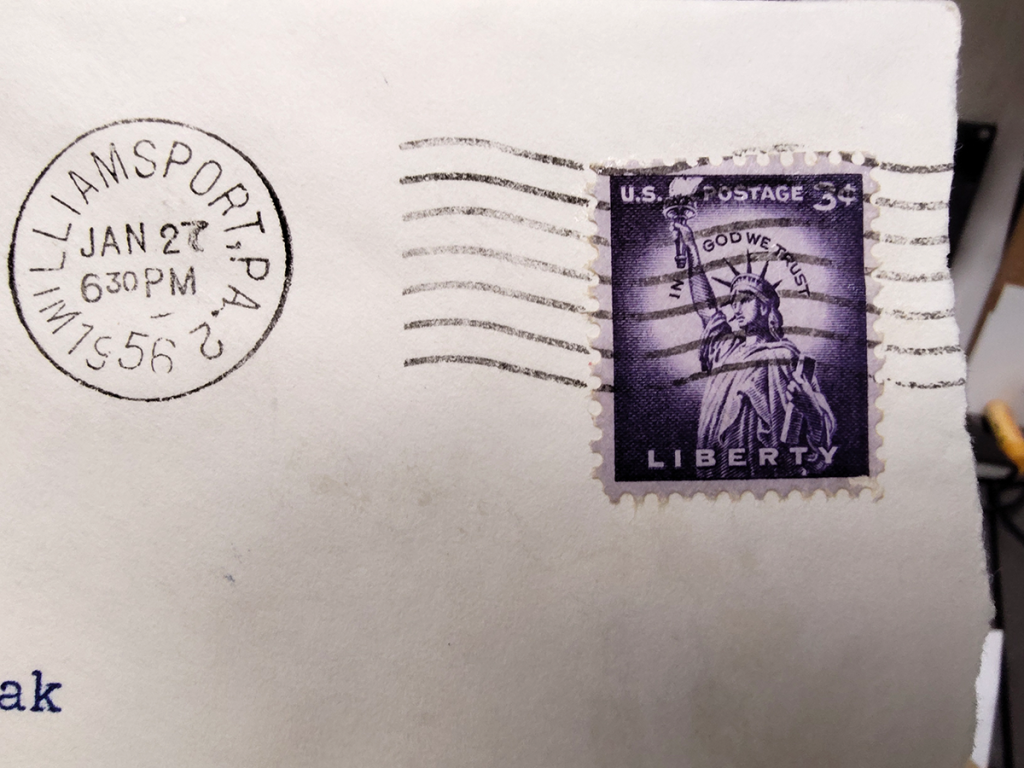

First class postage as of January 27th, 1956 cost three cents.

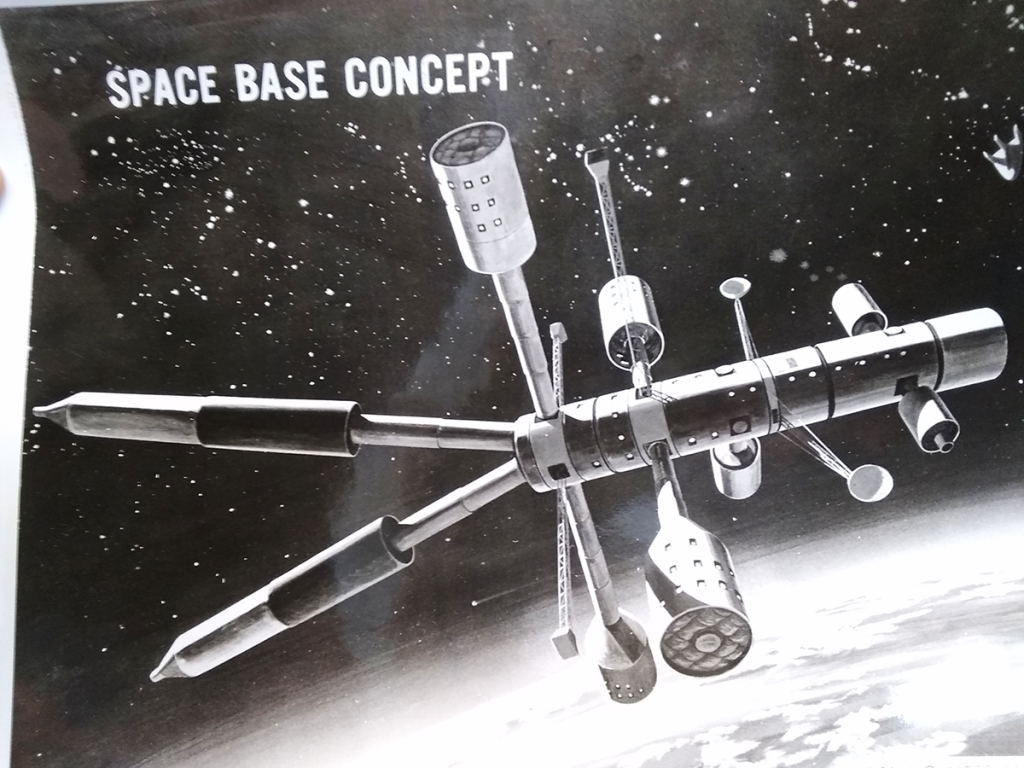

Sometimes you stumble across an old gem in the lost files and piles of forgotten stuff. Space base!