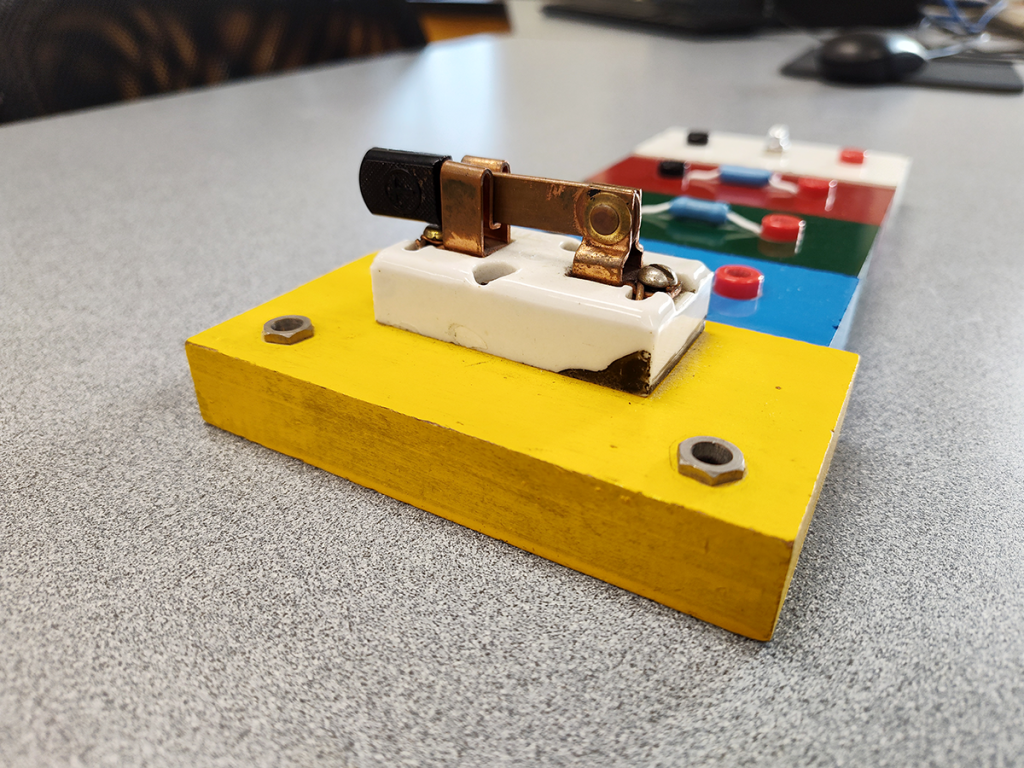

When learning about the laws of Ohm and Kirchhoff, it helps to have some hands-on experimentation, wiring together batteries and resistors and tiny little incandescent bulbs. Try it, see what happens, measure your voltage and current. Simple enough, yet more satisfying and memorable than just drawing squiggles on paper.

Plus, you get to open and close the switch like a tiny Frederick Frankenstein! Just try to resist the urge to shout out “My Creation Lives!” too loudly.