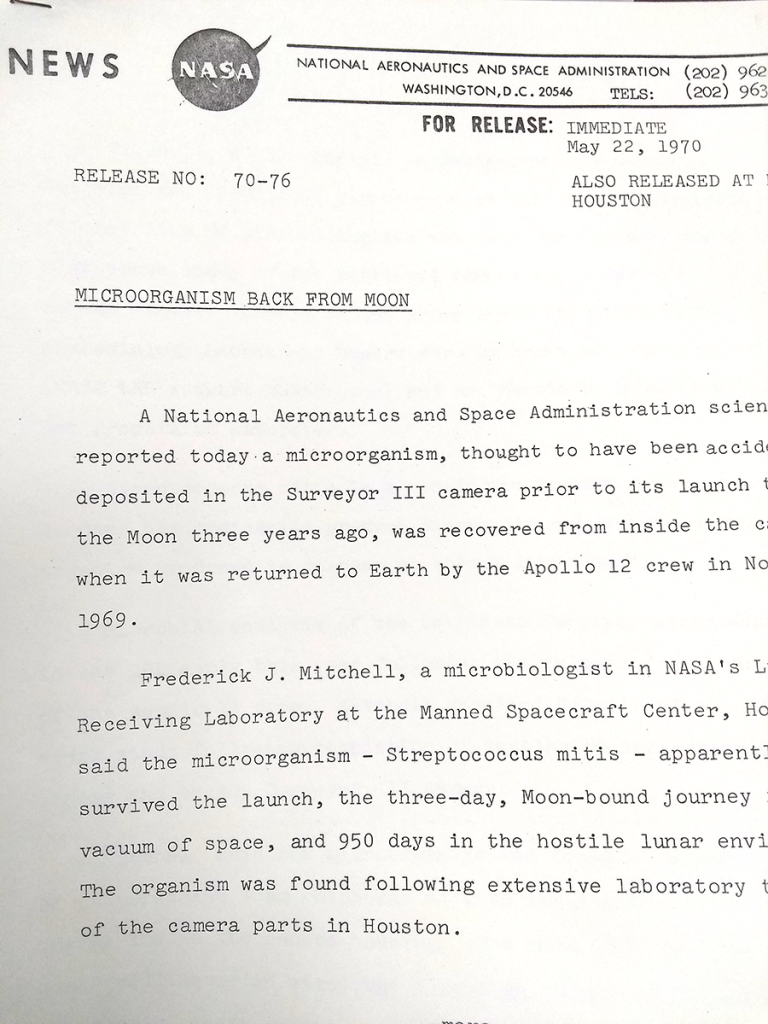

On further reflection, it was probably contamination after the return to Earth, but we still like the idea of mouth bacteria being just fine with two and half years on the Moon.

Brush your teeth, kids.

Discoveries in the Physics & Astronomy shop | Science, curiosities, and surprises

On further reflection, it was probably contamination after the return to Earth, but we still like the idea of mouth bacteria being just fine with two and half years on the Moon.

Brush your teeth, kids.

From the days before planetarium software was readily available, we have an intense glut of celestial globes, which show the positions of the stars and constellations on the night sky. Also the day sky, of course, but unless you’re watching a total solar eclipse they get lost in the bright blue light scattered by our atmosphere. They get little use except as office decorations.

We have two Earth globes – one is a giant, inflatable beach ball – which still get regular use in Astronomy classes. Unsurprisingly, visualizing the movement of an Earthbound observer on a tilted, rotating, orbiting planet around the sun isn’t always intuitive. Having a mini-Earth to look at helps immensely.

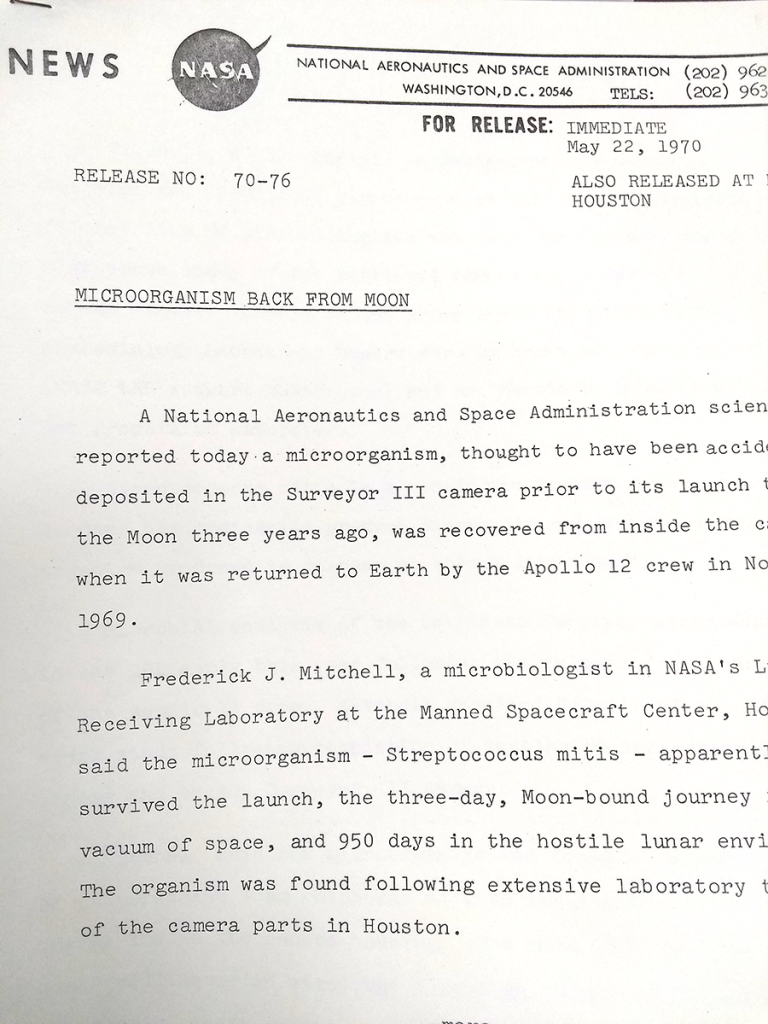

We also have a very nice lunar globe, which really should see more use. It’s highly detailed, including on the side of the moon that only a handful of humans have ever seen. (More craters, fewer mare.) If you dig maps, it’s a very cool map.

And when did this charming item come into being? 1969, of course.

It is possible to snap a photo of the moon through the antique Clark refractor telescope. It’s just not very easy.

It’s no surprise that there are books everywhere. This is a university, after all. Books are one of the biggest threads connecting every department and avenue of study.

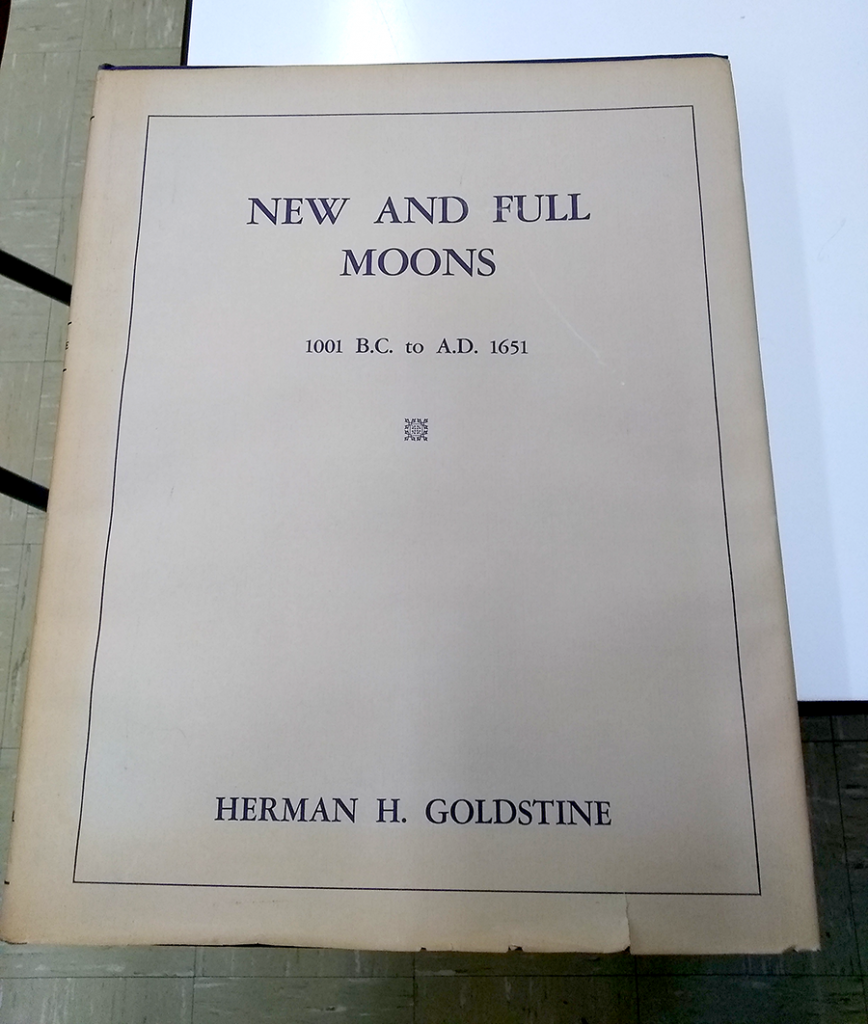

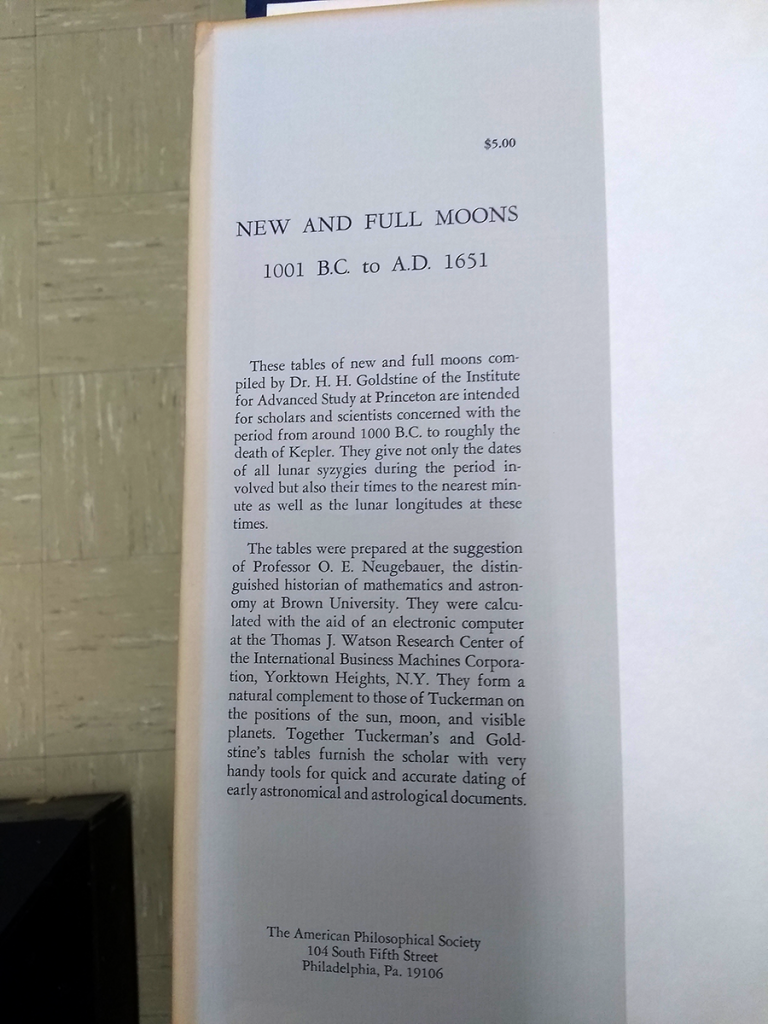

Sometimes it’s fun to flip open some of the old tomes gathering dust on mostly-forgotten shelves. This was, presumably, a useful reference when acquired in 1973 or so. Flipping open the front cover, it’s not hard to imagine that someone got at least $5 worth of use out of this.

That said, this is not the most compelling cover-to-cover read, unless you’re really into data tables for the sake of data tables. Front to back, it’s tables of lunar positions and times over a span of 2,652 years. From what seems like an arbitrary start – 1,001 is a pretty fine number – to around the death of Johannes Kepler (November 1630) makes for a lot of potential eclipses and other lunar phenomena that would get the attention of ancient writers.

Folks around here are already talking seriously about the solar eclipse in April of 2024. Syzygies are a big deal.

Syzygy. Y-Y-Y. Great word.