It’s for the Observatory, obviously.

Discoveries in the Physics & Astronomy shop | Science, curiosities, and surprises

It’s for the Observatory, obviously.

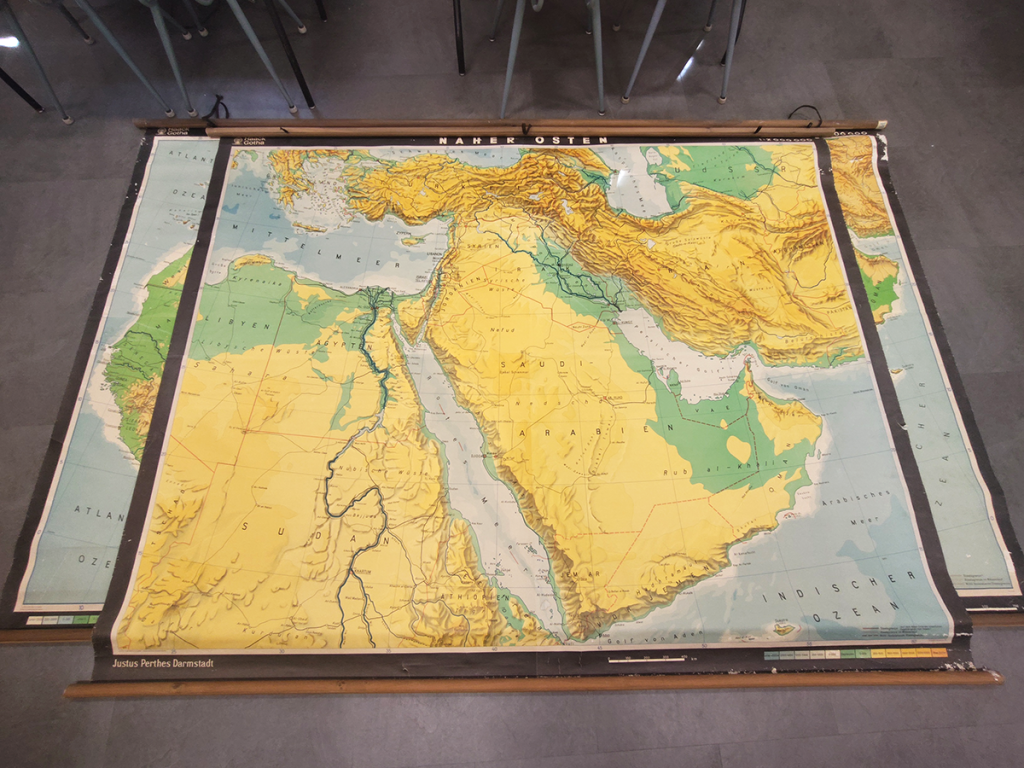

Of course there’s a second enormous map, just as inexplicable. Same German cartographers, same 1990s era, same corner of the Observatory.

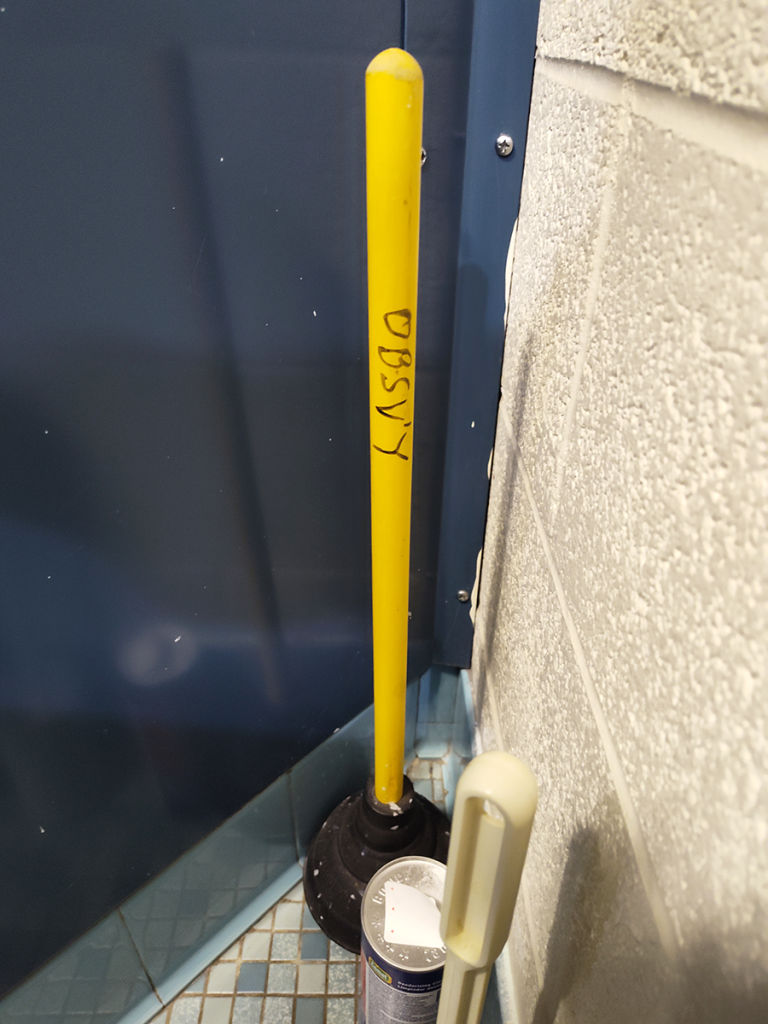

This one’s the Middle East, or in German, Naher Oster (Near East). We’re sure there’s an interesting story on why the nomenclature’s similar but distinct in different European languages.

We’re not sure why these were set aside here, but at least they’re neat?

We can make guesses – both educated and wild – as to why this enormous map of North Africa was tucked away in the corner of an Observatory classroom. This all-in-German map. From the 1990s.

It’s in good shape, and kinda cool in its own way. Just borderline inexplicable.

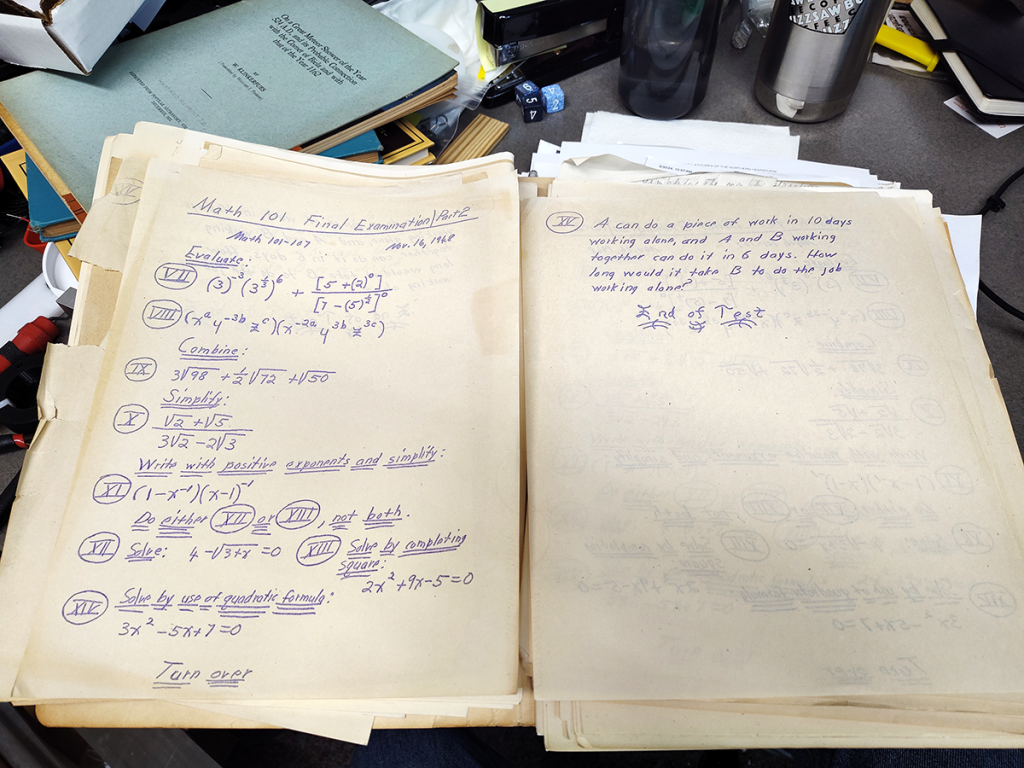

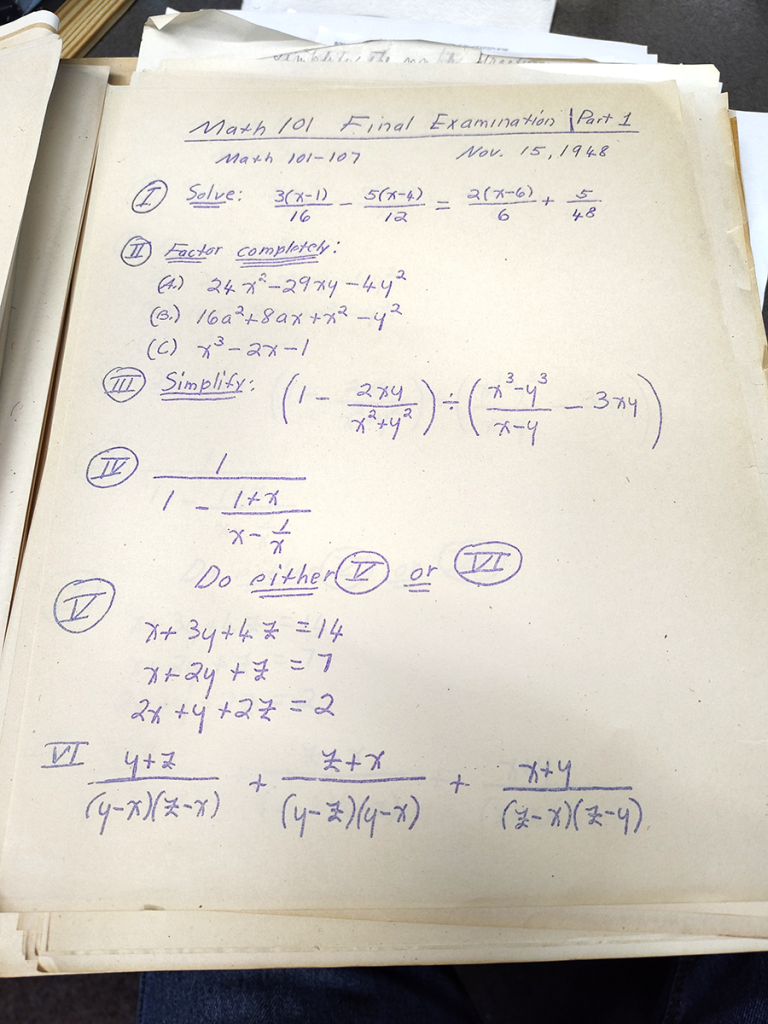

It’s part two of our Math 101 algebra final!

Someone really likes to underline for emphasis. They did not want the students to miss that the quadratic formula would be essential for solving 3x2 – 5x + 7 = 0.

Of course, nothing’s as charming as the wiggly, fancily-underlined “End of Test” text. Right?

Astronomy, here and elsewhere often under the Physics umbrella, was once part of the Mathematics department at Bucknell. Occasionally, we’ll stumble across some old files in the Observatory that have been yellowing gracefully for decades. Like this two-part final exam from Math 101. Algebra!

Of note for context: this old exam – November 15th, 1948 – waited patiently in a filing cabinet at the current Observatory, built in 1963. In all likelihood, it sat in a folder in the old Observatory for thirteen years, transferred to Tustin Gym for a time, and then quietly continued to be forgotten in a new building until some tech decided to clean the place up a bit.

Who doesn’t love finding curiosities in purple ditto ink?

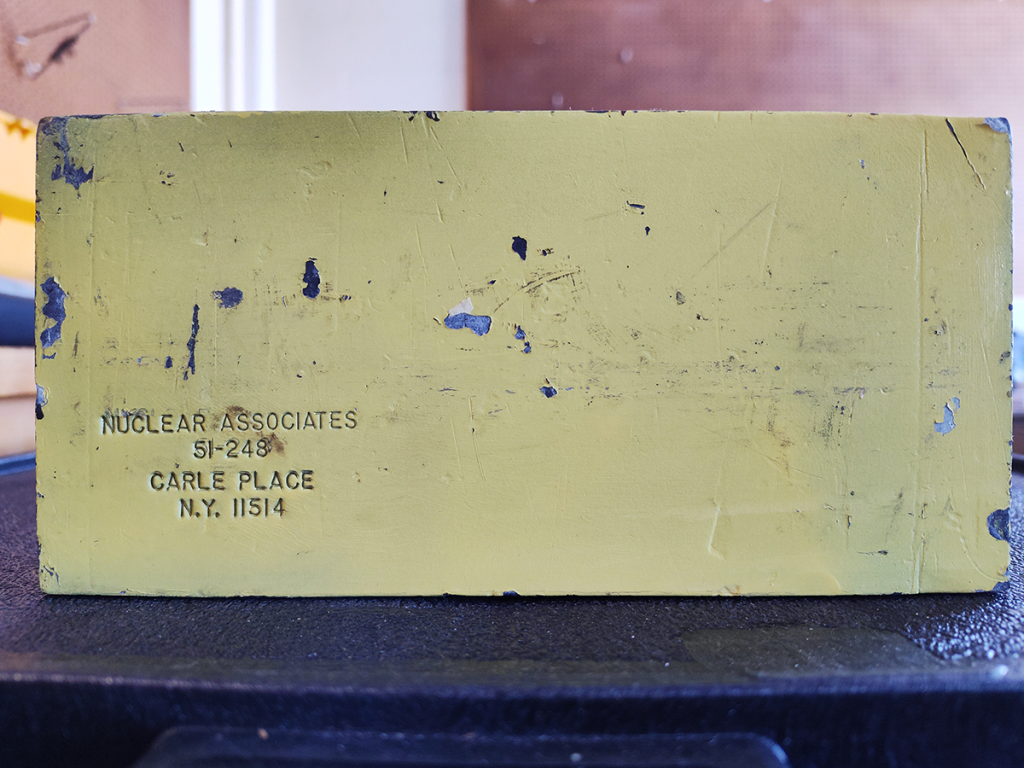

Lead bricks are useful things. This one – still bearing the stamp of Nuclear Associates, of Carle Place, NY – has had its fair share of scuffs and dents. (Lead’s soft stuff, you know.) These days it functions as a handy doorstop and a hands-on tool for explaining the density of matter.

Denser than water, than aluminum, than a nickel-iron meteorite. (All easy samples to acquire for demonstration.) Less dense than osmium; about half as much. (Not on hand, unfortunately.) Definitely less dense than the core of our Sun, by an order of magnitude-plus.

Also no handy samples of stellar core plasma on hand.

And we’re back from break. Snow!

We have several murals on display at the Observatory for those with time to look around. That includes ol’ Helios here, with a real Mona Lisa smile going on.

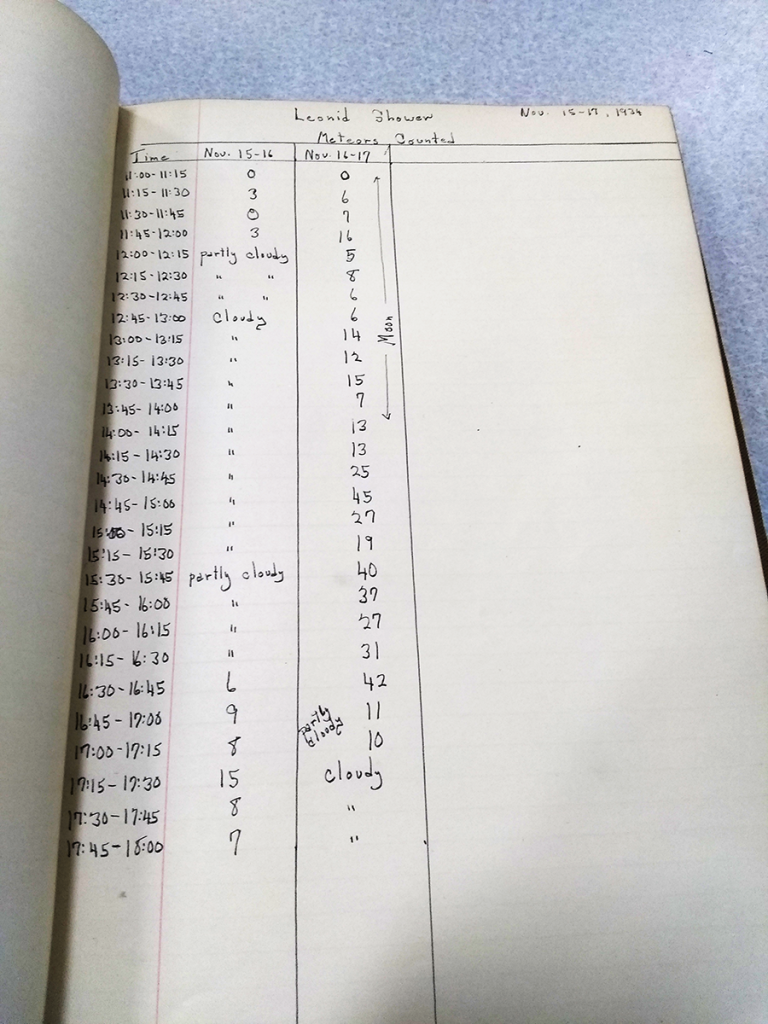

Ninety years ago, during the Leonids meteor shower, someone was counting a lot of burning bits of debris from comet 55P/Tempel-Tuttle. With one fifteen-minute window boasting forty-five meteors (!), that’s a powerfully active shower. Not quite a storm, but those happen with the Leonids sometimes.

According to NASA, the Leonids peak about every 33 years, with 1966 being a spectacular meteor storm. In one fifteen-minute window, thousands of meteors fell like glowing rain. How amazing is that?

Also: check out the times indicated. We’re assuming the counting started at 11:00pm and ran until early morning, with a 24-hour clock opposite how we’d expect it. (Maybe sleep deprivation?) Either that or it was a truly spectacular meteor shower!

Wow. Just, wow.