Currently, it’s the season for birds to nest in odd cracks and corners, necessitating regular cleanouts until they or we give up. At least the view’s a nice one on a good day.

Discoveries in the Physics & Astronomy shop | Science, curiosities, and surprises

Currently, it’s the season for birds to nest in odd cracks and corners, necessitating regular cleanouts until they or we give up. At least the view’s a nice one on a good day.

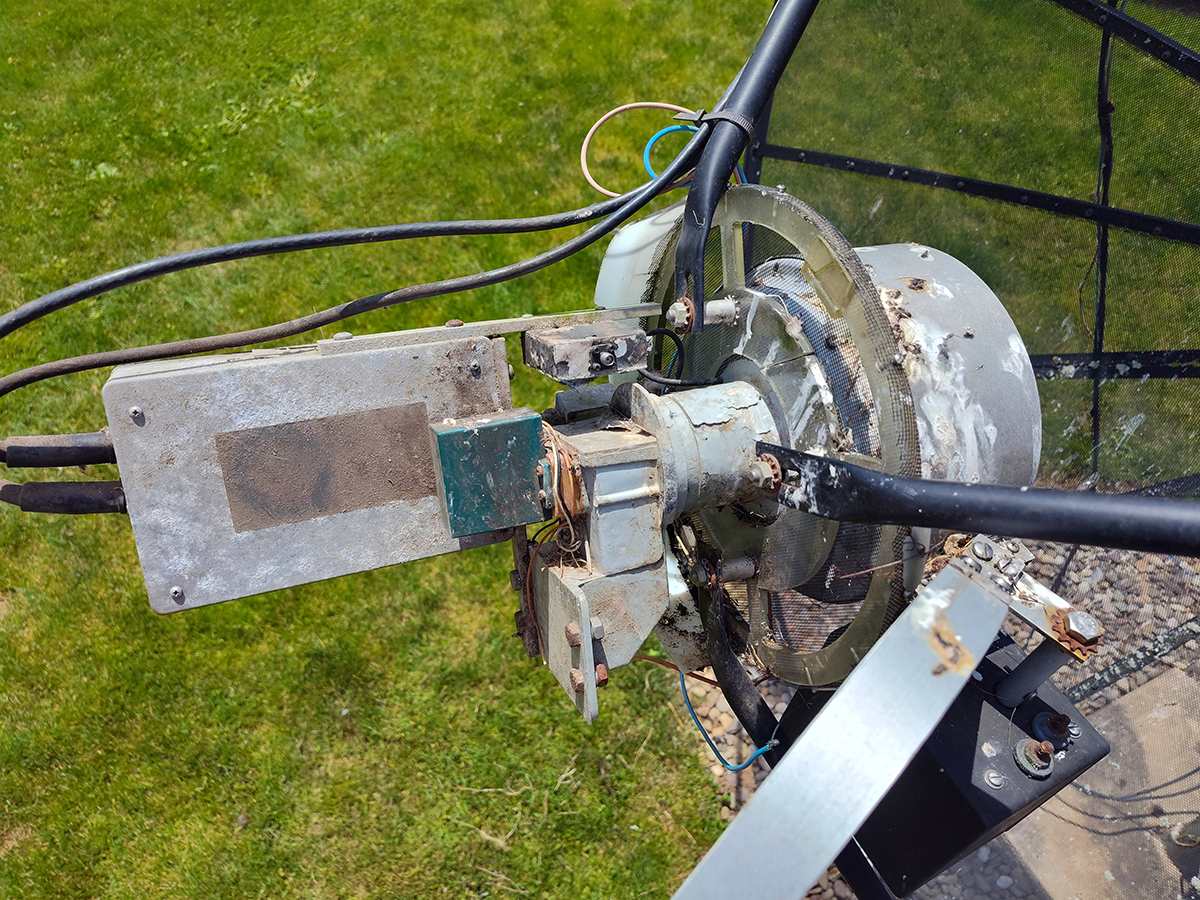

After enough years of outdoor UV exposure, temperature fluctuations, and who knows what all else, most plastics start to break down. The thin support ring – looks like polyethylene of some sort – has started to crumble, and the radio telescope’s nose cone is hanging loosely.

Inside, the receiver and amplifier appear to be in good enough shape. Note that many birds and many bugs have made a real mess of things.

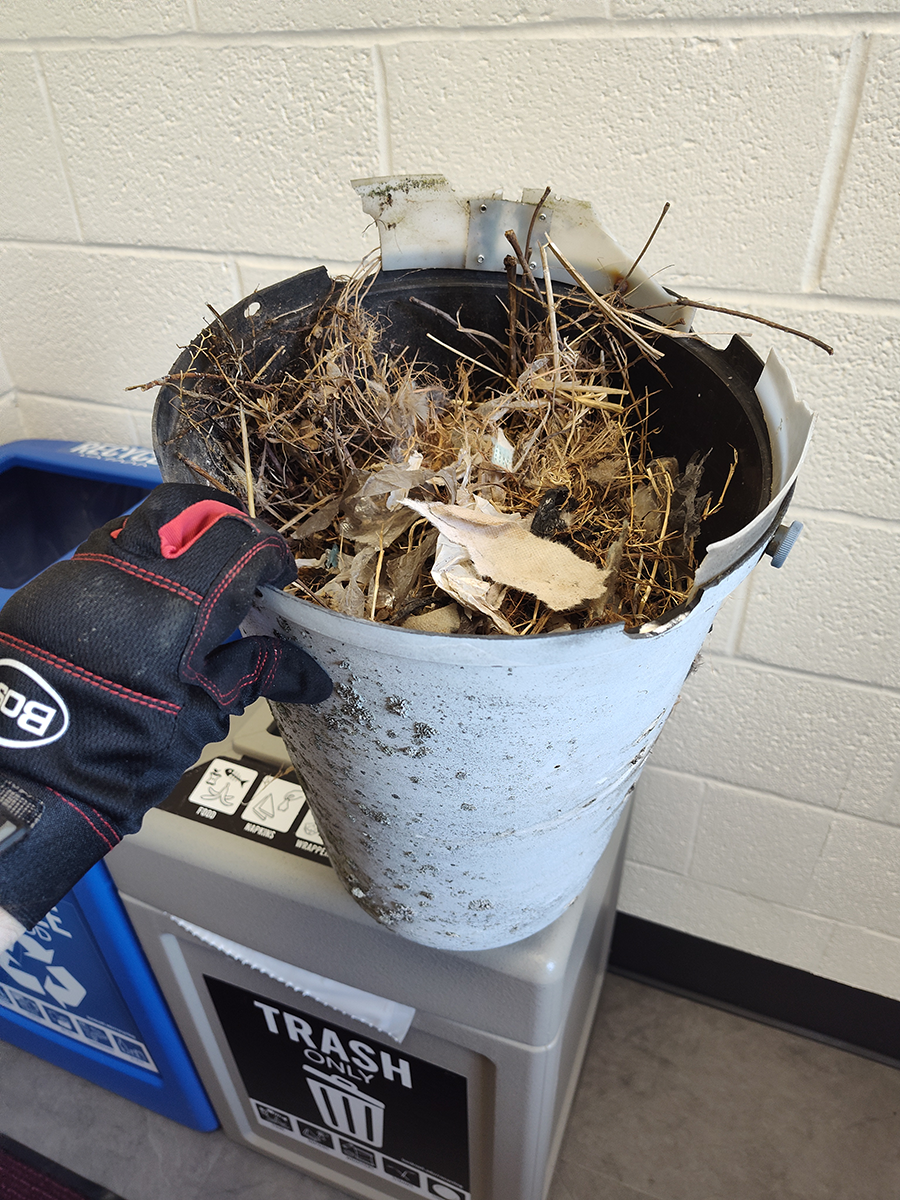

And they’ve built an astounding nest inside. Dried grass, last year’s hydrangea blooms, torn bits of plastic bags, some shredded paper, a few ripped-up bits of surgical masks. Removing all of this did not endear us to the starlings.

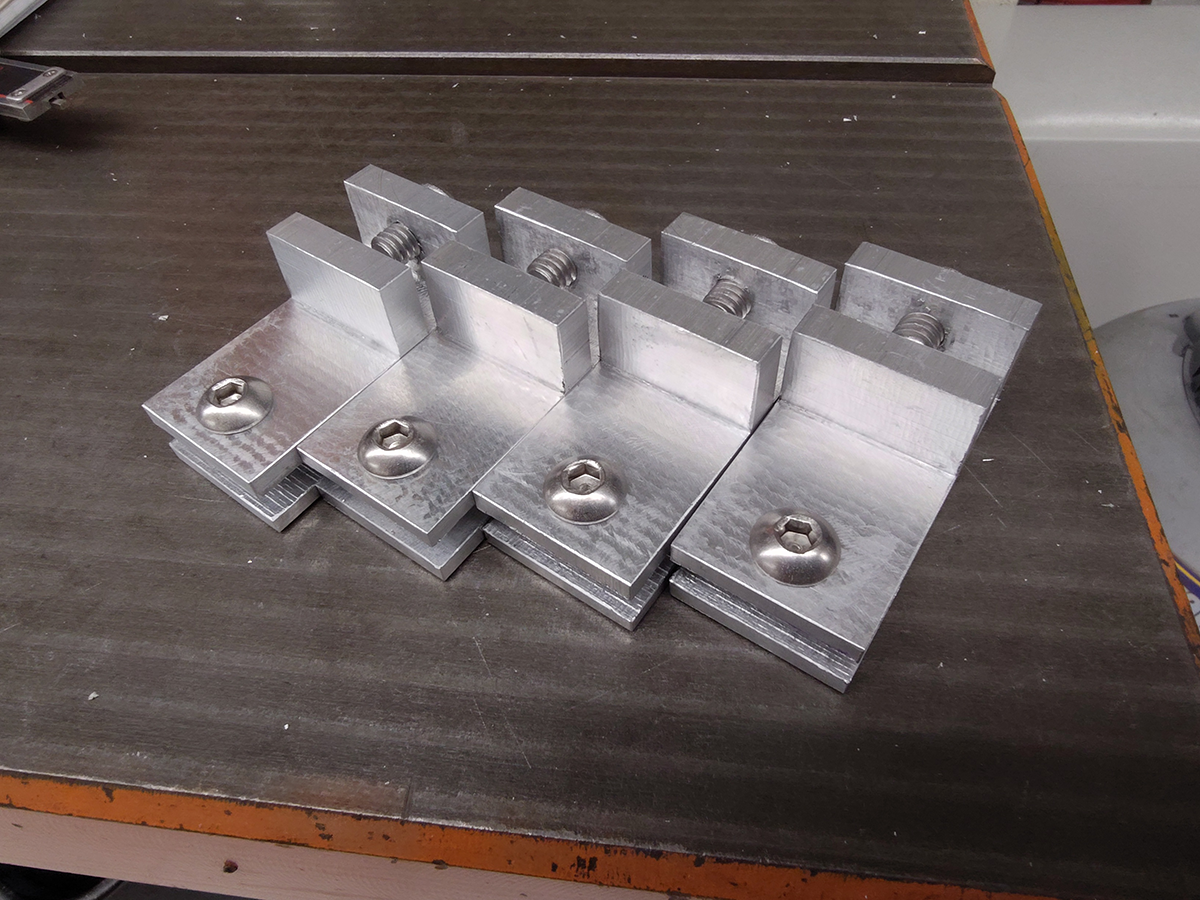

The plastic solution worked for a while, but it’s time to up our game. Aluminum brackets, precisely machined out of solid blocks, drilled and tapped for stainless steel hardware. Bright and shiny and destined to be hidden away from view.

And then, with summery Pennsylvania weather on the horizon (read: thunderstorms), we seal the whole mess up with duct tape. Maybe it’ll deter the birds until we can deal with the rest of it some fall.

The most amazing part is that we didn’t end up using hot glue.

Six decades ago, there wasn’t much on the south end of campus, making it an ideal place for the new Observatory. Relatively calm, not much to block the view, and few sources of nearby light pollution. A lot can change in that time.

Today’s maples and oaks – not pictured, because they were maybe saplings? – are now large enough that they block some low areas of observation and are losing limbs due to disease and age. The stadium has been wreathed by parking lots and festooned with high-intensity lights. Campus buildings have crept southward, surrounding the site. Lewisburg and its surroundings have developed, installed more nighttime lighting, and the sky has grown brighter, obscuring more of the night sky.

Clouds, however: they’re here as much as they ever were. Oh, central Pennsylvania.

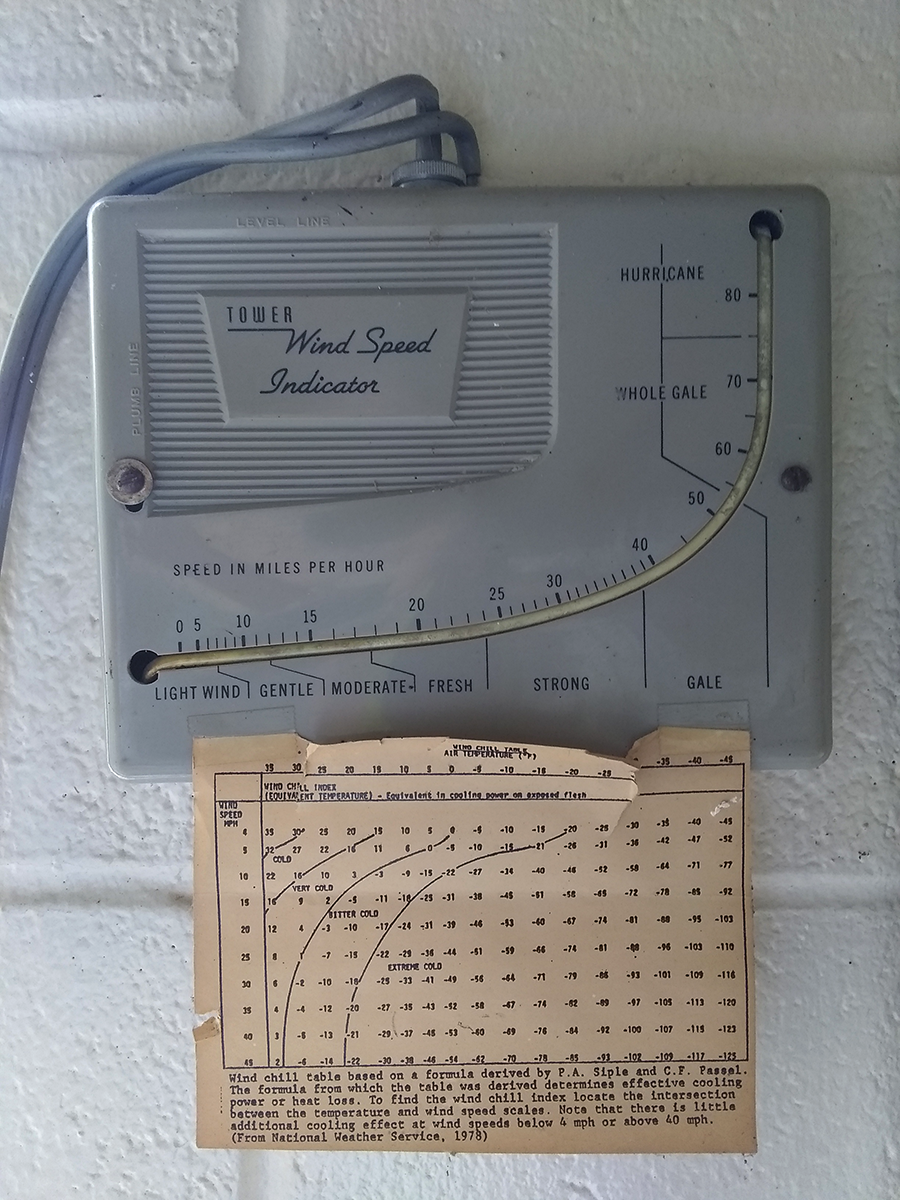

This particular wind speed indicator hasn’t been functional in ages, but at some point it was probably useful in determining whether or not to go outside for telescope observations. Wind is of concern in astronomy, as it can produce poor seeing and – when really strong – cause telescopes to shake. But wind chill is the more immediate concern. Cold nights can be good for observing, with clear skies and good seeing, but rough on fingers and toes.

All of that standing still, lack of warming sunshine, etc. doesn’t do a lot to counter a cold night. Maybe think ahead and bring along a hot beverage?

An awful lot of that chart is devoted to conditions when no one should be outside at all. One line of thought considers that a chart with all of your category indicators bunched up on the left isn’t the ideal for communicating information visually. Another notes that an endless tundra of negative numbers tells you enough without needing the particulars.

The Observatory’s windows have but a single sheet of glass, which leads to some impressive wintry displays when the temperature differential is just right.

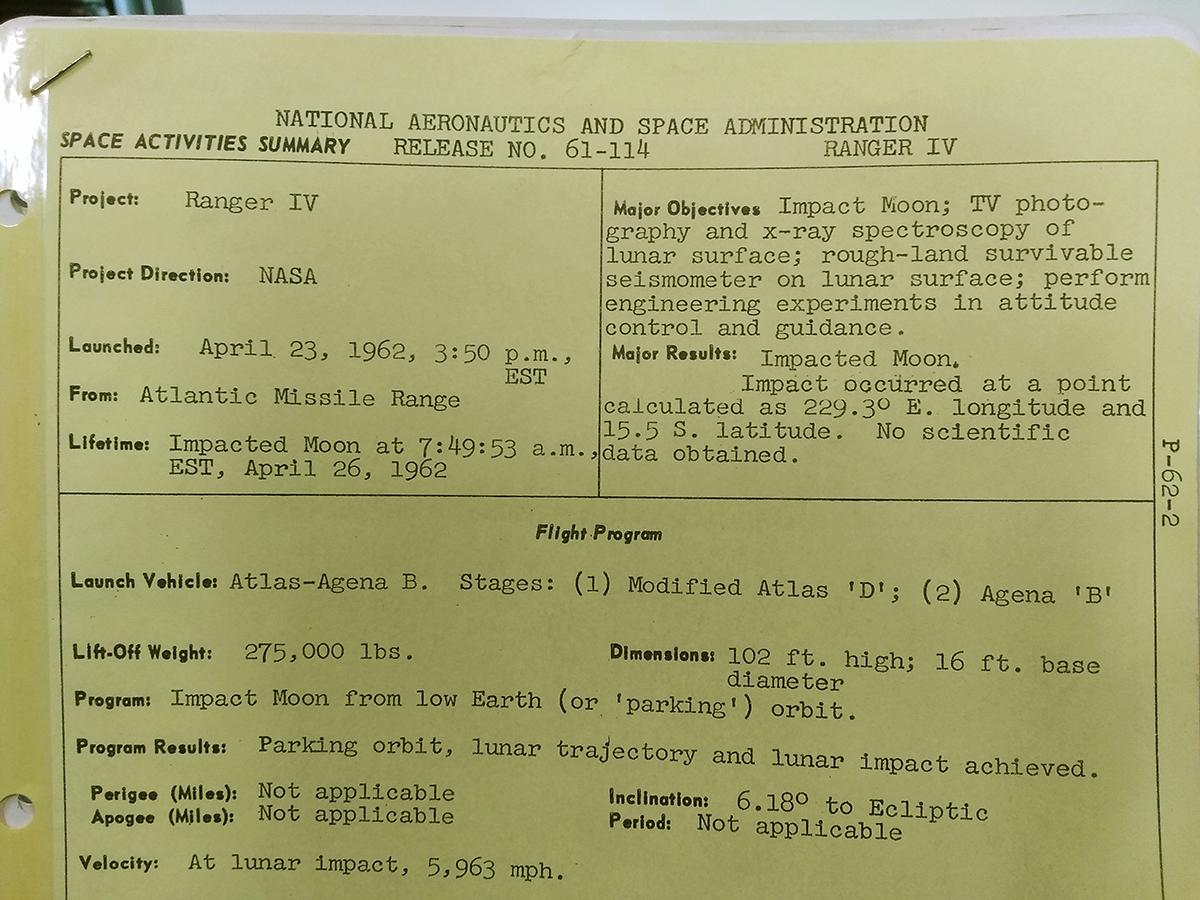

We have several boxes of NASA press releases from the height of the space age, for the simple reason that it’s easier to pack things away than to sort and dispose of junk. None of them are worth much, really, but they can be entertaining. Take this, for example, a summary of the Ranger 4 launch. Not mentioned here, but interesting: Ranger 4 was the first US spacecraft to reach another solar system body.

By crashing into the Moon, as intended. You can read more in a brief summary by Leonard David, or by skimming Wikipedia.

Entertaining bits gleaned from the Space Activities Summary:

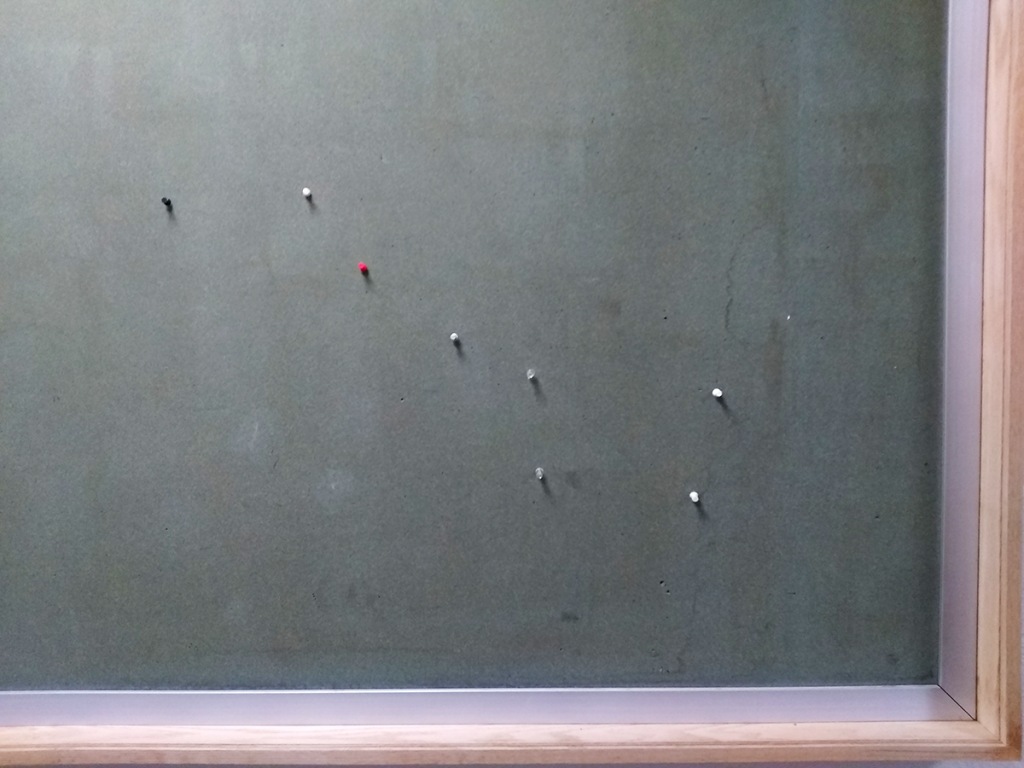

A surprise discovery on a hallway bulletin board at the Observatory: a push pin Big Dipper!

It’s good and charming and subtle, and we can forgive that this version has eight stars instead of the night sky’s seven. (Not counting the visual double of Mizar and Alcor where the handle kinks.) Someone did this on a whim, and now it’s hard to resist the idea of putting up others all over campus to see who notices.

Have a great semester break!

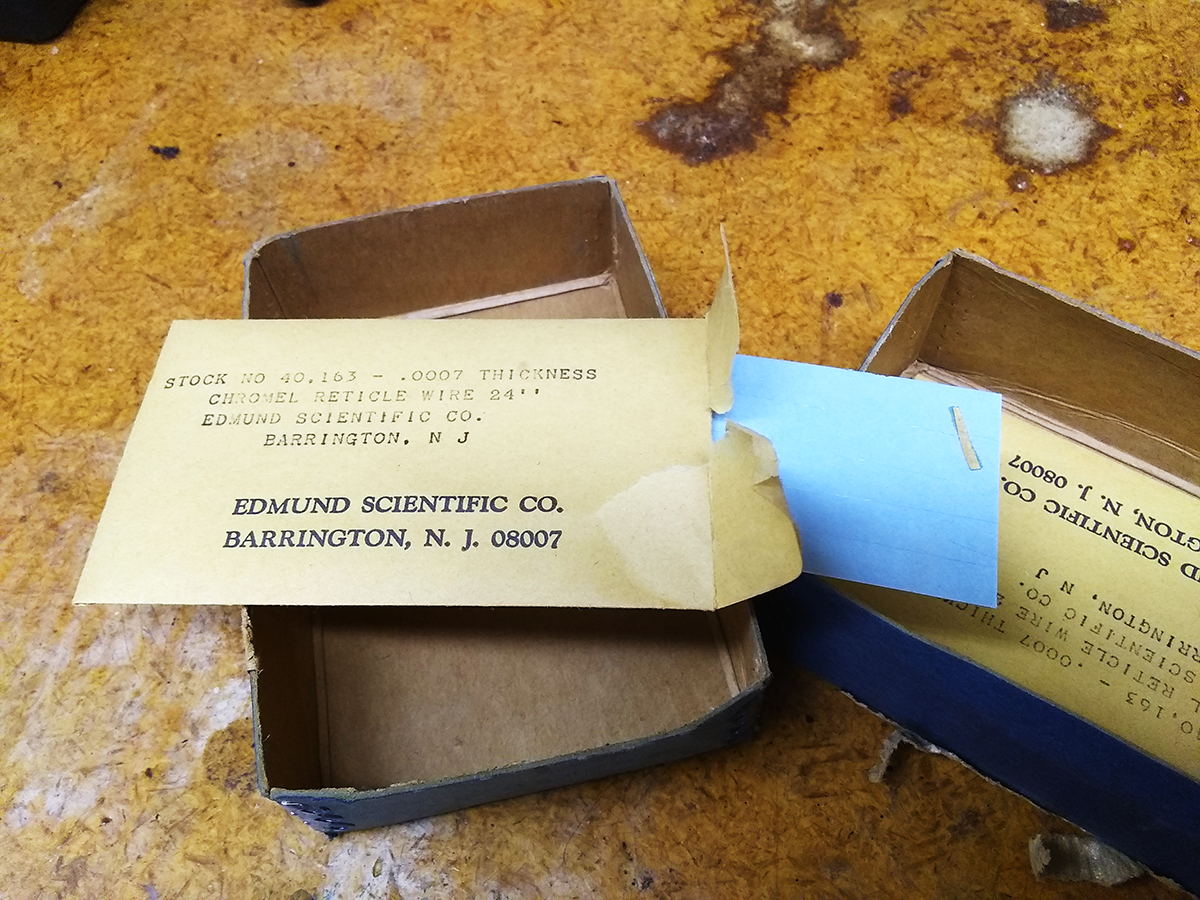

Making an ‘X’ across your telescope’s eyepiece is a handy thing, letting you mark the center instead of eyeballing it. There are all sorts of reasons you might appreciate that little bit of assistance, provided it doesn’t actively interfere with seeing things. So you use as fine a wire as you can. Which is going to break, of course, so keep some spares in the desk drawer.

How thin? This is AWG 53, all of 0.0007 inches thick (0.0178 mm). Enough to make even the finest human hair seem chunky in comparison.

Our Observatory is the second on campus, a replacement for the 1887 original. That one was constructed to house our antique Clark refractor telescope, an early gift from William Bucknell, because it’s really not the sort of instrument you set up on the front lawn when the skies are looking decent.

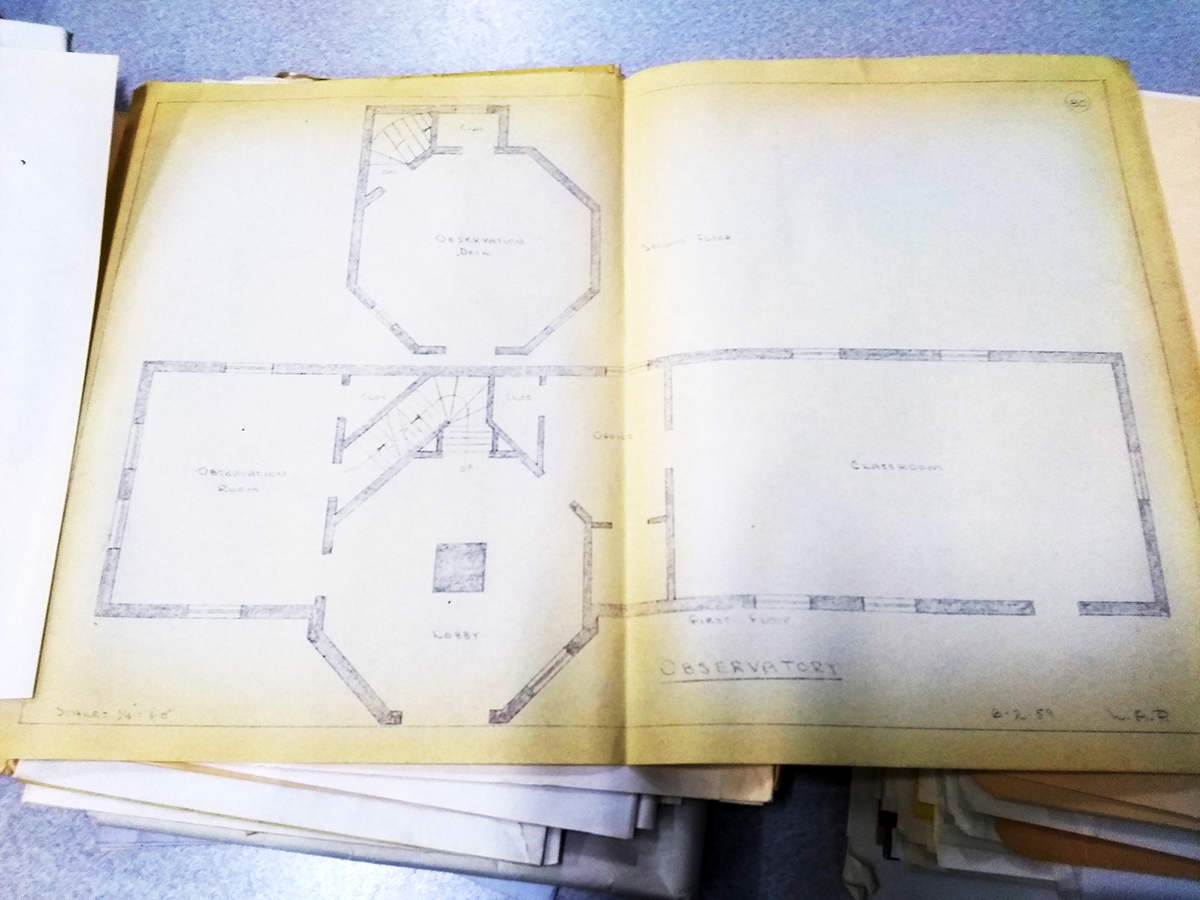

Here we see the building’s layout as of June, 1959, presumably as discussions were underway regarding the renovations that would begin in 1962. During which one of these walls would collapse, necessitating a relatively hasty pivot to create the current Observatory to maintain the astronomy program. (We’re very grateful for that, sixty years later.)

Should we expect restrooms in an 1889 structure? Which way is north? Did the individual drafting up these plans just not like drawing doors? What’s that unlabeled space “south” of the office? When transitioning a class from the classroom to the observation dome upstairs, do you lead the students through your office or make them go outside? So many questions.

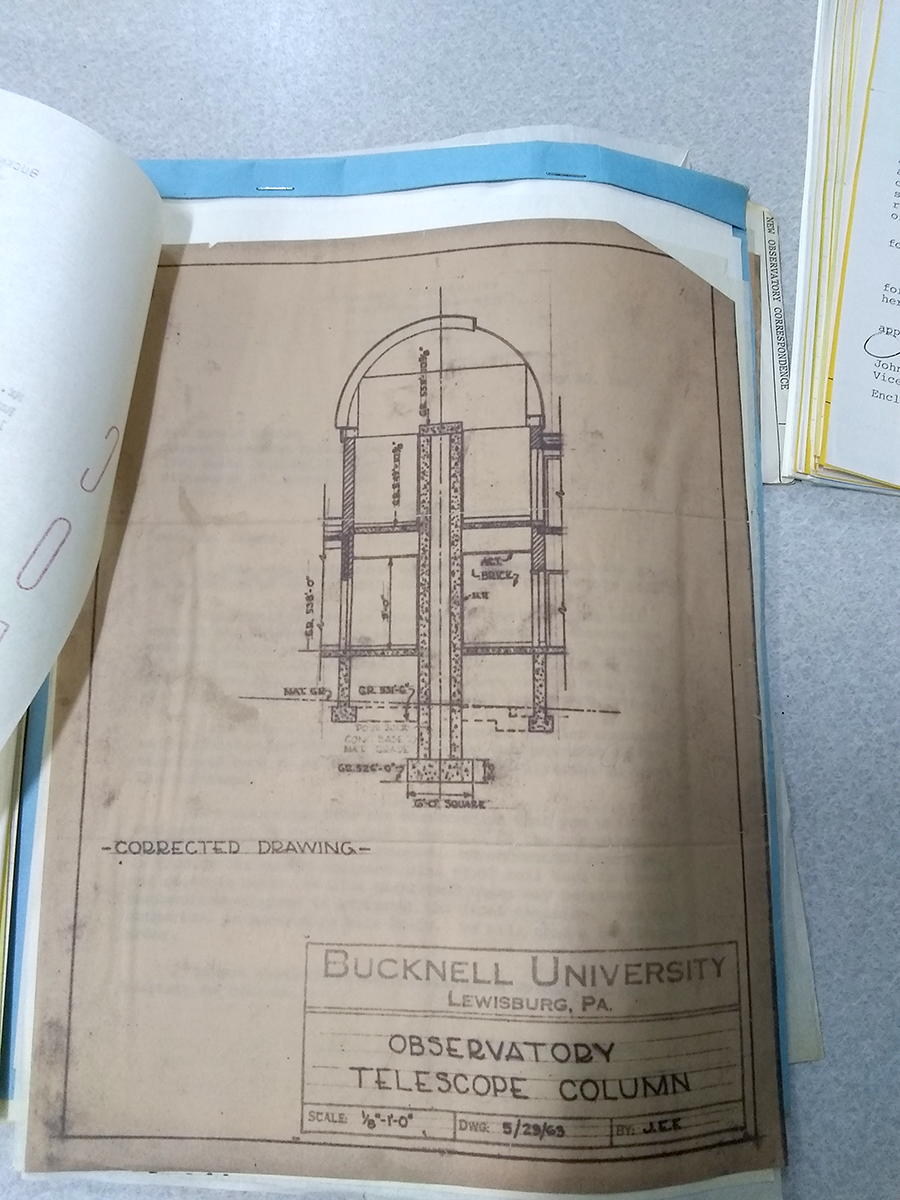

Our wonderful Clark refracting telescope support column, in all its masonry glory. Structurally isolated from the rest of the building so that footsteps don’t cause wobbles in the telescope’s field of view.

Sometimes, it’s the little things.