For the most part, the light accumulation of dust, pollen, and other stuff on the objective lens of your telescope is a thing you live with and ignore. The damage you can do to the lens and its optical coatings is far more severe than the minor loss of image quality from tiny flecks. Known and accepted trade-off.

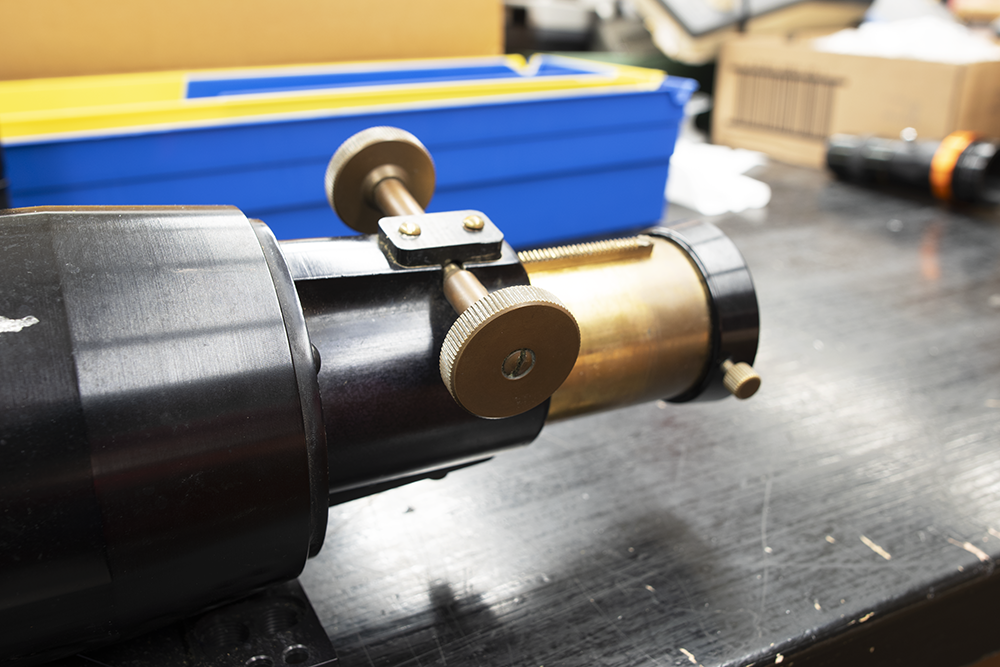

Here, however, we have a classic TeleVue Renaissance that’s still in good shape. Aside from the dust and dead spiders, anyway. Exact age is unclear, but we can roughly place it between TeleVue’s founding in 1977 and the construction of the “Halley’s Comet” models in 1985. Serial number 1100, for anyone keeping track at home. Even dust-covered, the optics appear good at a quick glance, and they have a reputation for remaining in good shape for a long time.

There’s a bit of chromatic aberration when you look closely, an issue which has been resolved in their current models. (Optics = hard.) The design type is called a Nagler-Petzval, which uses a pair of lens doublets to correct numerous distortions caused by refraction. Every design has its pros and cons; this one’s quite nice. Our version has – we think – an air-spaced doublet (two lenses utilizing different curvatures) as the objective, and a cemented doublet in the rear.

At least, that how the Halley’s Comet edition was made. The current optics update utilizes two air-spaced doublets – see the diagram for the NP101is – so it’s reassuring to see that the improvements are incremental. Good sign for the one we have.

Okay, the brass could’ve aged better, but it’s got character!

Black on brass looks good.

Even the knurled knobs on the focuser are brass. We don’t want to leave this for display, however. We want to see the stars!

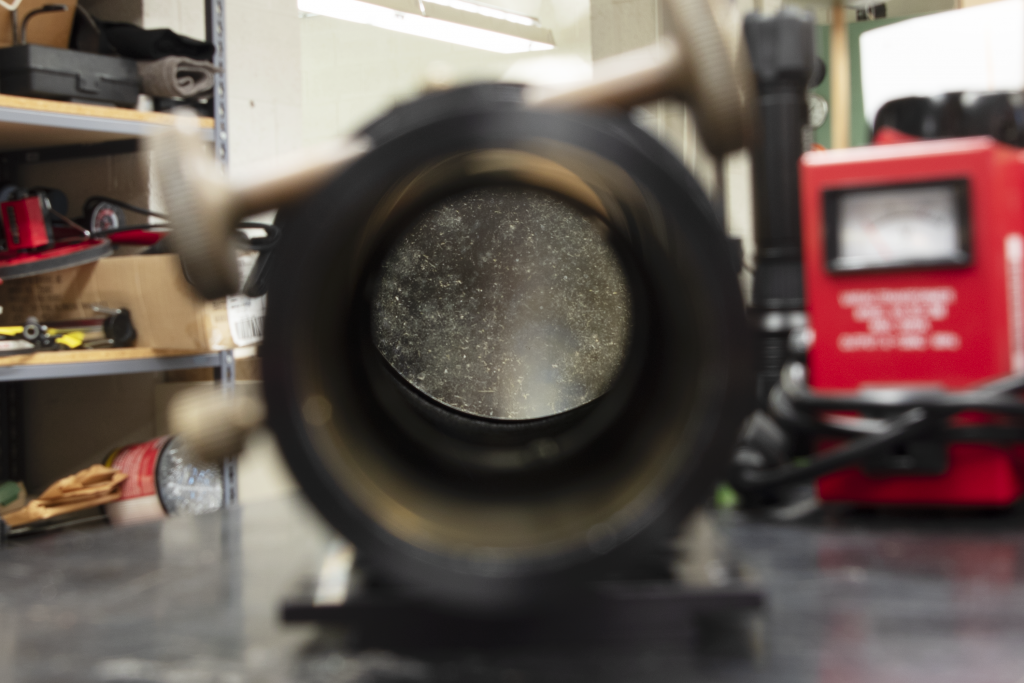

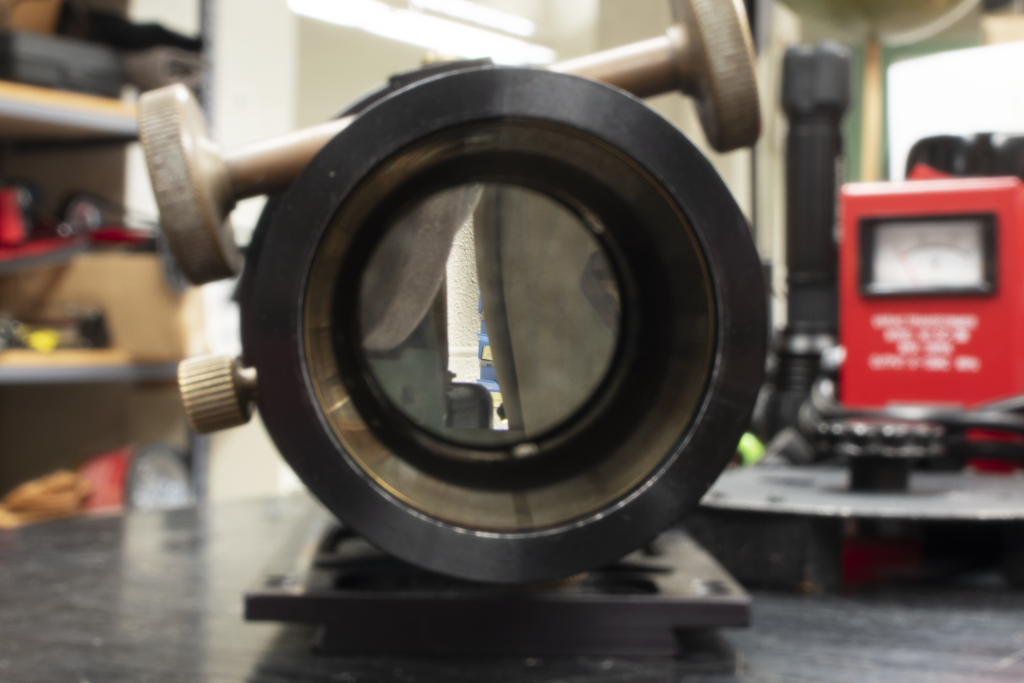

That dust, though.

Yeah, definitely a problem. A cleaning is in order.

Not pictured: the dead spiders removed with air from a bulb blower. Dead spiders do not improve optical quality.

Here, we’re applying a coat of First Contact polymer cleaner, an expensive but effective treatment for safely removing gunk from precision optics. Comes in a wee bottle like it’s nail polish and smell like nail polish remover. Because it’s got acetone and other solvents in it.

Once it dries, that little tab lets us pull away the pink film with all of the dust and debris stuck in it. A good time to wander away from the stink of volatile solvents and get a cup of coffee.

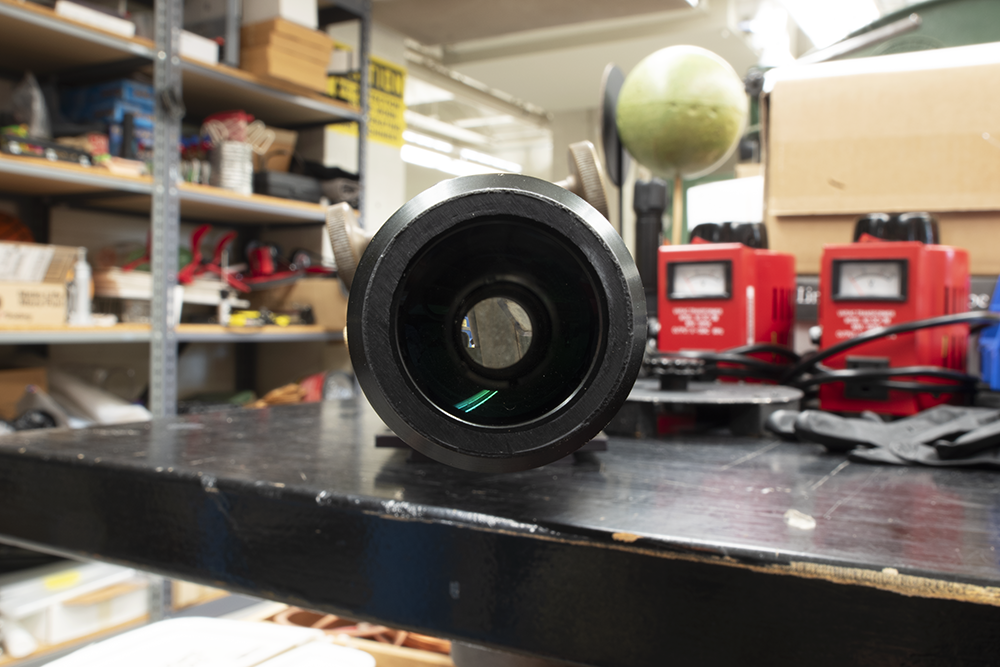

And, well, that’s a substantial improvement.

It’s not perfect. The polymer is very good at removing particulates, but less so at water-soluble stuff. Once we evaluate this with a camera setup, we can see if a follow-up cleaning with deionized water is necessary.

Problem there, of course, is that we run the risk of introducing tiny scratches in the process. Could be worthwhile if the effects are still visible, but we’re still erring on the “do a minimum of harm” side of things.

Will it live up to its potential as an imaging ‘scope? Maybe. There’s a fair chance. If not, we’ll keep it around as a stylish yet usable throwback for visual observation. The best telescope, as they say, is the one you use.