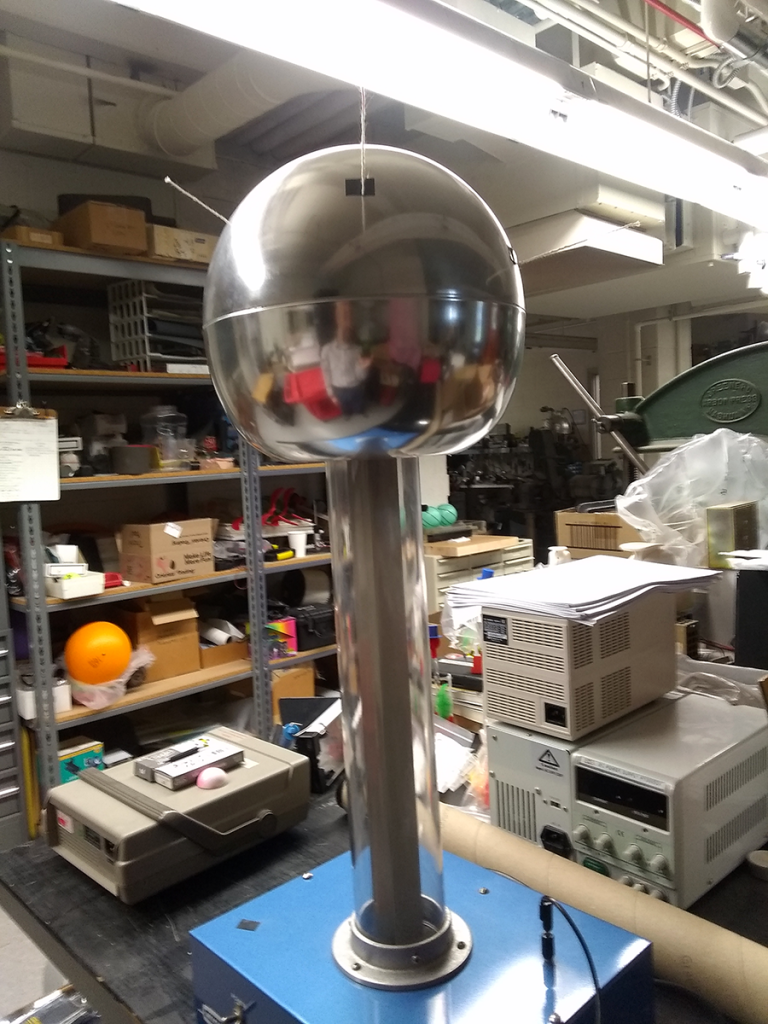

The spring semester PHYS 212 course starts with electrostatics, and what could be more entertaining than a Van de Graaff generator? A whirring rubber belt on two different rollers – one acrylic, the other covered in dense wool – builds up an electric charge on the anodized aluminum dome. The air positively crackles, and the discharge arcs look pretty great in a dark room.

Plus, it makes your skin feel all weird if you get close but not too close.