Tools undergo a great deal of stress in doing their job. They wear down, dulling their edges. There are impacts, intended and not. There’s a lot of force, and heat, and effort in shaping raw materials into something more useful. Tools are generally made from hard materials, intentionally harder than the material they’re working. Harder materials, broadly speaking, are more brittle.

So they’re good, they’re good, they’re good… oops. Broken.

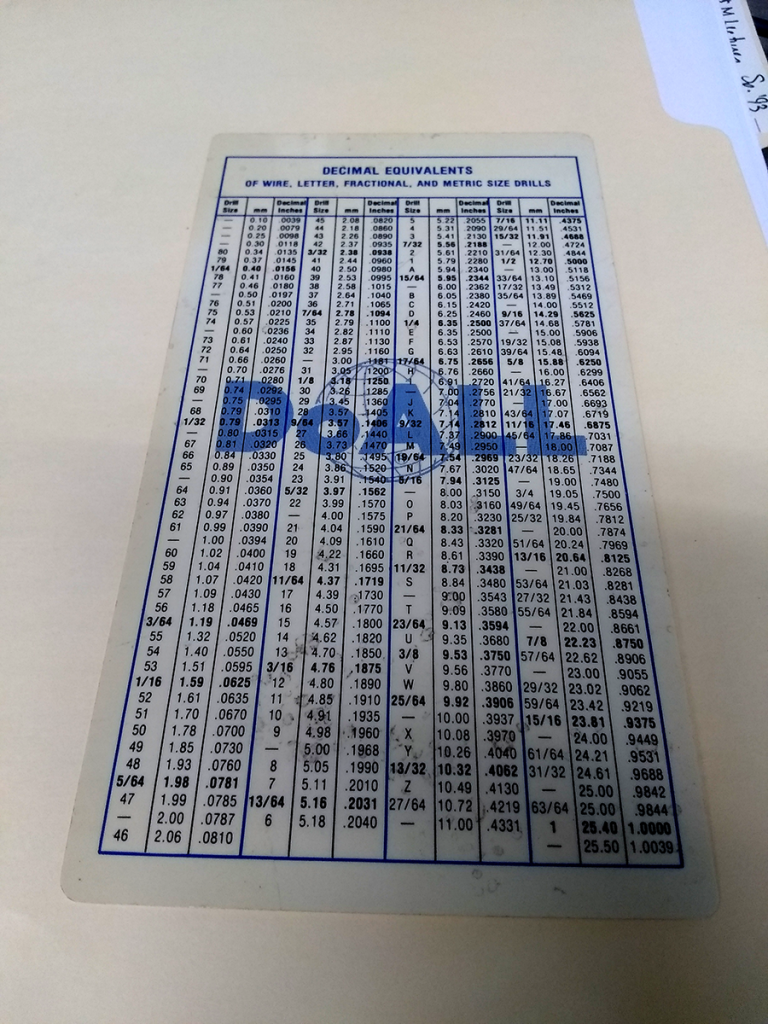

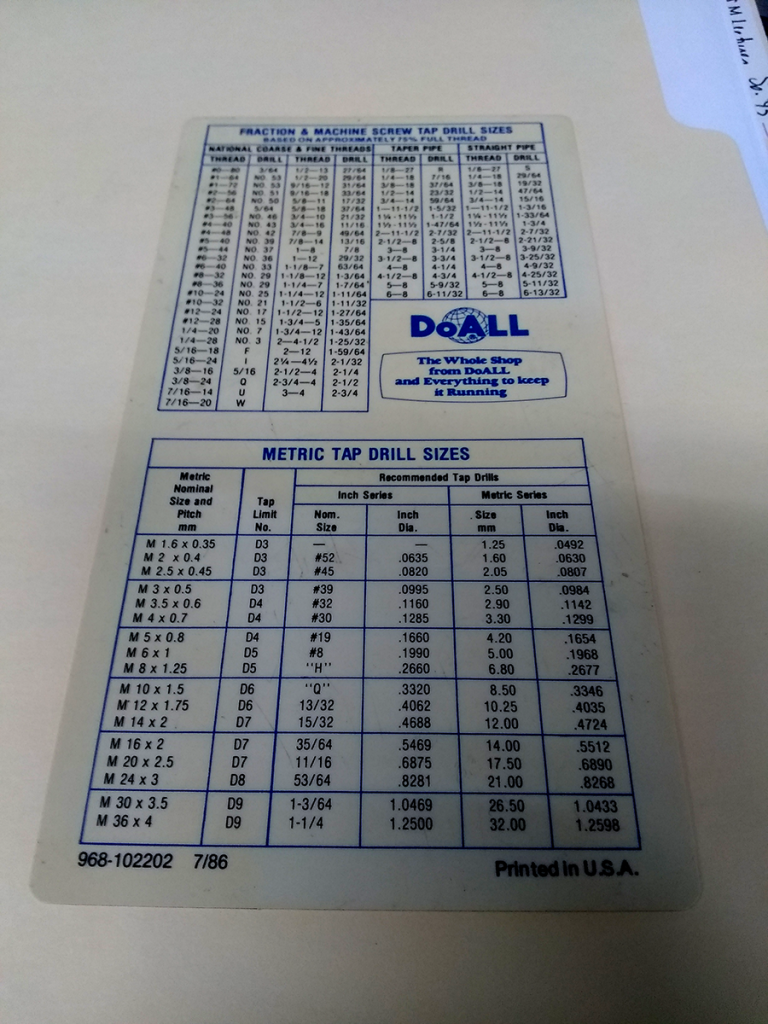

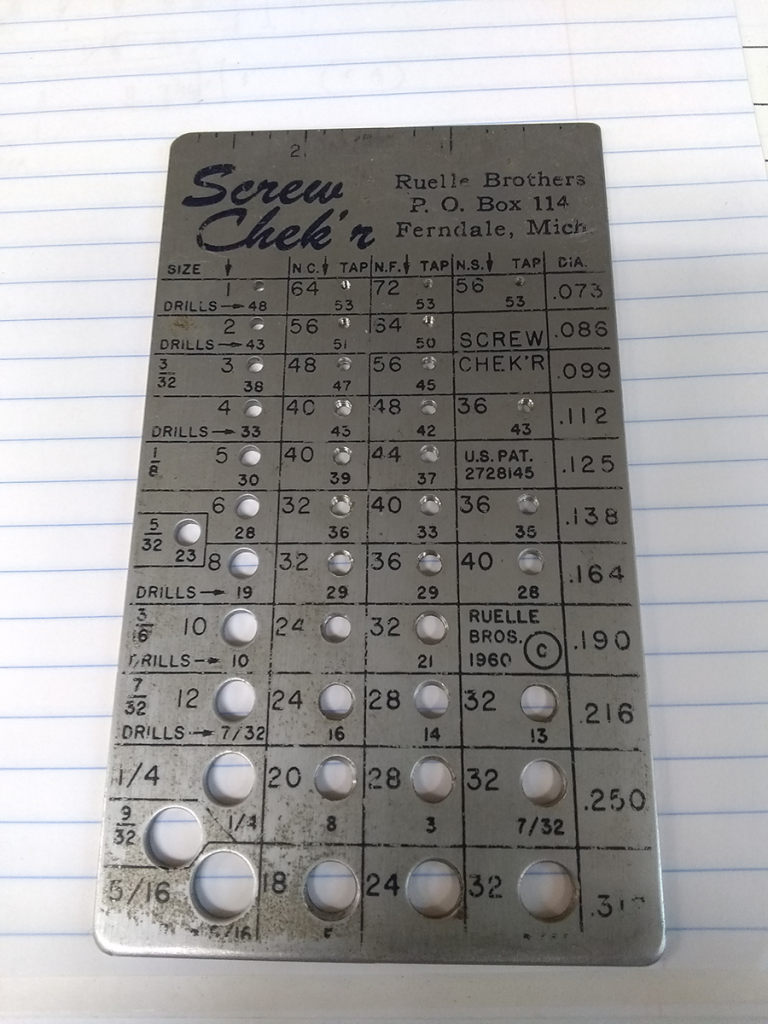

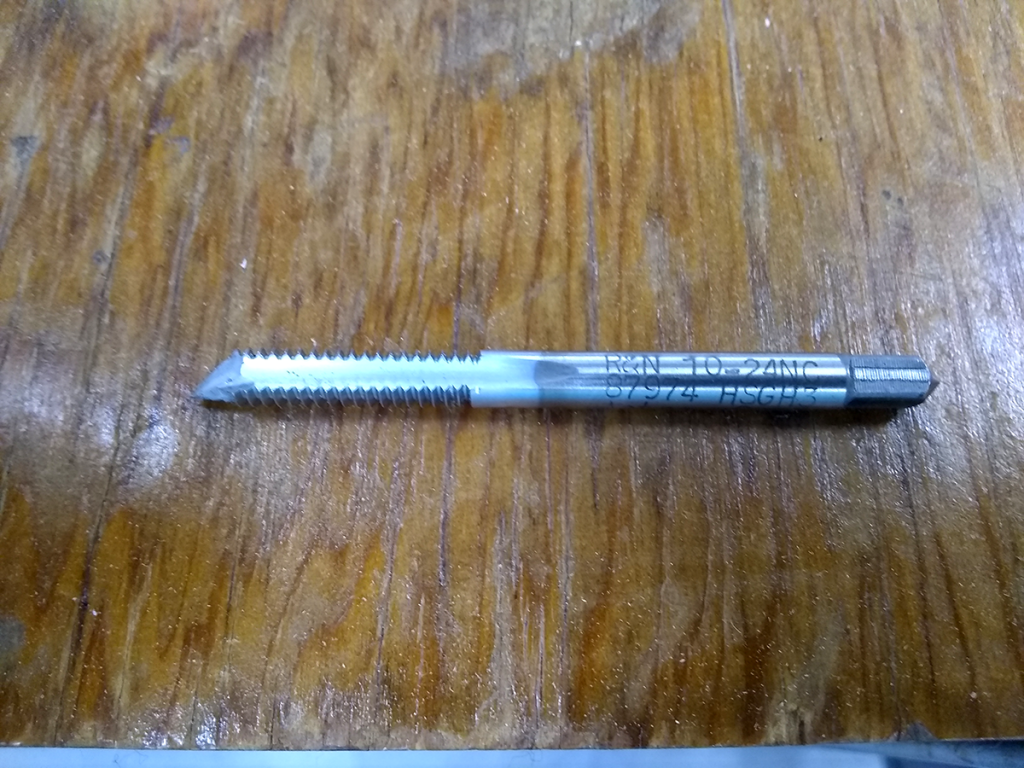

A lot of the shop’s milling and milling-adjacent tools are made of high-speed steel (HSS), a group of steel alloys which perform well at high temperatures without losing their temper. Tungsten carbide (often called carbide) is even harder, and we save those for jobs that need it. Carbide’s brittle enough that it can’t be used in hand tools, instead requiring a sturdier, rigid setup like a milling machine, a drill press, or even better, a CNC machine.

They’re awfully expensive to replace.

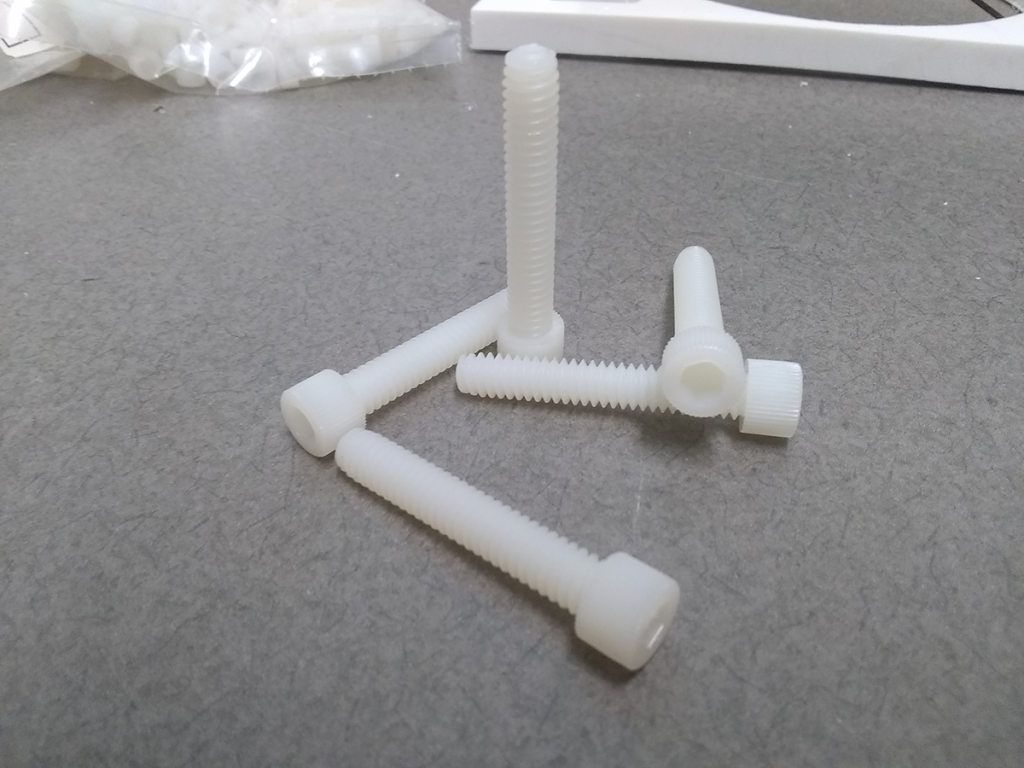

Some tools, though, require human hands and a deft touch. Taps are one such example. The action of cutting threads takes firm yet gentle pressure, with frequent pauses and reversals. The tap gets hot; the material gets hot. The corresponding thermal expansion makes the tap more and more difficult to turn, increasing the risk of fracture. Best be patient.

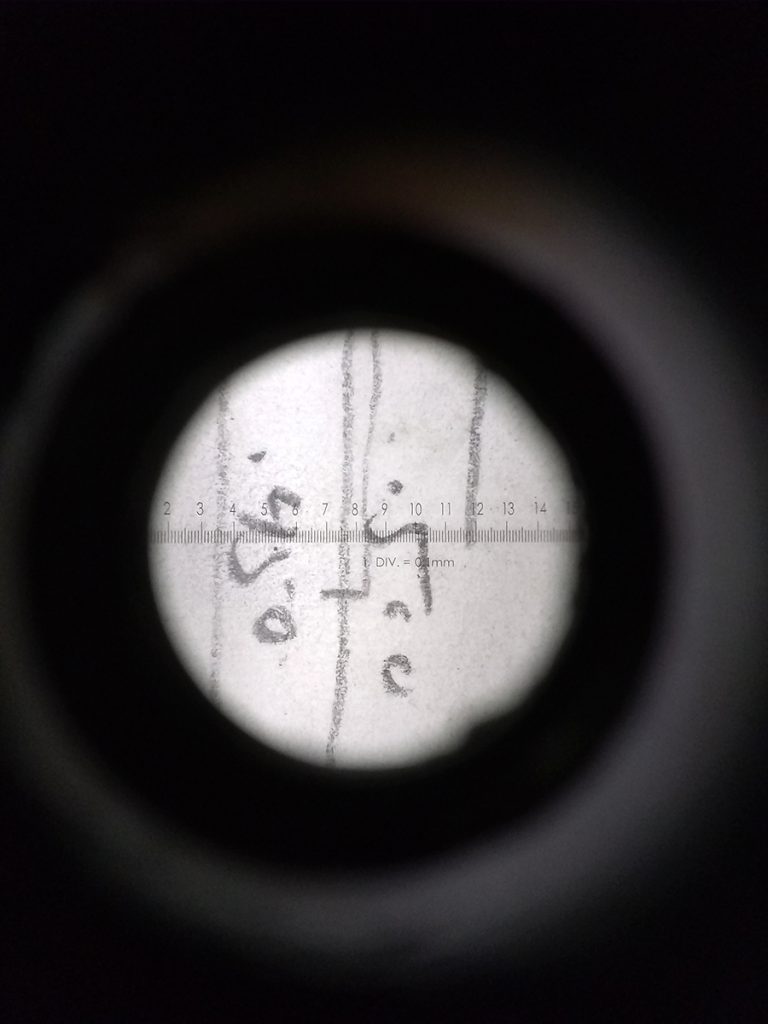

And sometimes, despite all that effort? The high-pitched *tink* that tells you the tap snapped. It’s subtly different from the similar sound that a curled, not-yet-removed burr of metal makes when the tap runs up against it. Sigh.

Reverse the tap, slowly, carefully. See if you can remove the broken piece without damaging the hole. Remember that it’s harder than the material it’s in, and probably as hard as the drill bit you’d like to use to dislodge it. If need be, drill a new hole and try again. This particular tap met its end putting threads into cast iron, a less-than-ideal material for most of our machining jobs.

Mistakes. They happen.