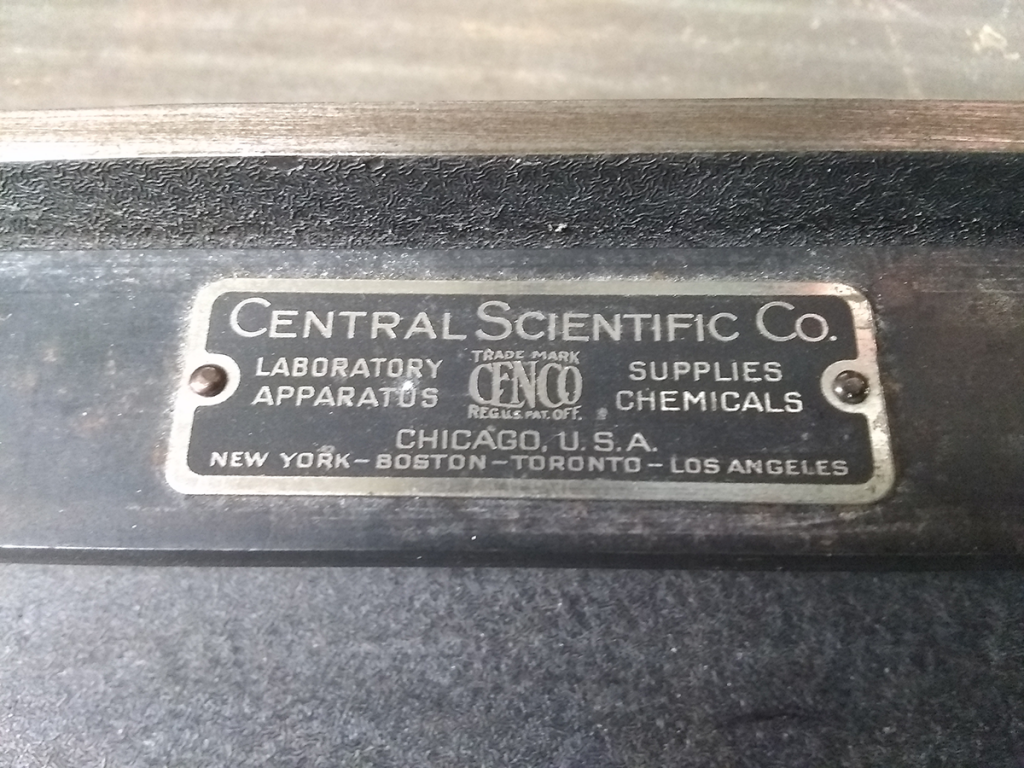

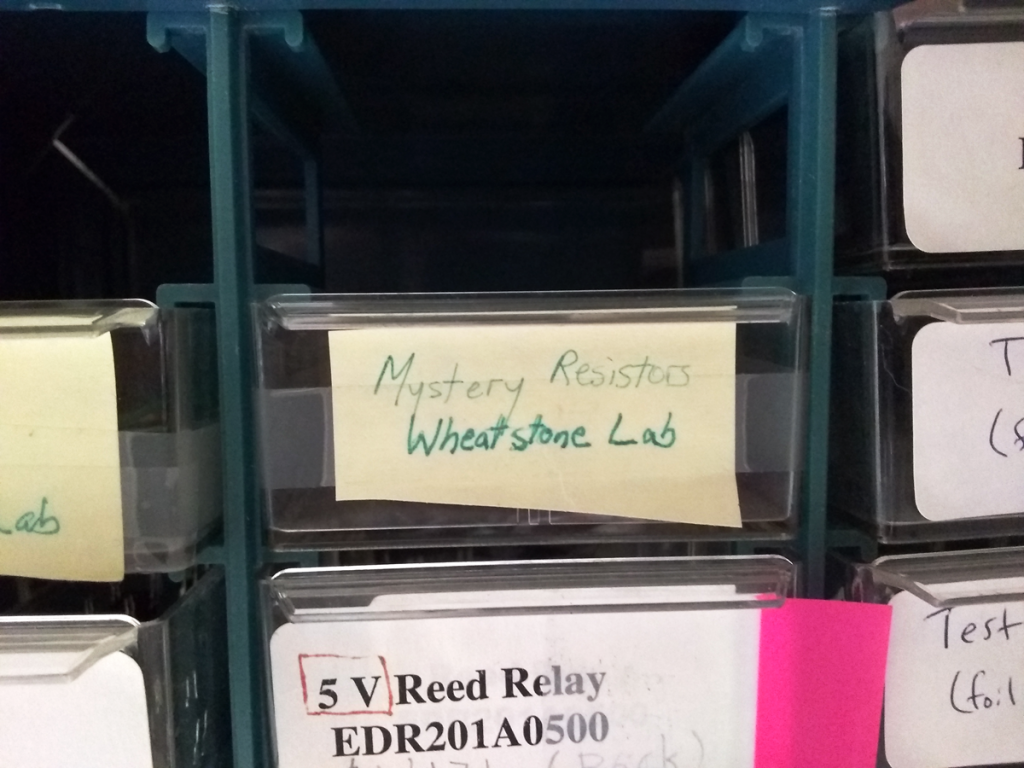

One of the many entertaining quirks of an academic setting is the need to organize certain things to conceal their specific nature. When running student labs, it’s not uncommon to give them something to measure using the theory and techniques they’ve recently learned. The instructor knows the approximate Ohm value of the resistor, but the students need to construct a Wheatstone bridge and measure it, because we’ve cleverly concealed the color markings with tape, or permanent marker, or shrink-wrap tubing. Whatever it takes.

Then it goes into a little bin with an entertaining label like MYSTERY RESISTORS! and we get a bit of minor entertainment every time we walk by.

MYSTERY!