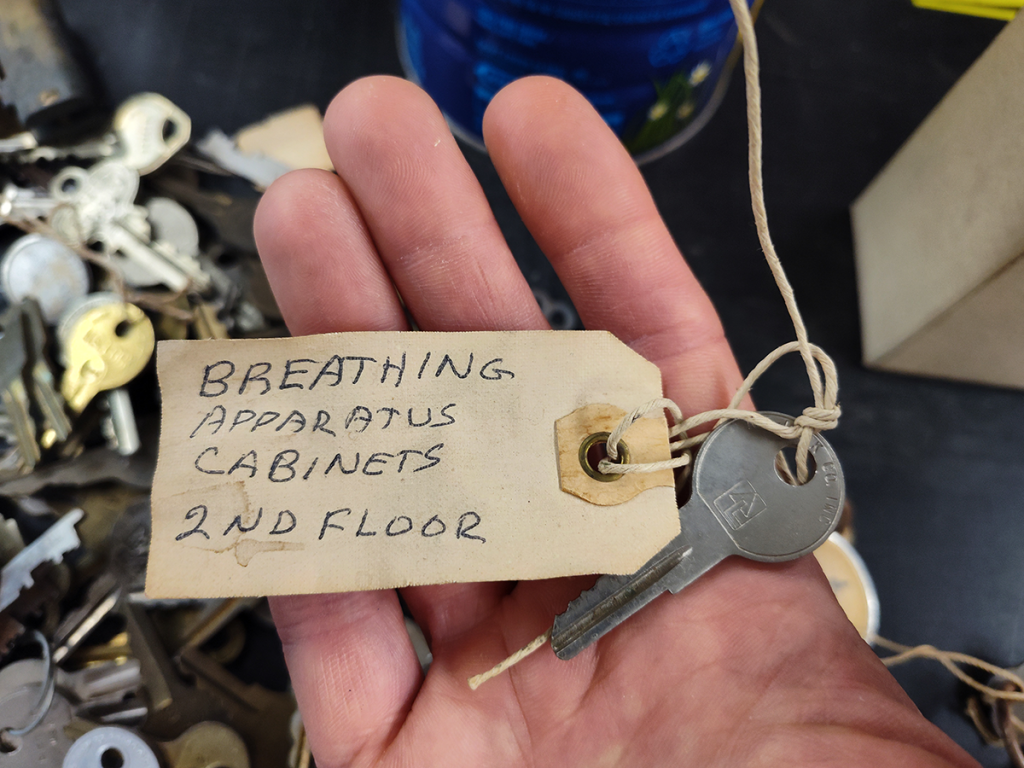

“Classroom door key.” Matter-of-fact, handwritten on a torn adhesive label. No need for building or specific room number identification. (The other side has no markings.)

Maybe there was only one classroom at the time? Maybe they were all keyed identically? Maybe the original bearer was only concerned with one specific classroom, one which needed no elaboration? Who knows?