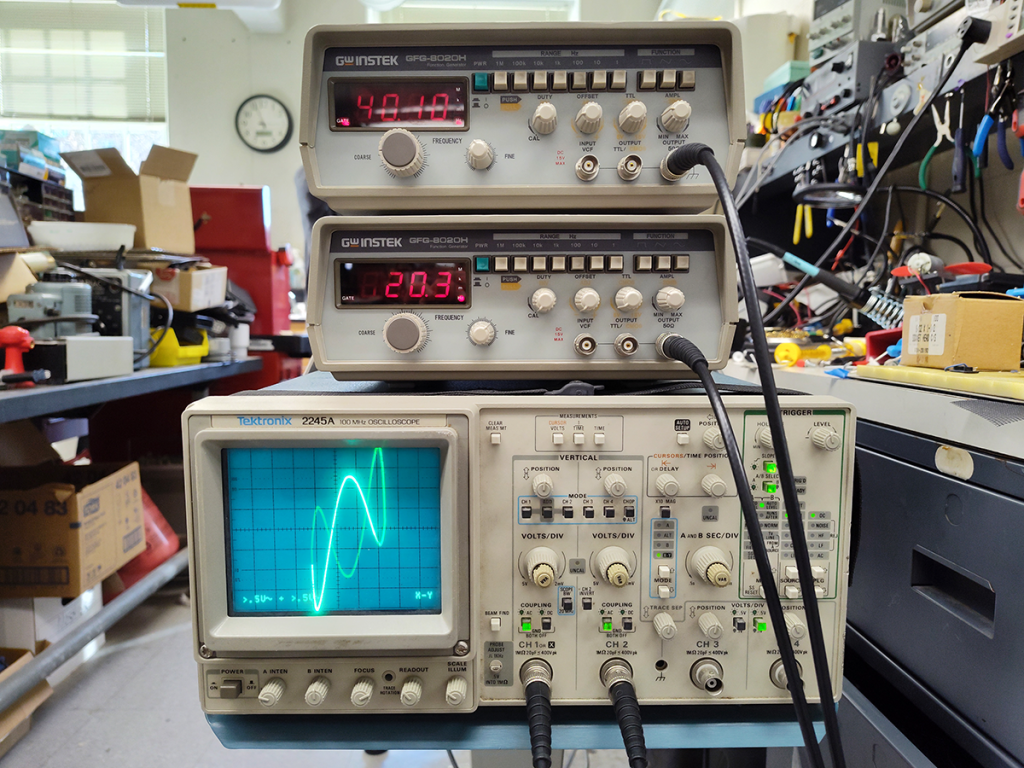

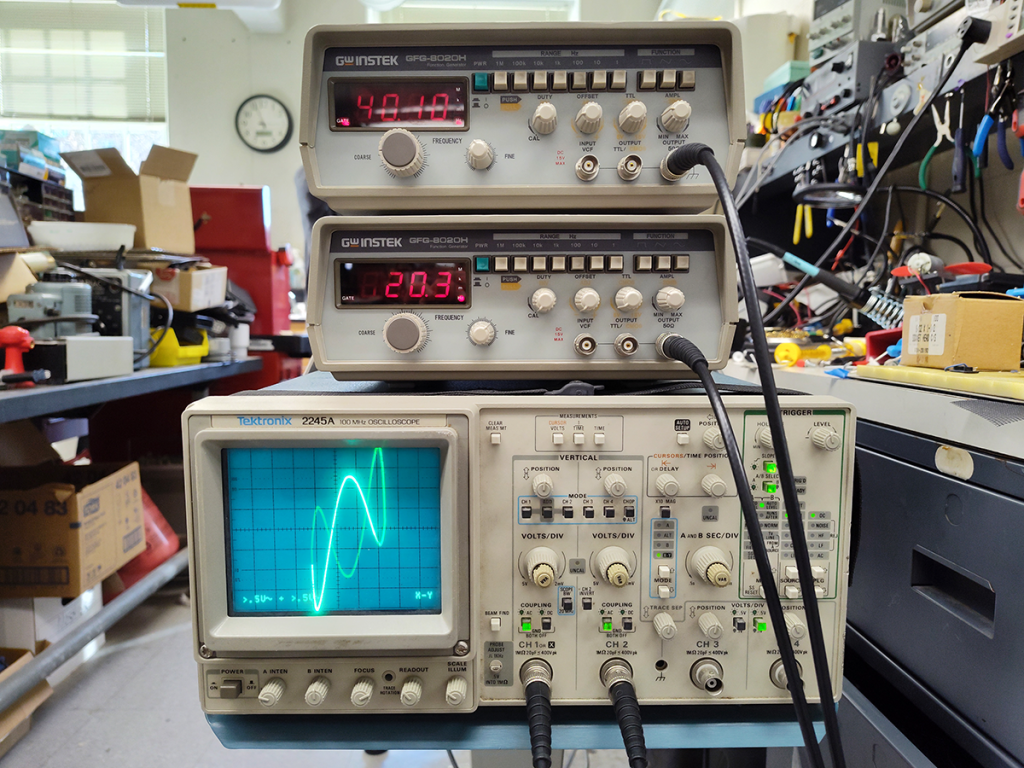

Take two function generators, an old CRT oscilloscope, a couple of power and BNC cables, and look! Whirling, dancing lissajous figures!

Chunky knobs! Clicky buttons! Drifty outputs! Squiggly curves!

Discoveries in the Physics & Astronomy shop | Science, curiosities, and surprises

Take two function generators, an old CRT oscilloscope, a couple of power and BNC cables, and look! Whirling, dancing lissajous figures!

Chunky knobs! Clicky buttons! Drifty outputs! Squiggly curves!

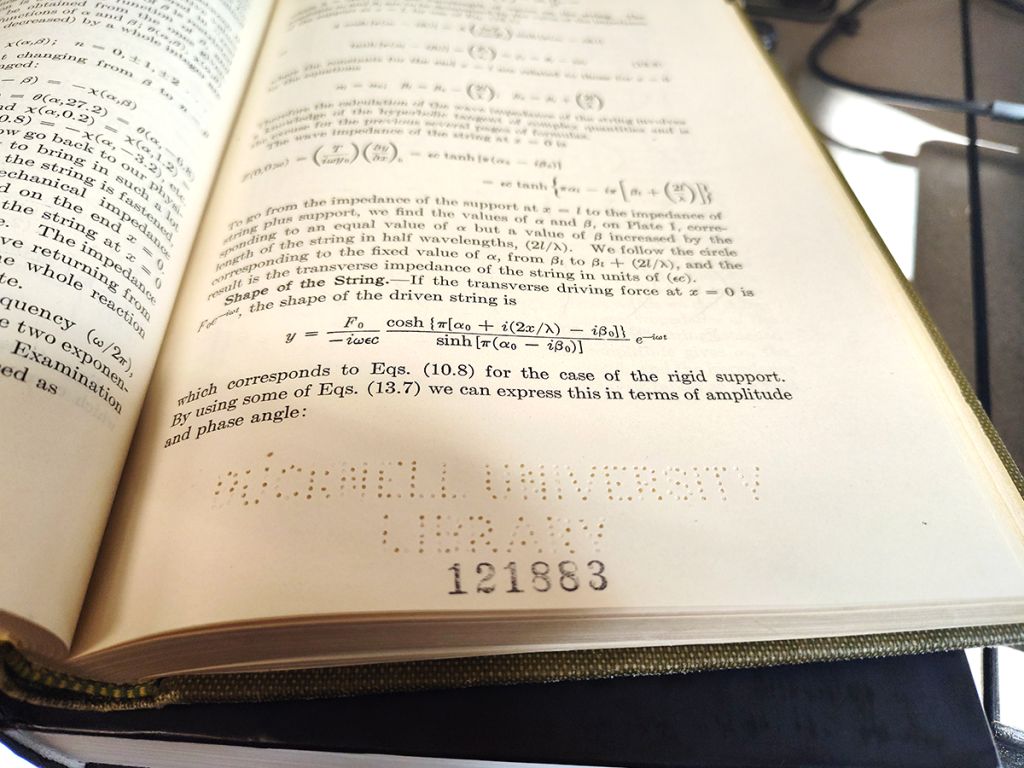

Old texts from the library sometimes still have these perforated markings, ensuring that no one forgets that this particular copy of Morse’s Vibration and Sound, from the International Series in Pure and Applied Physics, isn’t the same one that Grandma’s reading for her book club. They’re kind of charming in their own way, a means of labeling texts that disappeared at some point.

Presumably the librarians could enlighten us on that point, were we to ask nicely.

In the meantime, we’ll just muse over the idea that for a time, some individual had to take every new acquisition and punch a few of these before the first shelving. Some dedicated machine sat on a desk just for this purpose. And when it was a big day, those little punched-out chads probably got everywhere. The spilled glitter of their day.

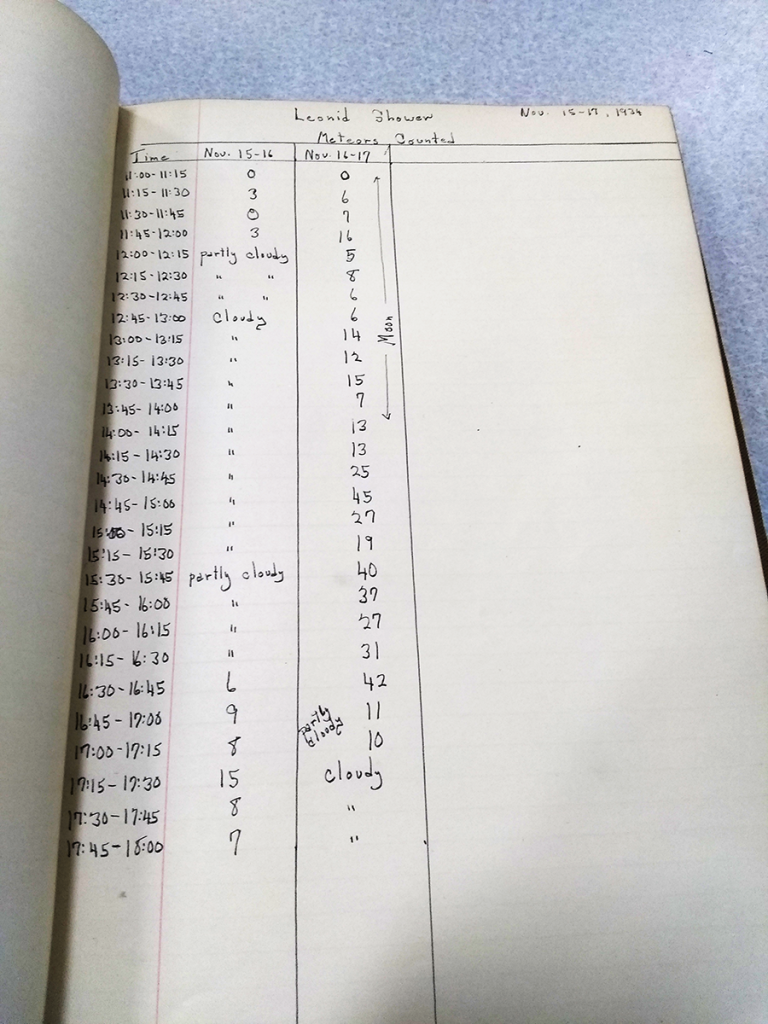

Ninety years ago, during the Leonids meteor shower, someone was counting a lot of burning bits of debris from comet 55P/Tempel-Tuttle. With one fifteen-minute window boasting forty-five meteors (!), that’s a powerfully active shower. Not quite a storm, but those happen with the Leonids sometimes.

According to NASA, the Leonids peak about every 33 years, with 1966 being a spectacular meteor storm. In one fifteen-minute window, thousands of meteors fell like glowing rain. How amazing is that?

Also: check out the times indicated. We’re assuming the counting started at 11:00pm and ran until early morning, with a 24-hour clock opposite how we’d expect it. (Maybe sleep deprivation?) Either that or it was a truly spectacular meteor shower!

In our Physics & Astronomy labs, we use metersticks with great frequency. Often for measurements, sometimes to approximate distances that make the arithmetic easier, and occasionally as a handy tool for pointing to the projector screen.

They aren’t super-high precision any more than the rulers you remember from elementary school, and for that we have other tools. Sometimes, as you can see above, the years have warped and twisted things a bit. We adjust.

As you might expect, they offer metric distances on one side, inches and feet on the other. The best ones – the oldest set – were long ago painted black to conceal those SAE units. Clearly, someone grew weary of students measuring everything in inches and then complaining that the math wasn’t working out right.

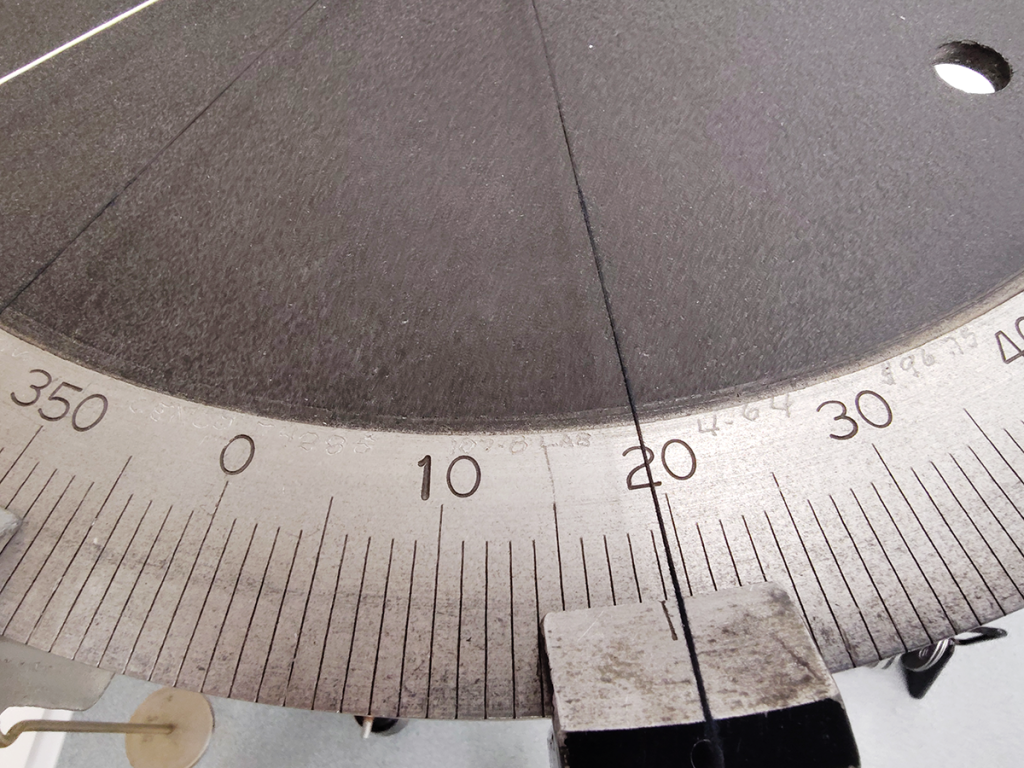

We’ve pointed out our old and reliable force tables before – classics of the undergraduate physics experience – which arrived here in several installments. Previously, 1957. This young’un only appeared in April of 1964, intended for the Physics 107-8 lab. Not listed in any recent course catalog, we’re uncertain of exactly what that was.

We could probably go pester some librarians, because surely there’s a record, but those folks are awfully busy on more important matters. Leave the idle wondering to the fellows here in the basement.

At any rate, they paid a healthy sum of $96.75 for this precision-machined beast. In today’s dollars: $985.65.

Do you think we’ve gotten our money’s worth yet?

First class postage as of January 27th, 1956 cost three cents.

At one point in time, the slide rule was an essential tool in a physics/math/engineering education. Built and etched with high precision, they enable a skilled user to perform all sorts of mathematical operations with speed and ease. It’s the power of logarithms in a hand-held device.

Which, if you’re the sort of person who can master a slide rule, means you can also fully grasp the particulars of how one works.

It’s a smidge harder to get there with an everyday calculator. The gulf between the solid-state electronics inside one and the button-pressing interface is enormous.

At one point in time, this beast was a handy demonstration device at the front of the lecture hall. Visible from way in the back, it lets an instructor illustrate proper slide rule use to an entire class at once.

Not that that happens much anymore, but this thing is awesome. If you found one back in the closet, you’d keep it handy, too.

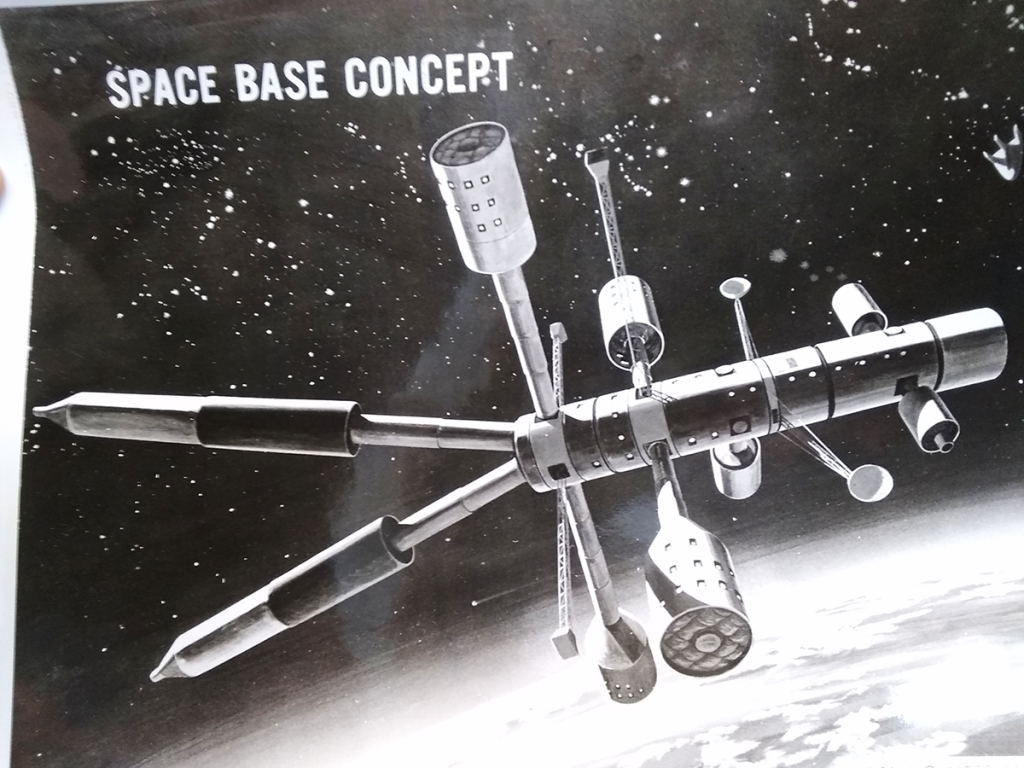

Sometimes you stumble across an old gem in the lost files and piles of forgotten stuff. Space base!

Remember slide film? Carousels and projectors and hauling out the big screen to see those vacation photos? Are you old enough to remember high school and/or college lectures on slides? The shop techs remember.

Nowadays everyone’s much more likely to use Slides than slides, of course. More portable, for the most part. Easier to edit, up until the last moment. Overall, a lot of advantages. But the old-school ones were pretty cool, too.

One can only hope that back in the days of the Audio-Visual Aids Department (we’re assuming they’ve been subsumed into L&IT, but not ruling out the possibility of a now-defunct academic department), they wheeled these – and film projectors, and VCRs, and hopefully LaserDiscs, too – into your classroom space on the classic steel cart. Embedded YouTube clips just aren’t the same.

Classic and simple, this wood and… leather-like chair has probably been in this office since the mid-20th century. Still in good shape! Nice curves, old-style rivets with a hammered finish, and a subdued brown-on-brown color palette. Sits comfortably.

Somehow, despite surviving the decades of use and age, a misaligned decal proclaiming “quality” gives one pause. Was it really that hard?