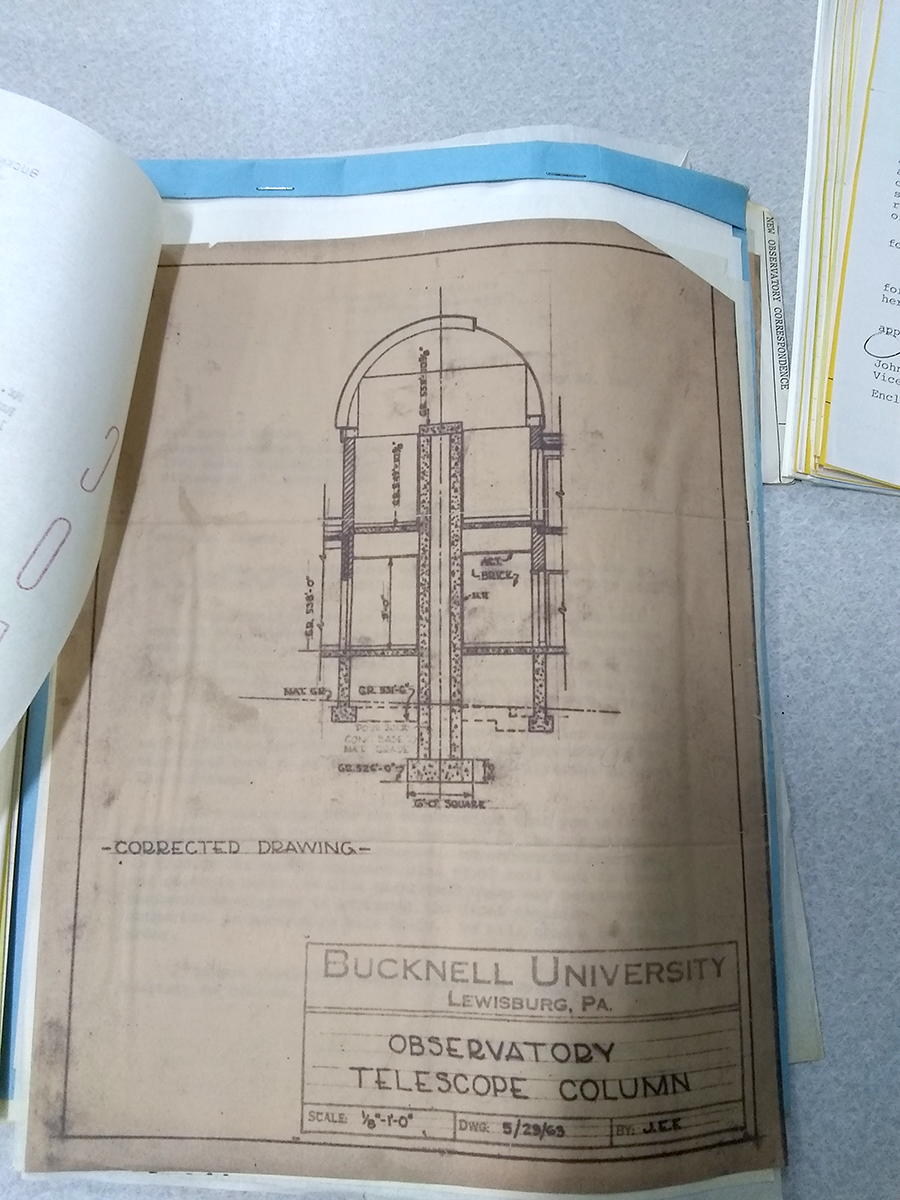

Our wonderful Clark refracting telescope support column, in all its masonry glory. Structurally isolated from the rest of the building so that footsteps don’t cause wobbles in the telescope’s field of view.

Sometimes, it’s the little things.

Discoveries in the Physics & Astronomy shop | Science, curiosities, and surprises

Our wonderful Clark refracting telescope support column, in all its masonry glory. Structurally isolated from the rest of the building so that footsteps don’t cause wobbles in the telescope’s field of view.

Sometimes, it’s the little things.

Do you ever set aside some papers, because you don’t need them right now, but they were maybe interesting for later? And then eventually there’s just a pile or folder or shelf devoted to these, because you’ve inadvertently started a collection? And then, half a century later, someone stumbles across these boxes and wonders, why?

Why do we have boxes of printed press releases from NASA in the early 1970s? Probably the same reason we have old math exams from the 1940s out at the Observatory. (That’s a post for another time!)

Honestly, if we’d been diligent about tidying this stuff, this blog would be way less interesting.

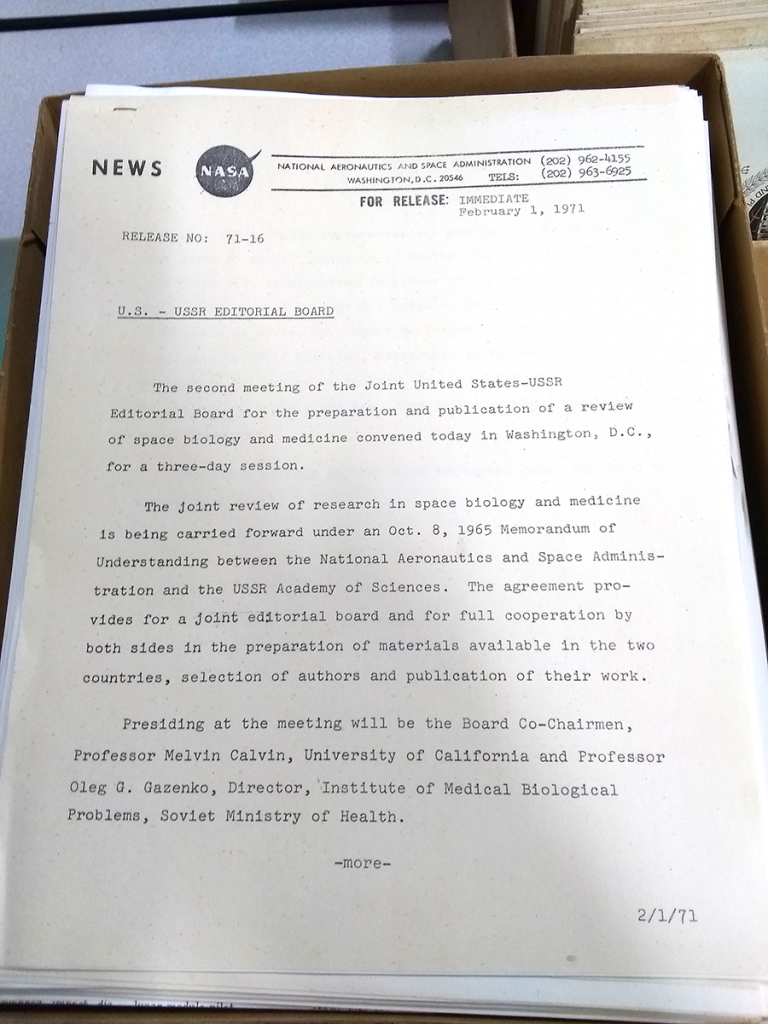

This was a quality instrument, we’re supposing. Currently it’s a steel door, with its associated cabinet, apparatus, and everything else unaccounted for and presumed long gone. Any details associated with it have disappeared as well.

But check out that sticker! The Nuclear-Chicago Corporation made a variety of devices for nuclear radiation detection, although a cursory internet search reveals mostly hand-held items rather than cabinet-mounted equipment. Still, have a look through that fantastic mid-century aesthetic! Back in the days when uranium prospecting was what all the cool kids were doing.

They put out the model 2586 “Cutie Pie” in 1954. The Cutie Pie.

At any rate, Abbott Laboratories bought them out in 1964, so whatever device this accompanied goes back to sometime between 1954 – the name change to Nuclear-Chicago – and the 1964 sale. Should we ever stumble across the remains of it, rest assured we’ll make note of it.

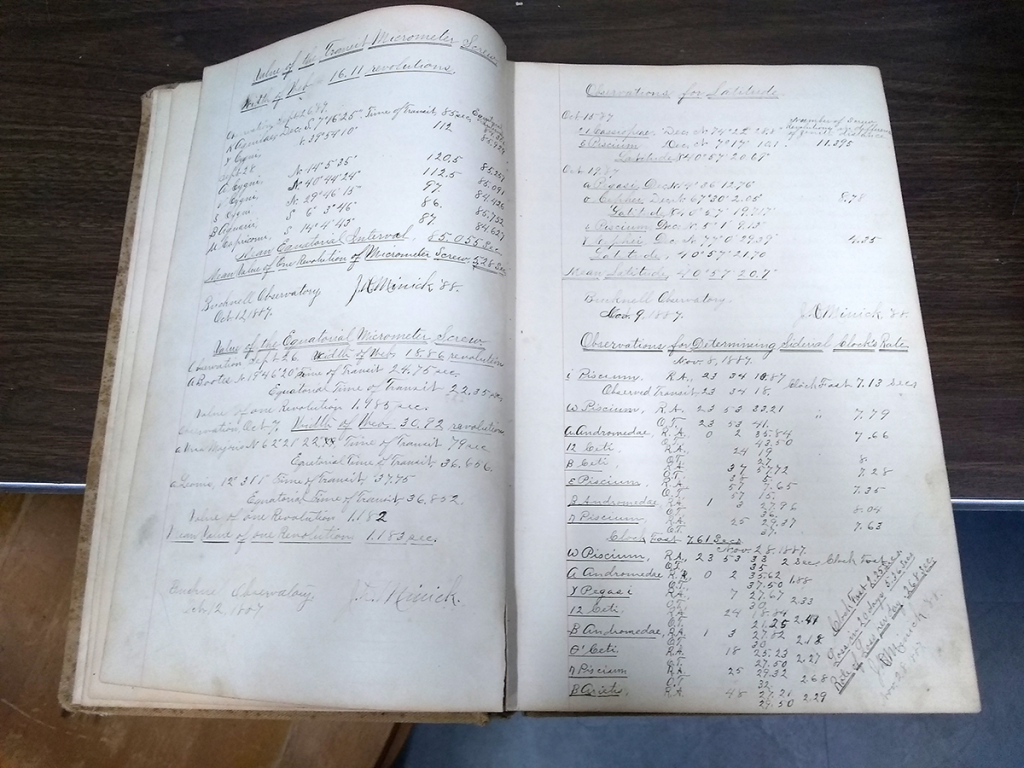

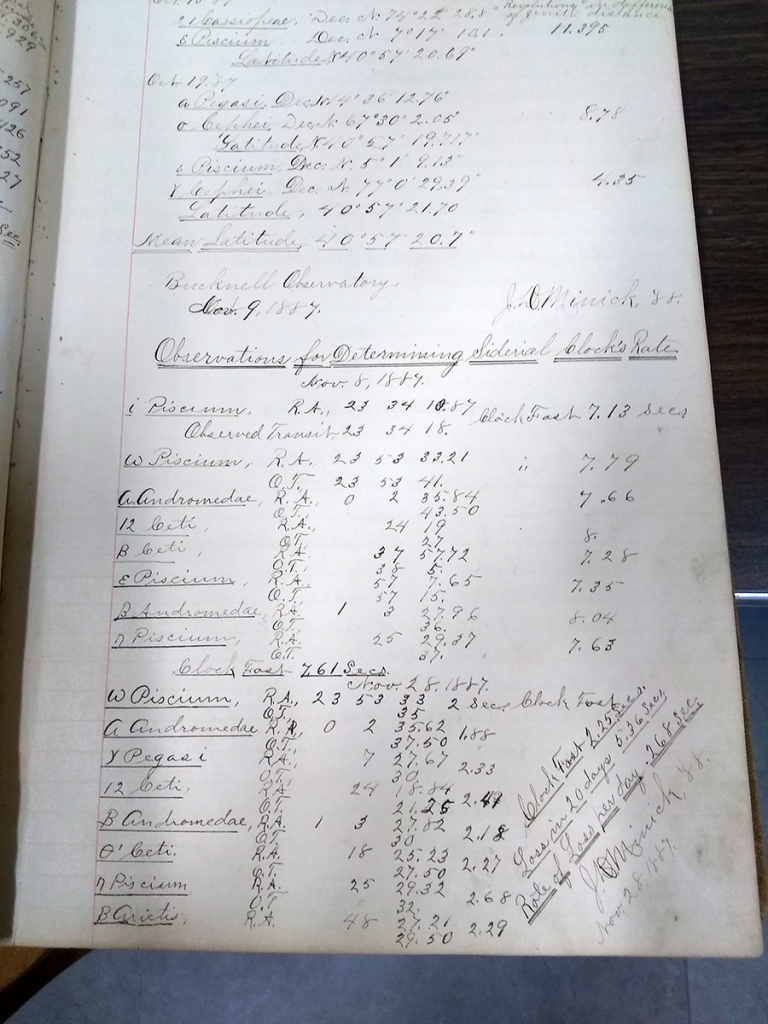

Some years ago, back in 1887, the University received a lovely Clark & Sons refracting telescope, complete with a clock drive to track the stars against the Earth’s rotation. When a shiny new toy scientific apparatus arrives on your doorstep, it’s very important to confirm that it works as intended. Here, in an old notebook, we see the original data on the clock drive’s variance from the ideal sidereal tracking rate.

“Observations for Determining Sidereal Clock’s Rate Nov. 8, 1889”

Then follows a table of stars with known right ascension and declination, then a repeated set of measurements 20 days later. “Rate of Loss per day .268 sec.” Considering the frequency with which proper polar alignment and tracking proves a nuisance more than a century later, that seems pretty good. The clock drive is long gone, of course, so we can only guess at how accurate it was and stayed throughout the decades.

It looks like these entries were by a J. D. Minick, Class of ’88. Best guess is a John David Minick, graduate of Bucknell in 1888, listed as Prof. John D. Minick of Lenoir, N.C. in the Memorials of Bucknell University, 1846 – 1896. Astronomer, apparently. Mathematician? Physicist? At this point, we’re content with the mystery.

Around the same time, Bucknell was also the home of one Jacob Henry Minick, Class of 1891. He’s listed in the link above as from Orrstown, PA, in Franklin County. Any relation?

His name lives on at the university in the form of an endowed scholarship:

“The Jacob H. Minick Fund was established by a bequest from Jacob H. Minick, Class of 1891, the income of which is to be given each year to students who, because of some physical difficulty, are forced to use crutches during all of their college work.”

There’s a story there, no doubt.

It’s a regular occurrence that we run across old objects which just aren’t useful anymore, at least not as they were originally intended. Sometimes they’re junk. Sometimes they work well enough, and it’s nice to have a backup around, just in case. And sometimes?

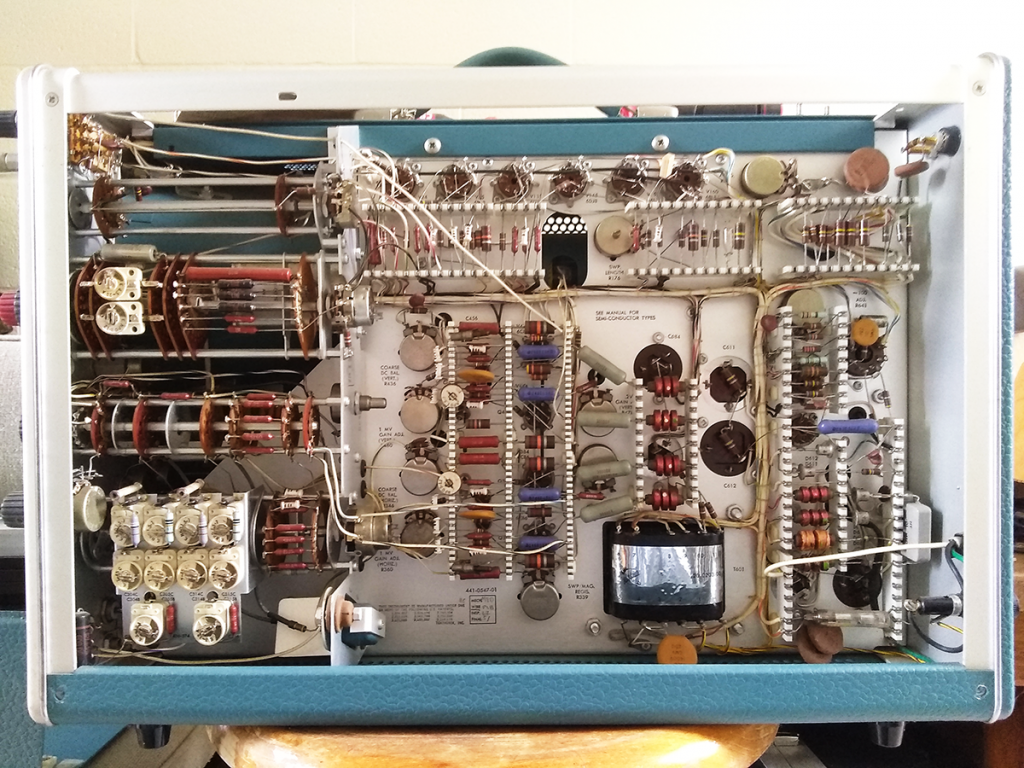

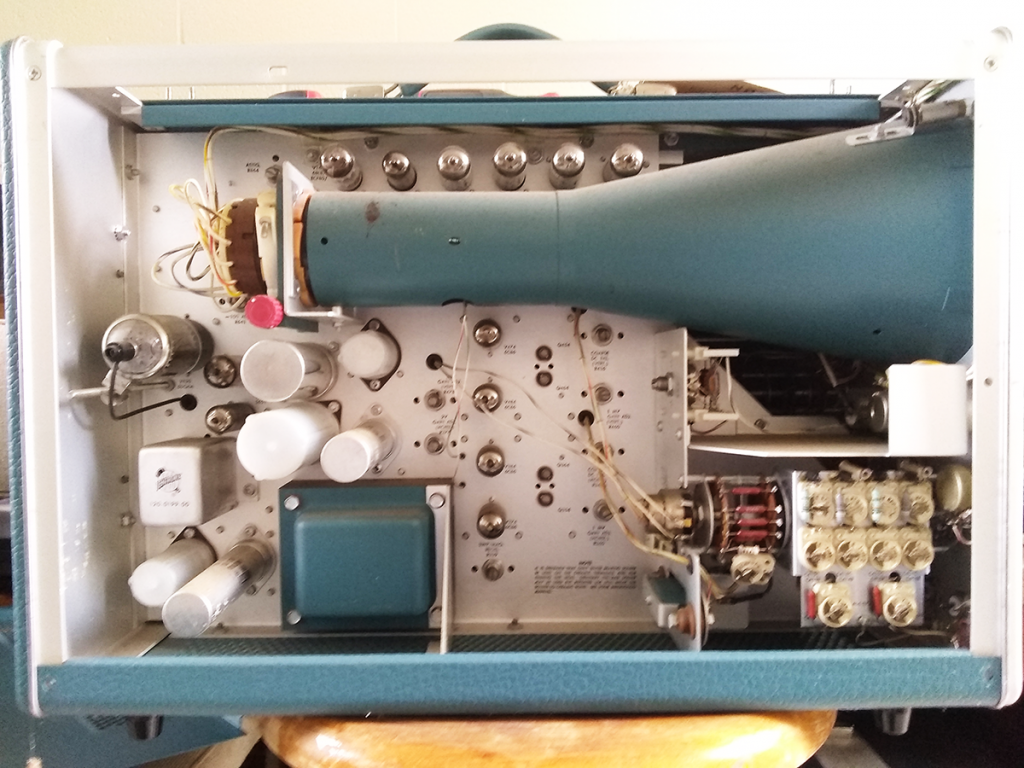

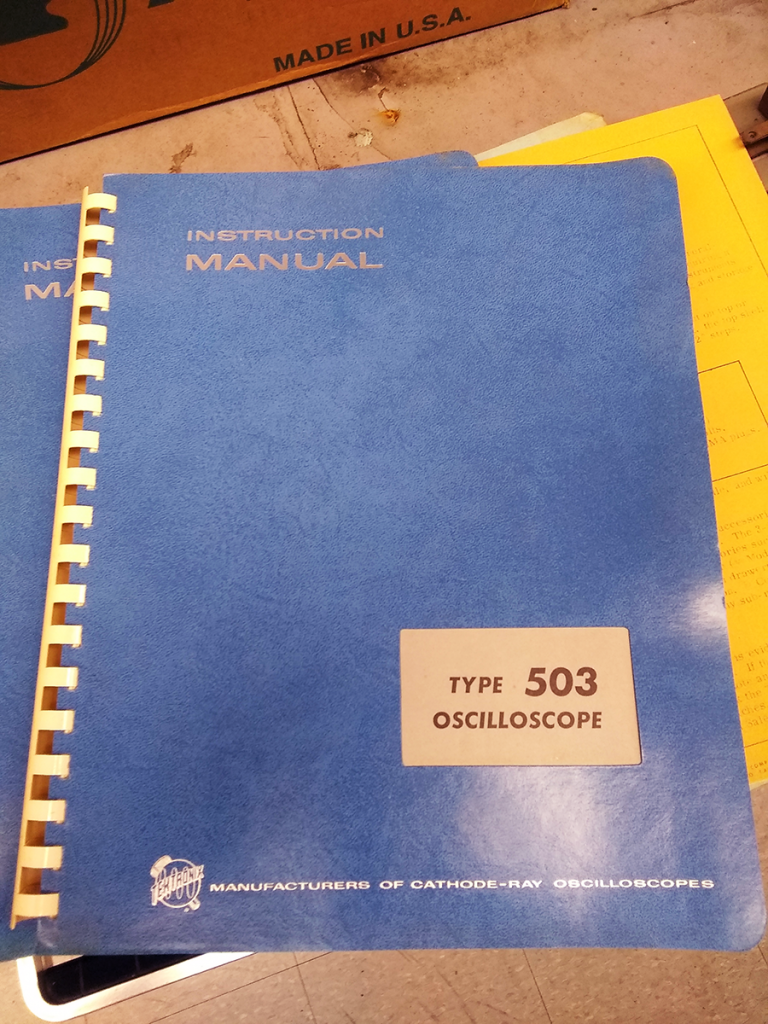

Sometimes it’s old enough that it’s got a little bit of cool going on. Like this 1960 Tektronix 503 oscilloscope. It shouts SPACE AGE! from all angles. (Our good friend Matt likened the round display screen to a porthole into a sea of electrons. Of course!)

It might not work anymore – probably depends on whether the capacitors are still in good shape – but we haven’t tried. It’s not like we’re going to use this in place of any of the other, more modern, higher-frequency, smaller-footprint ‘scopes we’ve got in numerous labs. This stays around because it looks amazing.

Even the insides are fantastic! Big honkin’ resistors, induction coils, capacitors, all widely spaced for effective heat dissipation. You can trace how each knob turns and switches circuit components in each of those cylindrical arrays. As a kid, this is probably the mental image of what it looks like inside a giant robot. Giant robots are the best robots.

On the other side, we can check out all of the vacuum tubes that made this sucker hum. Plus a big ol’ transformer and a wonderfully stylish CRT for the display. Vacuum tubes don’t show up many places anymore, having been replaced with miniaturized circuit components, but we still have use for them in special cases. (Photomultiplier tubes in our wave-particle duality lab, for example.) Despite their rarity, you can’t deny that they look awesome.

We even have a pair of manuals. A pair. Does that mean there were once a set of 503s around? Could we possibly stumble across another, gathering dust beneath a workbench in a dark corner someplace?

After all, that’s where this one popped up, undisturbed for decades. Never know what you’ll uncover.

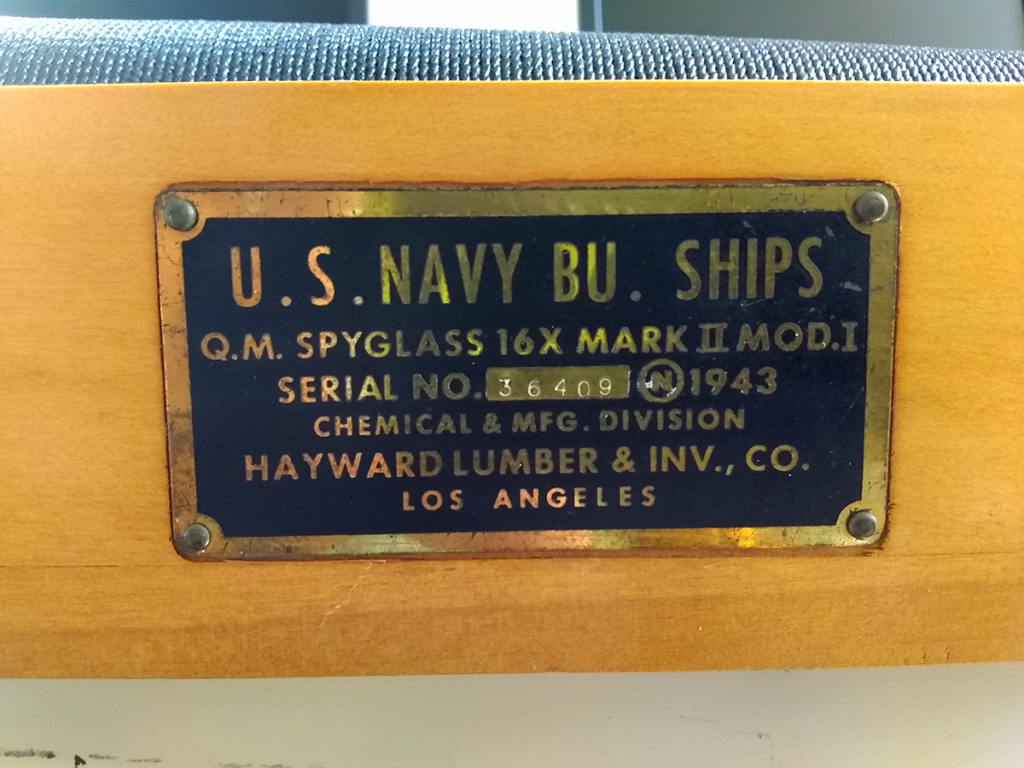

It’s not just telescopes at the Observatory. We also have a spyglass. What’s the difference?

There are a variety of potential optics for a telescope, using reflectors to reflect and focus light, using refractive lenses to bend and focus light, using mirrors to turn a beam around corners, using these in combination. Each has its pros and cons, and careful optical design and precise manufacturing work to gather lots of light, to provide good resolution and magnification, and to correct for optical aberrations.

And in doing all of that, the image reaching your eye or the camera sensor gets flipped upside down. Also in reverse, if you’ve got a mirror in your optical train. When looking at stars and deep sky objects, that’s not a big deal. “Up” is arbitrary in space. For terrestrial viewing, however, up matters. Seeing that incoming pirate ship upside down is disorienting. So a good spyglass keeps up as up.

It does so by using a Galilean refractor design, which has a concave lens in the optical assembly to avoid the upside-down flip. The resulting telescope is necessarily longer than a comparable refractor with convex lenses, and thus heavier. That weight tends to limit the possible objective aperture size, and the practical magnification limits are low. Still: very effective for spotting Edward Teach at a distance, or for identifying the four largest moons of Jupiter.

Binoculars, incidentally, manage to keep the world upright thanks to a set of prisms between the objective lenses and the eyepieces. Yet another handy trick in the optical design toolkit.

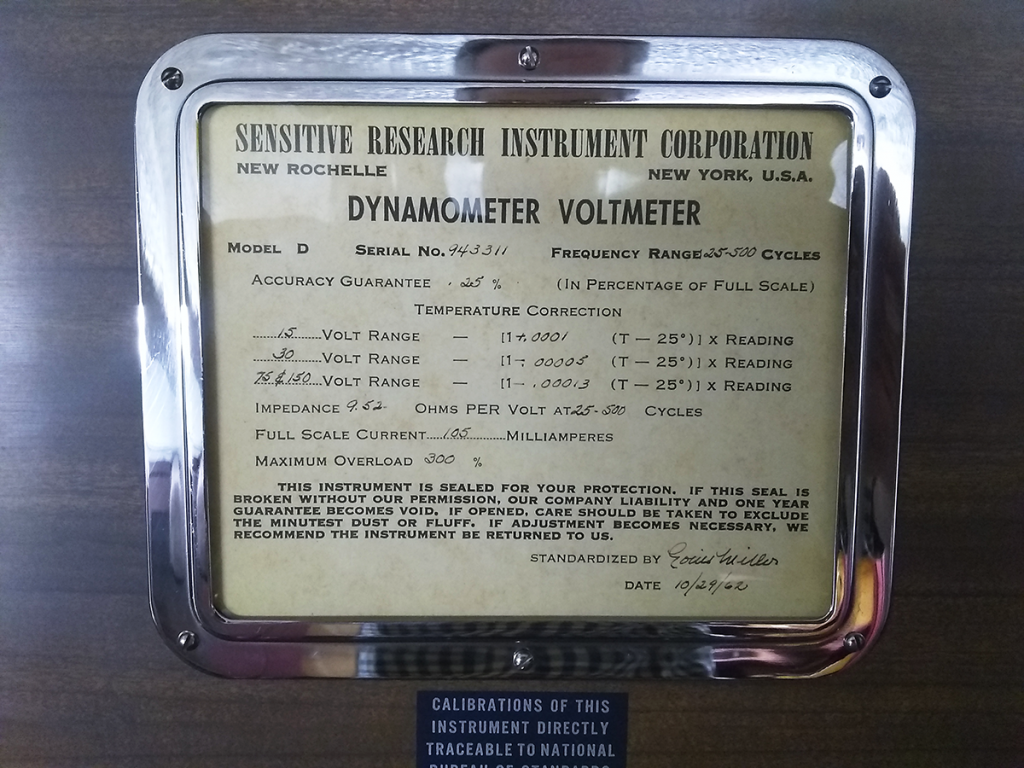

Sometimes you just have to love the directness of the manufacturers of scientific apparatus and equipment. “Sensitive Research Instrument Corporation” is not, by any standards, snappy. But it is clear about their product line.

An accuracy guarantee of 0.25%, standardized by Louis Miller on 10/29/62. Charmingly hand-written on this label affixed inside the case. (Sadly, no one marked this one with the price.)

Not presented entirely without comment, as it’s hard to contain the urge toward snark. Yes, we know what this is and why it’s useful; yes, we know what they mean by “gender” and how F/F looks the same but changes things. Yes, yes.

At any rate: the cables which once needed this adapter are gone, as is the equipment it carried electronic messages to and from. Now we just have a block of metal and plastic and the opportunity to squint and say, “I’m not sure that’s how that’s supposed to work.”

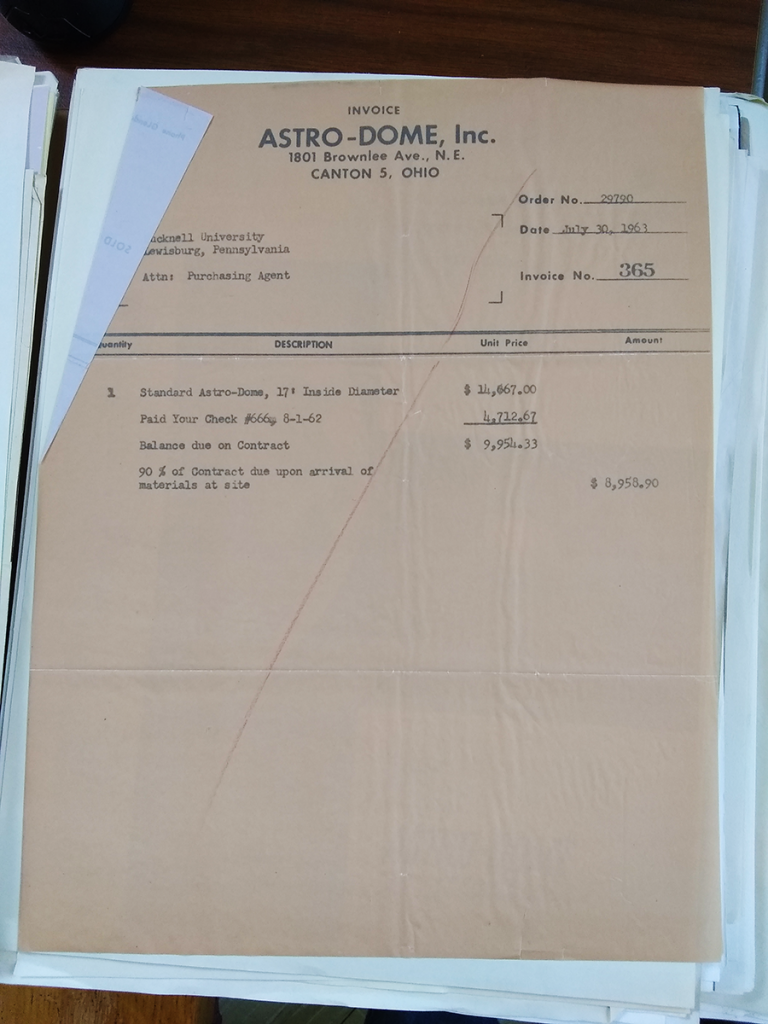

In 1963, one could purchase a Standard Astro-Dome with a 17′ inside diameter for the low, low price of $14,667. It must have been a worthwhile investment, because we’re still using it 60+ years later with no plans to update or replace it anytime soon.

Adjusted cost in 2023 dollars: $144,932.41.

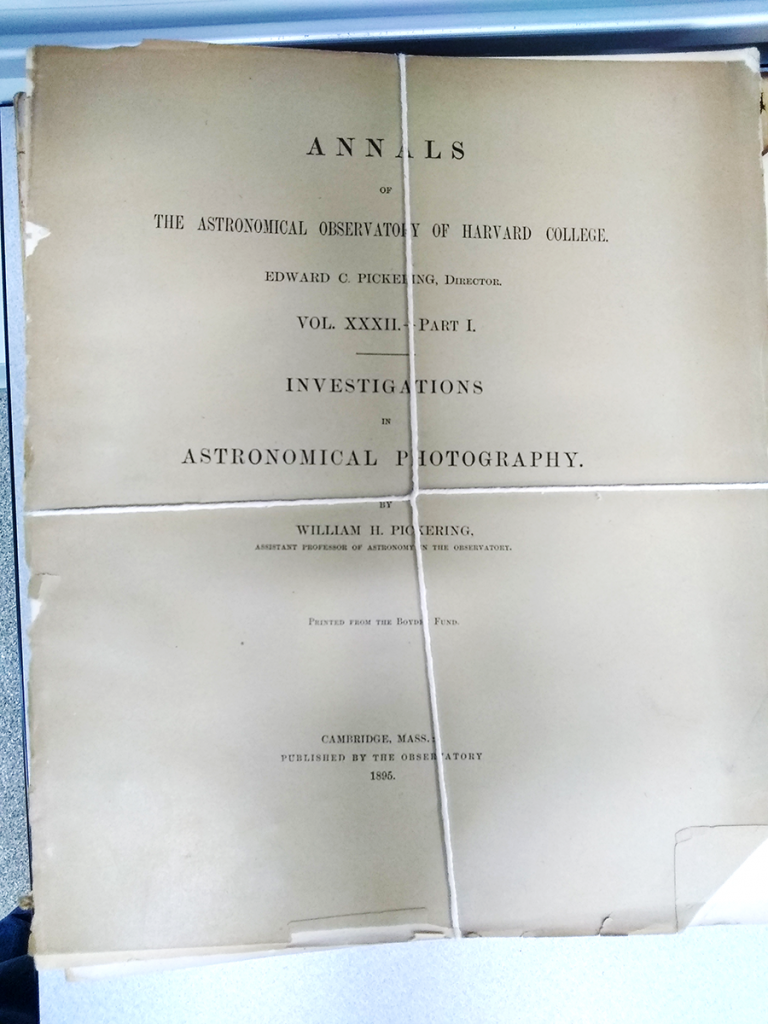

Among the stacks and stacks of old records and books at the Observatory, we have a substantial text discussing best practices for astrophotography from…

1895. Sweet.

You may read a scanned version online if so inclined. Fun to note that, broadly speaking, the difficulties remain. With every improvement in technology comes an increased ability to explore and a growing expectation of quality, so there’s always opportunity to do better. From page 2:

“In order to appreciate the accuracy with which the mechanical adjustments

must be made, and the care with which they must be used, we should recollect

that in a telescope of sixteen feet focal length, a second of arc is rather less than

.001 of an inch, — a quantity quite invisible to the naked eye. We are required,

therefore, to keep a mass of metal weighing several hundred pounds following the

star with such accuracy, for perhaps an hour, that it shall not for any length of time

shift to one side of the other from its true position by this amount.“