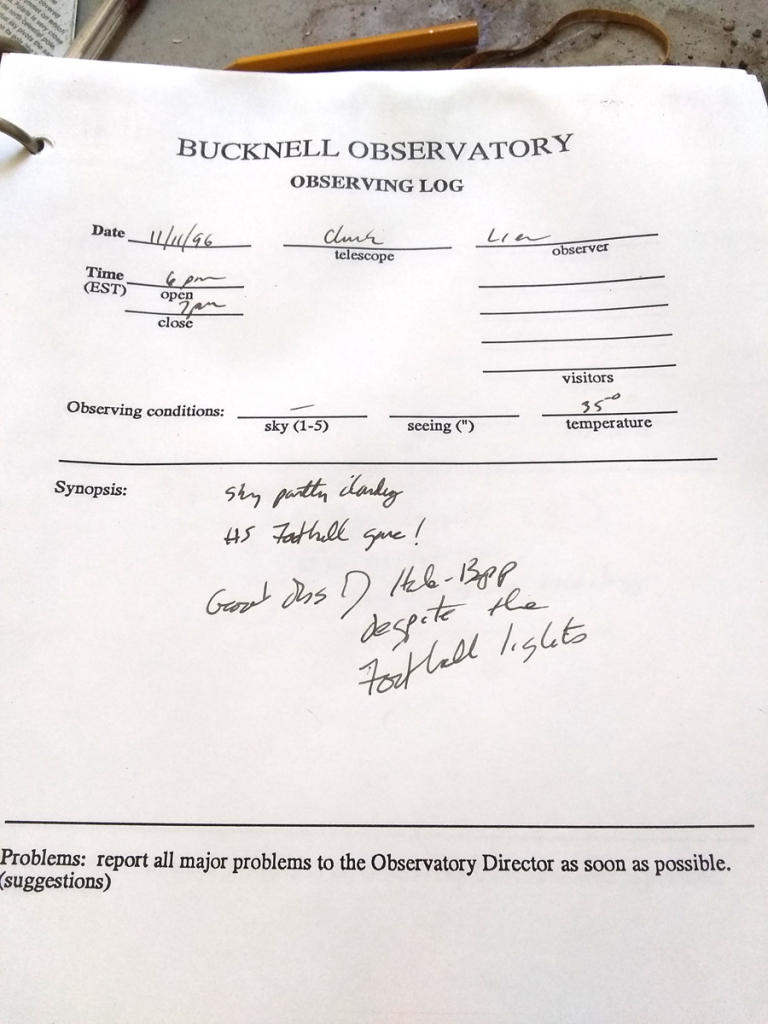

In cleaning out the Observatory, there are endless collections of observing notes from years past. Each a sheet, filled out by hand, with brief remarks on what was observed, the group in attendance, and anything else that seemed salient at the time.

Here, one of many sheets during the long period – about a year and a half – when comet Hale-Bopp could be seen in the sky. Of particular note, and still an issue for Observatory use today:

“Good obs of Hale-Bopp despite the Football lights”

Yup. More than a quarter-century later, and still the same issue with the football lights.